Never underestimate what a few talented women can do.

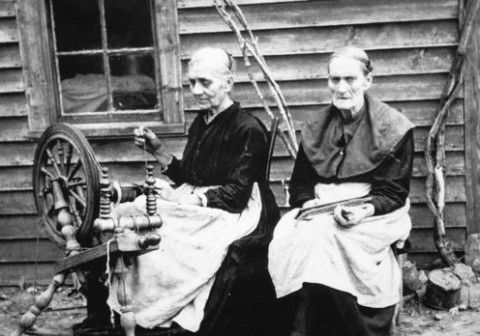

“Frances Goodrich was the one who started it off,” says Les Reker, director of Mars Hill University’s Rural Life Museum. “She was a missionary from New York, and she came down here to, you know, do what missionaries do,” continues Reker, indicating a black-and-white photo of a spindly, sharp-eyed woman.

“But she discovered that the area had this tradition of weaving, and she teamed up with a few of the ladies to create Allanstand Cottage Industries. It was designed to give women their independence, really: It provided industry to the region and money to the women, and pretty soon this little cottage industry was gaining nationwide acclaim.”

Reker, a walking encyclopedia of history and folklore whose career has spanned locales as far apart as Texas and Pennsylvania, is providing a guided tour of “Interwoven: Coverlets, Ballads, and America’s Discovery of Madison County Folklife,” the museum’s first exhibition since its grand reopening last Sept. 28. The modest space is housed in Montague Hall, a squat, fortresslike stone structure.

Constructed in 1918, Montague Hall is one of the oldest buildings on campus. “It was built as the college’s library,” Reker explains. “The Montagues provided the funding, but the community believed so deeply that the college should have a library that they brought the stones themselves.”

Reker and his staff (“three full-timers, a few work-study students and one intern”) have clearly taken pains to maximize the use of the limited space. On the right is a replica half-cabin, complete with roof, fireplace and flooring. In the center of the floor sits a large, ornate, fully functional loom. The exhibit explores the intricate history of craft in Madison County and the rest of Western North Carolina; weaving and cloth work played a key role in bringing national attention to the area.

Asked how much cloth such a loom could produce, Reker says, “Several of the students have been working on this; I’d say we can get about 8 inches per day.”

A small, black radio in the corner plays a soothing tune that crackles in the unmistakable manner of old recordings. I learn later that the singer is Emma Hensley Shelton. Her mother, Rose Hensley, was one of the Allanstand Cottage Industries weavers, whose melodious singing voices and fondness for ballads are the exhibit’s second focus.

“This gentleman, Cecil Sharp, came to the mountains and discovered that all of these women sang while they were weaving, and they sang very well, and they were singing old English ballads,” Reker explains, pointing to another photo high up on on one of the exhibit’s large display boards. “The ladies called them love songs, but they came from England. And Sharp was amazed, because the way these women sang them was the purest form of the song he’d ever heard, including in the British Isles. That’s where ‘Interwoven’ comes from: this interplay between the weaving and the song.”

The recording in the loom house — one of only a few in existence of a Madison County native singing these ballads — is “quite a big deal,” says Reker. The copy came from the Library of Congress.

The thick, blue-gray display boards, maybe 10 to 12 feet high, convey most of the exhibit’s information. “Maintenance built these for us,” Reker reveals, adding, “Takes about four guys to move them.” Spread throughout the premises, they’re covered with black-and-white photographs: a woman dying cloth; a group of women in stifling, full-body dresses. A particularly memorable photo shows an older lady looking mischievously at the camera as she plays an accordion.

Scattered among the displays are original artifacts pertaining to the history of weaving and fabric craft, including a number of specialized spinning wheels. One, for example, was used to spin linen. “Linen is made from flax,” notes Reker, “and flax is very brittle. You have to keep it wet the whole time, and there’s a contraption on this spinning wheel that allows for that.”

A few of the displays feature pictures of the various plants used to create cloth and dyes. A bundle of actual flax does indeed look very brittle, and a kids table in the corner, covered with scraps of bright construction paper, explains how to make a paper weave. “That’s all there is to it,” says Reker, gesturing toward a couple of completed ones on display. “With construction paper or with cloth, it’s the same basic principle.”

Then and now

Montague Hall served many functions over the years, even housing a radio station before the original Rural Life Museum was established there in the 1970s.

“It wasn’t really open to the public then,” notes Reker. “Tours were by appointment only.”

Things continued that way for the next three decades. But by 2006, the former library building was seriously decrepit, and the school had to shut it down. The biggest problem was that ancient enemy of all preservationists and historical artifacts: water damage. Museums must maintain very specific atmospheric conditions, including temperature and humidity, and the aging structure wasn’t suitable for that. The restoration process would take nearly seven years, but after significant investment by the school, abundant community support and a couple of grants, the renovated space finally reopened last September. “Interwoven” was a logical first exhibit, considering its subject’s rich history, importance to the region and deep connection to the locals: Many of the families who produced work through Allanstand are still in Madison County today.

