It all started with a brawl.

Following two road games against the Winston-Salem Icehawks, the Asheville Smoke minor league hockey team played its inaugural home opener on Oct. 21, 1998, at the Asheville Civic Center (now the Harrah’s Cherokee Center – Asheville) against the Quad City Mallards.

Ron Wagner, then sports editor for the Hendersonville Times-News, was there covering the game. And like him, most attendees in the packed arena didn’t know much about the sport — beyond it being famous for spectacular fights between players.

“I think [the Smoke] knew that, and they wanted to give the people their money’s worth quickly. Because literally seconds into the dropping of the puck, every player on both teams squared off and started fighting,” Wagner says.

“There was no reason for it. The game was 10 seconds in, and it was a brawl all over the ice, and fans were going nuts. It was exactly what people paid to see, and they gave it to them. And I think it hooked people for a whole season.”

Such aggressive athletic entertainment remained in Asheville until 2002, when dwindling attendance and rising costs forced the team to fold. Over 20 years later, Xpress spoke with a few people involved with the team at different levels about the Smoke’s brief but memorable run and whether Asheville might support pro hockey anytime soon.

Lacing up

Based in Brantford, Ontario, the Brantford Smoke joined the United Hockey League in 1991. During the 1997-98 season, team owner Roger Davis asked a group led by Dan Wilhelm, co-owner of league rival Madison Monsters, to help him run the organization.

“When we got there, we discovered it was not a good market for the minor league team to succeed,” says Wilhelm, who left the Monsters and soon worked out a deal to buy the Smoke. “With the help of the league, we started looking at other markets and locations. And Asheville was one that came up as a highly desirable place to be, based on the population demographics and a number of different things.”

UHL representatives initiated talks with City of Asheville officials, and the interest in bringing the team to town was mutual. In 1998, the Smoke moved south, and Keith Gretzky — brother of hockey legend Wayne Gretzky — was hired as the team’s coach.

MaryHelen Letterle was one of many locals elated by the news. The Asheville native started playing inline hockey at age 13 and, when she was old enough to drive, played pickup ice hockey at rinks in Spruce Pine and in Greenville, S.C.

“I loved ice hockey — absolutely loved it,” Letterle says. “I was 16 when [the Smoke] came to town. They were looking for volunteers [to work at games], and I immediately signed up.”

Letterle was one of many locals who sold promotional items and gradually worked her way up the ranks to keeping statistics and helping run other game components, such as monitoring the penalty box.

Attendance averaged 3,362 during the Smoke’s first year. Players such as enforcer Kris Shultz quickly became fan favorites and chants of “Let’s go Smoke!” resounded throughout the Civic Center. The team finished second in the Eastern Division with a 36-35-3 record and made the playoffs but were swept 4-0 by eventual league runner-up Quad City Mallards.

Building momentum

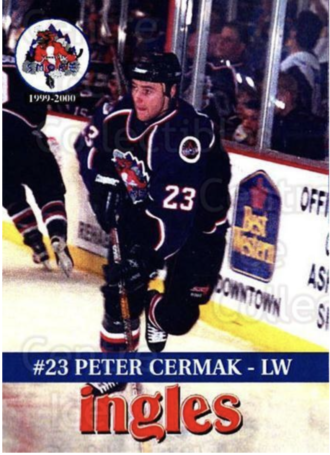

The following season, Slovakia-born Peter Cermak was traded to the Smoke from the Fort Wayne Komets and put up some of the best statistics of his 11-year career. In 42 games with the Smoke, the left wing scored 31 goals and tallied 33 assists. Gretzky’s brother, Brent, the Smoke captain and the team’s scoring (36) and assist (91) leader, was awarded the United Hockey League’s Player of the Year. The team went 34-38-2 but still made the playoffs, only to lose 2-0 to Fort Wayne, which made it to the semifinals.

“It was fun — I mean, you get to play a game,” says Cermak, who’s lived in the Asheville area for nearly 20 years. “So the schedule is really not that crazy. You practice early in the morning, and then guys go golfing or just hang out or take a nap. Other than that, there was a lot of traveling because in that league, you don’t fly anywhere. Everything’s bus.”

Winston-Salem was the closest opponent, with other UHL teams based in New York, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan and Ontario, Canada. In 1999, the Winston-Salem team moved to New York, but the Madison Monsters — then owned by Wilhelm’s brother Andrew; Dan pivoted to part-owner — relocated from Wisconsin to Knoxville, Tenn., to become the Knoxville Speed.

“It was nice when you just had a little over an hour bus ride and could have that rivalry,” Dan Wilhelm says. “And it was good for the fans, too, because they could travel as well.”

Enhancing that loyalty was how Smoke players quickly ingrained themselves in the community. Wilhelm recalls the athletes participating in youth birthday parties and interacting with fans at various events around town.

