Increasingly, local gardeners say they’re raising plants they couldn’t as little as 10 or 15 years ago. “I’m finding I can grow some Mediterranean crops — artichokes, lavender, okra — with ease now,” notes Asheville gardener Nan Chase, the author of Eat Your Yard!

That may be a treat for passionate backyard growers, but it also throws a spotlight on a hotly debated topic in plant circles: zone creep.

Lending urgency to the discussion is the pending release of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s new Plant Hardiness Zone Map, due out later this year. A useful tool for professional plant growers, retailers and weekend gardeners alike, it helps you know if that pretty plant you're eyeing (not to mention long-term items such as trees and shrubs) has a good chance of surviving the winter and showing up for spring.

The current map, dating back to 1990, recognizes 11 zones in the U.S. and Canada, each representing a difference in the average minimum temperature of 10 degrees Fahrenheit. These geographically defined areas are split into subzones A and B, denoting 5-degree increments.

Most of Asheville and environs, for example, has been classified 6a or 6b. Plants in 6a can withstand temperatures down to -10 F; in 6b, the limit is -5 F. Now, however, many local gardeners and growers consider Western North Carolina to be in zone 7a. This phenomenon is known as “zone creep.”

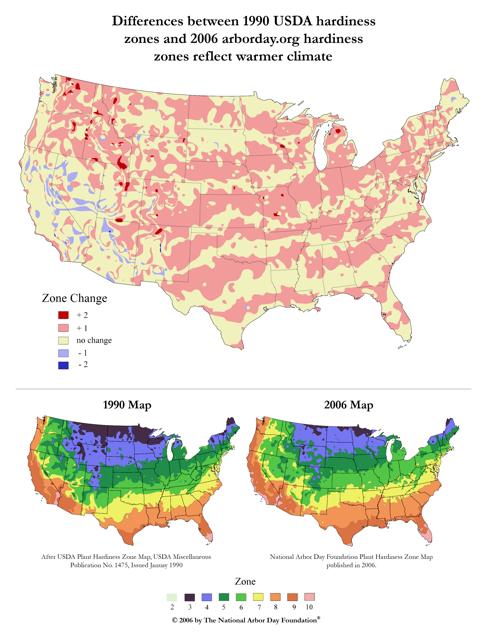

The new map will boast many fancy features likely to intrigue professional growers and weekend gardeners alike, but for many people, the most important question is whether it will reflect zone creep. A 2006 map produced by the Arbor Day Foundation shows many areas across the country one whole zone warmer than before. Many gardeners use it as a stopgap till the official USDA map becomes available.

But you don’t have to like getting your hands in the dirt to be affected by this phenomenon.

To begin with, some plant species aren’t likely to survive. As temperatures rise and zones creep upward, plants follow, notes Joe-Ann McCoy, director of The North Carolina Arboretum’s Germplasm Repository. But sensitive ecosystems such as spruce/fir forests literally have nowhere to go. "In the last three ice ages," she explains, "our mountains weren’t glaciated, and everything was pushed to its limit." Other species such as Gray's lily, a beautiful wildflower found in only a few counties in northwestern North Carolina, may also be at risk.

Meanwhile, invasive species that like thrive in temperatures could pose huge problems, and non-natives might produce more seed. These threats change the very face of conservation. Instead of leaving plants in their natural habitat in hopes of re-establishing threatened populations, conservationists are now increasingly shifting their focus to collecting and storing seeds, in hopes of preserving native species for future re-introduction. Collected seeds are typically viable for 50 to 60 years.

The Forest Service, too, is looking ahead as far as 2050 or even 2100 to prepare for worst-case climate scenarios. The federal agency believes “the effects of changing climate — specifically, severe weather events and drought in our area — will have an effect on forest structure, especially combined with current insect threats, disease, invasives and wildfire,” notes Zoë Hoyle, a science writer and editor at the Southern Research Station. “But the Forest Service,” she continues, creates its own maps, “using more climatic variables than just temperature.”

Meanwhile, what’s holding up the USDA map at this point is not the actual mapping work but the delivery system, Kim Kaplan of the agency’s Agricultural Research Service explains. “The final part of the process is finding a server to host the digital map and the number of users it will have." That might sound simple, but with the data-intensive product expected to attract a whole lot of users, finding an adequate server could take six months or more, perhaps pushing the release date into 2012.

Kaplan says that while the new map will reflect some zone creep, the changes may not as significant as some expect. The map, she explains, incorporates hot and cold “habitat islands” and more accurately depicts zone borders, where elevation, slope, wind and bodies of water all affect temperature fluctuations.

The map, however, is based not on long-term climate projections but on weather data — specifically, the coldest average annual temperatures in different areas over the last 30 years, according to National Weather Service. That time span falls far short of the 100 years most climatologists say provides a better basis for assessing climate shifts.

But since that perennial you're buying will probably live about 10 years, and the most important factor for gardeners is knowing their own yard, the USDA felt 30 years strikes a good balance.

So while horticulturalists continue to debate zone creep, for gardeners who are forever chasing the holy grail of plants, this news may not be all bad — at least for now.

— Cinthia Milner gardens in Leicester.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.