“People don’t realize what this little weaving industry grew into,” says Reker. “Frances Goodrich stepped aside in 1930, and afterward the Allanstand Cottage Industries became what’s now the Southern Highland Craft Guild. It brought a lot of attention and rediscovery of craft to the region. I mean, this gained national recognition. A couple of members, the Walker sisters, decorated a room in Woodrow Wilson’s White House. It’s been redesigned since then, but I wouldn’t be surprised if some of those hangings are still there.”

An enduring legacy

The legacy of Goodrich’s work with Allanstand Cottage Industries is still felt strongly today through the Southern Highland Craft Guild, a major presence in the region.

“The guild is a member-run organization,” Public Relations Officer April Nance explains. “We have 930 members throughout nine states, although there is a concentration around Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee.” The group’s mission is “bringing together the crafts and craftspeople of the Southern Highlands for the benefit of shared resources, education, marketing and conservation.”

In keeping with the standards first established by Goodrich, becoming a guild member isn’t easy. Applicants first submit photographs of their work to a jury of guild members; if the jurors find the items to be sufficiently high-quality, they invite the artisan to come in person and bring the pieces for close examination.

“Guild membership is very advantageous, says Nance. “It allows members to sell in all of our shops and craft fairs, including our semiannual Craft Fair of the Southern Highlands that we put on at the U.S. Cellular Center.”

The guild buys members’ work outright and then sells it in six retail outlets, including the Allanstand Craft Shop at the Folk Art Center. Located at milepost 382 on the Blue Ridge Parkway, the center also serves as archive, gallery, museum and headquarters for the organization. But the range of crafts on offer has evolved significantly since Goodrich’s day. The Allanstand store, for example, now sells such wide-ranging artifacts as handmade cutlery, furniture, jewelry, leather-bound journals, wooden toys, metalwork, jewelry boxes, wooden cowboy hats (you read that right) and ornate beeswax candleholders that somehow don’t melt when put to use.

Despite the flood of cheaper, mass-produced products, handmade craft remains a good, if not booming, business. “Oh, I’d say on a busy day in October we’ll do about $10,000 in business,” Nance estimates. “People respond to things that are useful and beautiful, and we’ve really seen a shift away from mass-produced items: 250,000 people come through our stores per year. I think people just want items of enduring quality. Asheville has this thing about going local — well, we’ve been promoting local since 1930.”

“All the attention this area gets for its fine crafts, from furniture to brooms to folk art, started with this cottage industry,” stresses Reker.

With a quarter-million people shopping local for local crafts in the area, it’s no surprise that interest in the history is high. In the first couple of months after the reopening, the Rural Life Museum saw upward of 2,000 people come through its doors. Since then, it’s averaged several hundred a month. Many groups from schools, senior centers and the university’s own classes have come out to view the pieces and take tours. Reker says he hopes to average 8,000 to 12,000 visitors per year.

Full circle

“This is the coolest thing,” says Reker, indicating an elaborate wooden device that looks like a Ferris wheel crossed with a birdhouse. “This is called a spinner’s weasel. They used these to wind up their yarn into a bundle called a skein,” he explains. “You turn it 40 revolutions and you would have one skein, which equals about 80 yards. Well, there’s a little mechanism inside here that makes a noise once you finish those 40 revolutions, so after you had a skein, the weasel “popped”: Pop goes the weasel. That’s where we get the nursery rhyme. Which is also an English ballad, to bring everything full circle.”

Reker expects this to be the last stop in his peripatetic career: “Oh, I’m not moving again,” he declares. “I bought a farm in Alexander, and we’re staying put.” Reker’s family visited the area several times when he was a child, and his daughter attended Warren Wilson. “I just fell in love with the culture and the history. North Carolina is the best place I’ve ever lived: Great landscapes, great people.”

Meanwhile, Reker and his staff are committed to making the museum — the only one in Madison County — the best it can be. To that end, they’re carefully planning for future exhibits.

“Those are pieces from another collection we’re gathering,” says Reker in response to a query about a small loft section in the back of the building. “The downstairs is not quite ready yet, but we’re working on it.”

In addition, the museum is designed to be easily reconfigured to accommodate new exhibits (though the four maintenance people needed to move a single display board might take issue with the word “easily”). “Interwoven” will be on display until this fall, after which the museum will focus on a different aspect of the county’s rich history. Plans call for two exhibits per year, and Reker says he has plenty of ideas. “We have a great relationship with the Eastern Band of the Cherokee,” he reveals. “There’s the history of African-Americans in this area. We’ve got an idea about the train system and how much that changed the region. I mean, the thing that brought the Vanderbilts to the mountains was the train system, and look how much that changed Asheville.”

Museums, he continues, “tell stories about people using objects. Above all, I hope this will allow people to recognize the value of mountain history and to tell the story of Western North Carolina: both the rural life of the region and the lives of the great mix of people who worked to carve out their lives here.”

Freelance writer Cameron Huntley can be reached at cameron.huntley1@gmail.com.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.