The Civic Center offered a distinctive atmosphere as well. Opened in 1974, the arena was designed for conventions, concerts, family show productions and sports — albeit primarily basketball.

Wilhelm recalls having to “squeeze the rink in the footprint” of the arena in order to still have good site lines from the balcony seats. (“Regulation ice is 200 feet by 85 feet,” he says. “I believe [the] Smoke ice sheet was 190 feet by 85 feet.”) But he notes that the conditions “brought the fans in closer to the action and made for a good environment for the players.”

Cermac agrees that the more intimate setting yielded enjoyable hockey and gave the Smoke an edge because other teams weren’t accustomed to such tight quarters. He adds that coach Gretzky devised plays to take advantage of the confines, including bouncing the puck off certain spots on the backboard where Smoke players, better aware of the distance, could get to the puck faster than their opponents.

But Cermac notes that the venue “could have used a little bit of work back then.” A refrigeration malfunction scuttled the team’s home opener in October 1999, and a month later, a game had to be canceled after the lights went out after the first period and two hours of effort couldn’t fix the electrical problem.

On the brink

Keith Gretzky resigned in May 2000, citing the Civic Center’s issues as one reason for his departure but otherwise praised his time in Asheville as well as the community. Brent Gretzky was traded to the Port Huron Border Cats, and Cermak went to the Cape Fear Fire Antz, leaving neither around for one of the Smoke’s most infamous games.

On Jan. 28, 2001, the team played the third of three consecutive nights against the rival Speed, which saw the teams alternate games between Asheville and Knoxville and then Asheville again. Letterle recalls tensions being high between the two teams and quickly escalating.

“The refs lost control of the game, and you just watched them domino — fights started, and then all of a sudden players started jumping off the bench,” Letterle says. “By the end of it, there were several teeth on the ice, and I think somebody attempted to use a skate as a weapon. It was ugly, but it was also incredibly memorable.”

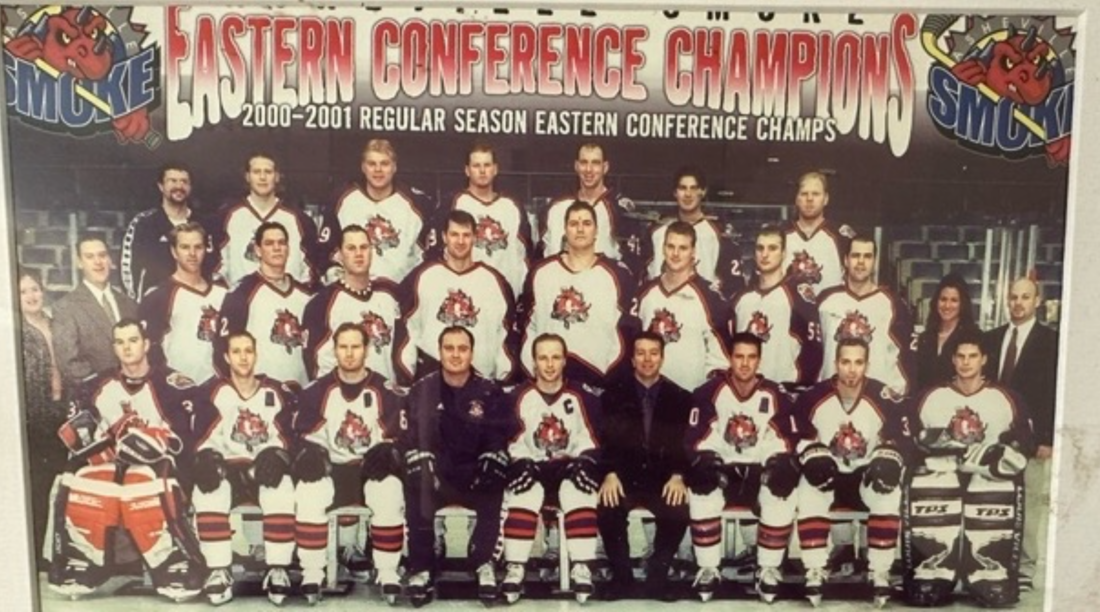

The 2000-01 season was also the Smoke’s most successful year. The team won the Southeast Division with a 45-22-7 record and dominated in the playoffs, going 6-0 and outscoring Knoxville and New Haven by a combined 28-10. Asheville advanced to the Colonial Cup finals, losing the series 4-1 to Quad City.

It was the last time the Smoke would make the postseason. The 2001-02 season saw the Smoke go 36-34-4 and just miss the playoffs.

End of an era

Numerous factors contributed to the Smoke’s demise. Just before the start of the team’s final season, the new National Basketball Development League brought the Asheville Altitude to town, and the two organizations shared the Civic Center.

By then, average game attendance for the Smoke had fallen to just over 2,500 — in one report, Wagner described a “paltry crowd of 1,748” on a Wednesday night in February 2002 — and the Smoke began losing valuable weekend home games to the Altitude. On occasion, the Smoke had to practice in Greenville and leave a day earlier for road games so they had a rink on which to train.

