What do wildcats, chemists and coppers have in common? All three terms were once nicknames for unlicensed distillers. Then as now, however, most folks referred to these outlaw entrepreneurs as moonshiners.

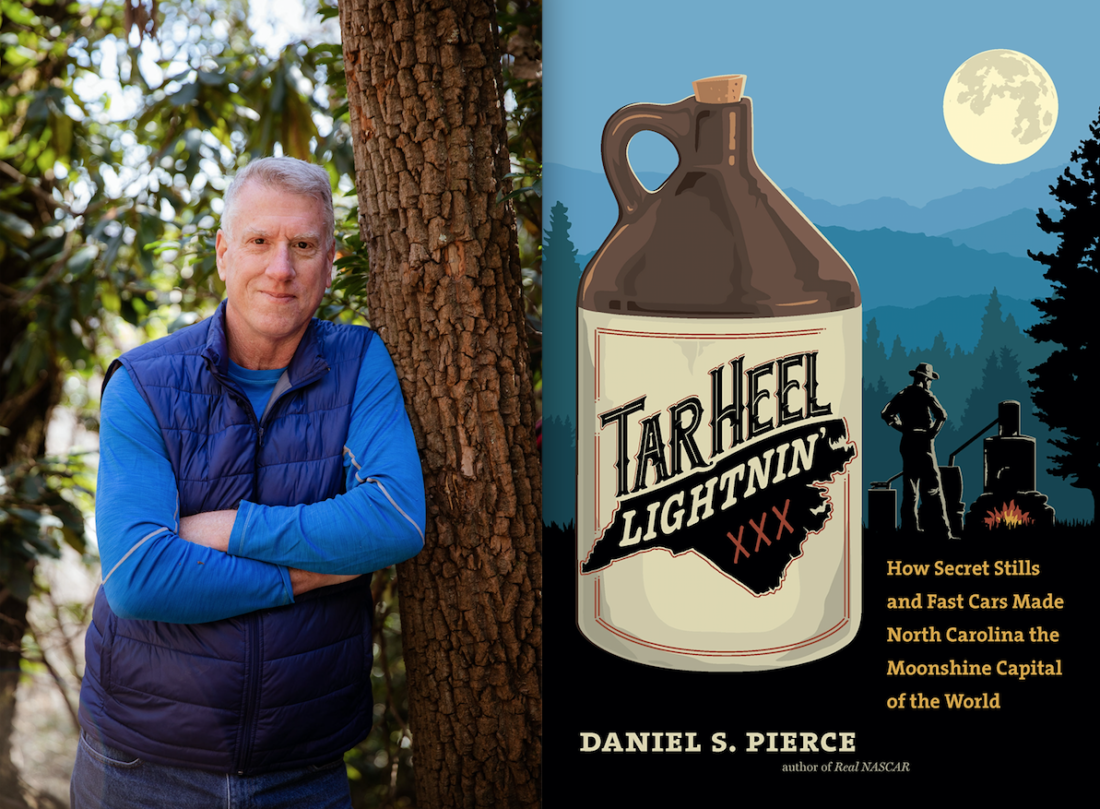

In his latest book, Tar Heel Lightnin’: How Secret Stills and Fast Cars Made North Carolina the Moonshine Capital of the World, UNC Asheville history professor Daniel Pierce offers readers a sweeping view of the industry, from its illicit start in the 19th century to its recent (and now legal) revival.

In between, Pierce serves up a nuanced look at a subject that has so often been caricatured, evoking new insight into the roles that women, African Americans and Native Americans played within the trade. The historian also skillfully spotlights major external factors — including two world wars and the Great Depression — that impacted both the practice of this criminal activity and the way it was perceived by the general public.

The industrious moonshiner

In spring 2018, Pierce spent an afternoon hiking in Montreat. Although he’s an avid outdoorsman, research is what motivated this particular trek: He was on the hunt for old moonshine still sites.

The expedition proved fruitful. Pierce and his companions, who live in the area, found old stone circles that had been used as furnaces; one of them still had a rusty steel drum inside. And meanwhile, the steep climb to reach these sites put into perspective the physical demands the old-time moonshiners had to contend with.

“It was a real revelation,” the writer says. “It was enough just to haul yourself up there, much less a still and sacks of sugar.”

