On Oct. 23, 1929, the Western North Carolina Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal church was held in High Point. Temperance, world peace and race relations were among the topics discussed. A report on the latter provided a number of recommendations to improve the relations between Black and white citizens, including a proposal to include sermons on race.

Over the next four decades, Race Relations Sunday became an annual event in Asheville. The local paper often previewed the gatherings, listing the names of presenters and the event’s themes, including: “Why Not Try Brotherhood?” (1947); “Of One Blood” (1952); “That All May Be One” (1953); and “Christ’s Challenge — the Church with the Open Door” (1956).

Scarcely did the paper provide excerpts from these sermons. But on Feb. 10, 1941, The Asheville Citizen included the Rev. C. Grier Davis’ address to the First Presbyterian Church. In it, Davis, who was white, shared a passage from African American author and educator Robert Russa Moton’s 1929 book, What the Negro Thinks. The passage declares:

“Perhaps no single phrase has been more frequently used in discussing the race problem in American than the familiar declaration, ‘I know the Negro.’ It has been commonly employed to support opinions and sustain the convictions of large numbers of white men and women who are zealous to defend existing customs and practices which give to the Negro a different status in civic life from that occupied by his white neighbor.”

After reading the section aloud, Davis asked his congregation if Moton’s observations surprised them. He then further challenged the church with his own thoughts on the matter, stating:

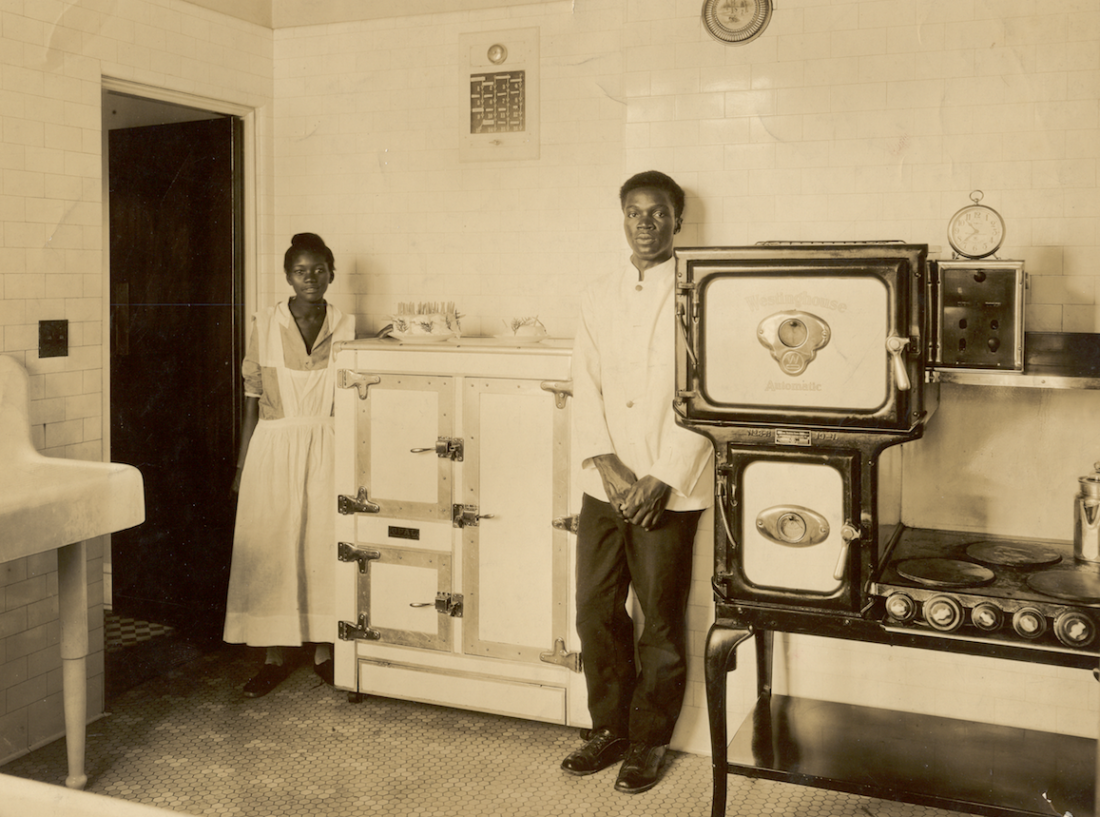

“[T]hink for a moment of how little you know about what the negro thinks and how he feels. Few of us ever talk to him as man to man. Our intercourse is always on the basis of servant to master, of sexton to church officers, of employer to employee. We rarely read a negro newspaper or literature which portrays the life of the negro. On the other hand the negro does understand the white man. And the way he sees us is not all to our credit. In the public schools the negro children study the social and economic life of the white man. In the movies and over the radio they are further educated about the white man. In addition to all this the negro servants are the silent observers of our conflict and habits in the most intimate relationships of our homes.

“When anyone dared to suggest that we need to understand the negro better, we have traditionally become emotional about the question and have dismissed it with a shrug saying: ‘I understand the negro all right. Let him stay in his place and all will be well.’ Well, are you quite sure about that? You may understand the uneducated negro of ante-bellum days who always calls you ‘boss,’ but do you understand the negro of 1941, the thousands of negroes who have graduated from high school and college, whose tastes for a better way of life have been cultivated, and who in all sincerity seek only for an opportunity to live a useful life among his fellows. Do you understand that negro? Have you ever sat where he sits?”

But Grier’s zeal for racial justice doesn’t appear to have extended beyond his Race Relations Sunday sermon. Or at least coverage of his efforts do not show up in subsequent searches.

By 1960, this lack of sustained interest in improving race relations beyond the annual gathering became a point of criticism directed at the churches. In a Feb. 13 editorial, The Asheville Citizen wrote, “Generally, Race Relations Sunday is not a strong influence for better communication between whites and Negroes. It is clear enough that the patterns of racial separation in the sphere of religion will be back in force on Monday.”

Despite the critique, some local churches continued participating in the yearly event throughout the 1960s. On Feb. 11, 1963, The Asheville Citizen included a brief excerpt from the Rev. James A. Cannon’s sermon at Central Methodist Church. The guest speaker declared, “As Christians, we must repent; we must see all people as human beings; we must insist on one moral code; and we must love one another.”

Thanks to Mr. Calder for continuing to enlighten us about Asheville’s history.