In the middle of the season, the Knoxville Speed filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, which Wilhelm says made it difficult to secure a bank loan and keep the Smoke going as area pro hockey was deemed too financially risky. In February 2002, as reported in the Times-News, Wilhelm was “hoping that a hastily arranged raffle … will raise the $40,000-$50,000 he says he needs to finish out this season.”

Due to different agreements with the city, the Altitude was allowed to keep all of its concession revenues while all of the Smoke’s went to the city. The Altitude also got to keep 75% of the $1 “facility fee” the city added to Altitude and Smoke ticket sales beginning in fall 2001, while the city kept all of the Smoke’s facility fee. The arrangement allowed the Altitude to survive on fewer fans and averaged 1,037 attendees its first season.

“It’s kind of one of [those] things where we’ve been playing catch-up year after year. We had a lot of expenses the first year in bringing the ice plan down here. We had some good crowds and some good revenue, but we had a lot of expenses,” Wilhelm told the Times-News. “And then the second year was kind of a break-even, but last year was kind of expensive. Making the playoffs cost us a lot of money and basically we’ve been playing catch-up all summer … and it’s finally caught up to us.”

Wilhelm considered moving the Smoke to the East Coast Hockey League, whose teams included the Greenville (S.C.) Grrrowl and the Charlotte Checkers. Though the team managed to pay its debts to the city, the Smoke folded in 2002.

“You hated to see it end the way it ended, and I wish it could have been able to sustain itself in the market,” says Wilhelm, who went into the insurance business and lives in Troy, Mich. “Asheville is a great city with great people. And we had a couple of great teams with some tremendous fans.”

Brief rebound

In 2004, Florida-based real estate investor David Waronker brought the Asheville Aces to the Civic Center as part of the eight-team Southern Professional Hockey League, which was founded in 2003. Cermak was the lone former Smoke player to play for the Aces. Though the surroundings were the same, the overall experience paled in comparison.

“Not as fun, for sure,” Cermak recalls. “I don’t think the team was really taking advantage of the opportunities they had here in town, whether it was the coach or whoever was running things. But there were definitely some good guys on the team and a good staff.”

Wilhelm says he was hoping the Aces would have success but “knew they were probably facing a little bit of an uphill battle, too.” The team went 19-37-0 and missed the playoffs, then folded prior to the 2005-06 season after failing to agree to a lease with the Civic Center.

The news coincided with the end of the Asheville Altitude’s four-year run, despite winning the NBDL title its last two seasons. The basketball team, which averaged 499 fans its final year, was sold to an independent ownership group, relocated to Tulsa, Okla., and renamed the Tulsa 66ers. In 2014, the team moved to Oklahoma City and changed its name to Oklahoma City Blue.

The rink remained and was used for public ice skating and by the Asheville Hockey League, organized through the city’s Parks & Recreation Department. But in December 2009, citing budget shortfalls and the cost of repairing the faltering ice-making equipment, Asheville City Council voted to discontinue public skating at the Civic Center.

Overtime

While minor league hockey continues in Knoxville with the Ice Bears, founded in 2002, it has yet to return to Asheville. Were the Smoke’s four years a magical, time-sensitive bubble, or might professional hockey succeed today in Western North Carolina?

“I think they would do really well,” Cermak says. “The only thing they need to do is market a little bit better and start youth hockey programs. When they get the youth involved, now the parents want to take the kids to the games, and it just turns into this whole big thing. And the city can benefit from all of it — they can charge for the ice time if there’s only one ice rink here.”

Cermak also points to the influx of hockey-loving New Yorkers in the area while Letterle notes that, besides lacrosse, hockey has been one of the fastest-growing sports in the Southeast for years. According to Letterle, who continues to compete, Asheville-area players make up 25% of the adult ice hockey league in Greenville, and while these amateurs are willing to travel for their love of the game, she’s confident that a local rink would prove popular.

“We’re close to Knoxville, Charlotte and Greenville, and Raleigh has the NHL [Carolina Hurricanes],” Letterle says. “We’re surrounded by larger teams and larger hockey organizations, so the interest is there. With the right support and the right facilities, we could totally support a hockey team.”

A lot would have to go right for hockey to return and be successful, particularly in terms of financial support. Wagner notes that Major League Baseball subsidizes minor league baseball teams, a business model that no other professional sport follows. Having witnessed the Smoke’s demise and the quick exit by the Aces, he’s somewhat pessimistic about the chances of Asheville sustaining yet another hockey team, but he doesn’t rule it out.

“I’ve learned to stop underestimating the determination of some people to bring pro sports to small cities, against all rational evidence,” Wagner says. “So, I would never say it couldn’t happen again. Although I do feel like you probably need to wait for a new generation who would be wowed by the novelty of it. And maybe it hasn’t been quite long enough for that.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.