One site also drove home those distillers’ ingenuity. Perched high atop a mountain, it has a water supply that flows back underground just beyond where the furnace would have been. Law enforcement, Pierce explains, often located stills simply by following streams to their source. The subterranean waterway afforded the user of this site an extra level of protection.

Pierce’s discoveries that day, he says, invigorated his research. Accordingly, his book aims to refute the cliche of the lazy moonshiner while challenging the industry’s own proclivity for mythmaking.

Granted, Tar Heel Lightnin’ contains its share of high-speed car chases and violent episodes. But cheap thrills aside, readers also come to understand the very real economic hardships that drove most folks into the business.

The many faces of the trade

Many moonshiners, notes Pierce, were ordinary farmers just trying to get by. For some, it was almost the only way to survive the harsh winter months. And once spring arrived, most of these part-time criminals simply left the business behind.

Admittedly, a majority of these seasonal distillers were young white males, but Tar Heel Lightnin’ reveals a surprising diversity among practitioners of the banned craft. Beginning in the late 19th century, says Pierce, savvy women took advantage of the country’s patriarchal legal system. Aware that female prison facilities were in short supply, many women carried out their illegal activities with a sense of impunity. And when they were caught, the historian writes, “Judges and juries often either acquitted them or suspended their sentences.”

Many of these women were widows or divorcees; some distilled, while others operated underground liquor houses. Wives and daughters also served as lookouts, making moonshining a family affair.

Meanwhile, during Prohibition, some Native American cultures decided to apply a communal approach to the whiskey trade. In eastern North Carolina, the Lumbee and Tuscarora formed networks, pooling production so they could get top dollar from the distributor.

Most African American moonshiners, on the other hand, operated sites owned by whites and received only a percentage of the still’s earnings. And with the coming of the automobile, African Americans were often hired to undertake the risky job of delivering the contraband.

Newspaper clippings from the Jim Crow era offer readers a glimpse into the nature of the industry during that period. A July 3, 1919, article in The Asheville Citizen, for example, stated:

“Men with money … are taking advantage of ignorant negroes desire to earn large sums with little work by using them as transporters. … The negroes, feeling they must protect the men higher up, take their punishment in silence while those who held out big rewards for them in the event of success let them suffer alone in failure.”

More to the story

Even within the black community, there were exceptions, however. A stand-alone section in Pierce’s book highlights Asheville businesswoman Ada Thompson. Born in South Carolina, she and her husband arrived in Asheville during the Great Depression. Thompson, says Pierce, spent much of her adult life as a domestic worker but supplemented her income by running an illegal liquor house on Weaver Street in the East End neighborhood.

There’s typically little documentation for African American involvement in the illegal liquor trade, notes Pierce. But in Thompson’s case, a 2008 multimedia project inspired by local resident Andrea Clark’s photographs proved to be a key source. Along with those historical images, “Twilight of a Neighborhood: Asheville’s East End, 1970” contains oral histories, including an interview with Talven “Sugarboy” Thompson, Ada’s son, that Pierce says was crucial for developing that section of his book. Available in the North Carolina Room at Pack Library, “Twilight” was directed by Karen Loughmiller, then with the West Asheville branch.

But while Tar Heel Lightnin’ makes a good start, stresses Pierce, “There is still a lot left to tell” concerning the roles of women, African Americans and Native Americans in moonshining. “I was able to piece together some bits and pieces,” he explains, “but I think these stories can be further fleshed out.”

Beyond rebellion

And if certain aspects of the industry’s history remain shrouded in mystery, Pierce’s book does illuminate the illicit trade’s far-reaching influence. From folk music to movies, from NASCAR to reality TV, moonshine was and still is an influential and iconic topic.

Tar Heel Lightnin’ also offers a unique perspective on major historical events. During World War I, for example, Prohibition campaigns depicted alcohol consumption as unpatriotic and pro-German. And high prices for sugar, grain and gas during World War II had an impact on the trade as well.

Lastly, like all powerful historical accounts, Pierce’s book both humanizes and complicates its subject. Stripping away cliches, it reframes moonshining as not merely a symbol of rebellion but also as the fruit of considerable ingenuity and a fundamental drive to survive.

Editor’s note: Antiquated and offensive language is preserved from the original 1919 Asheville Citizen quote, along with peculiarities of spelling and punctuation.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.