It’s been a rough spring for North Carolina’s kids. The state’s K-12 schools have been closed by the order of Gov. Roy Cooper since March 16, and gatherings outside of school have been limited to 10 people. Students expecting a return to normal have seen school reopenings repeatedly delayed and finally postponed until fall.

But as the school year reaches an end, uncertainty remains for families who depend on another childhood institution: the summer camp. Some residential camps in Western North Carolina have already announced cancellations for the season, while others are holding out hope to offer programs in late summer. And many area day camps, which are currently allowed to operate under guidance from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, plan to wait until July to resume activities.

Looking further out, the picture is even cloudier, for non-profit and privately held camps alike. According to Sandi Boyer, executive director of the North Carolina Youth Camp Association, residential camps earn more than 90% of their annual revenue over 7-10 weeks in the summer.

Camps have already suffered layoffs and revenue loss without the spring season, Boyer continues. But if they can’t operate this summer, they will face nearly 22 months without earned income. “It would be devastating for the camp industry to not open at all,” she says.

Paths to follow

North Carolina has given day camps specific instructions for cleaning and social distancing, and some are already gearing up for participants. The YMCA of Western North Carolina, for example, opened summer camps on May 18 for the children of essential workers and those looking for work. By Monday, June 1, the nonprofit’s regularly scheduled day camps will open for all children ages 4-15 — with daily health checks for all participants and rigorous sanitation. Meanwhile, the organization has closed its residential facility, Camp Watia, for the summer.

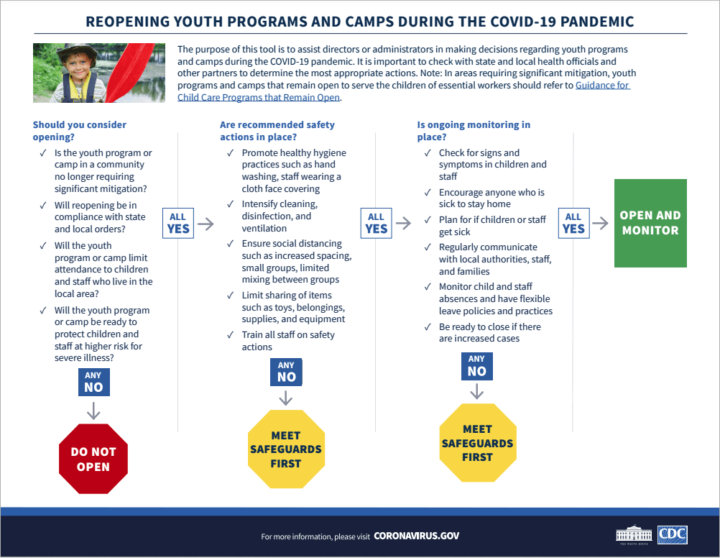

Other overnight camps remain in limbo. Boyer says many operators are waiting to get their own guidance from state officials, who in turn base their advice on guidance from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overnight camps, Boyer adds, are typically well versed in handling communicable diseases such as noroviruses, which like the new coronavirus can spread quickly in close quarters. Camps generally keep medical staff close at hand and plan for treatment spaces. A decade ago, she points out, they had to prepare for the H1N1 swine flu, but she recognizes that the current global pandemic is a different matter requiring new direction.

The CDC’s camp guidelines, however, have reportedly run into issues with the administration of President Donald Trump. On May 7, AP News published a set of draft guidelines for the reopening of businesses and services obtained from an anonymous CDC source. On the same day, according to Reuters, a source within the White House coronavirus task force confirmed that the guidance document had been shelved as “overly prescriptive.” The New York Times reported that Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, who until March 31 represented much of WNC in the House of Representatives, had taken umbrage with the draft CDC plans as being too rigid for areas with fewer cases.

Meanwhile, says Boyer, area camps needed an answer from the state by May 15 to determine if they could start back up by the usual window of mid-June. That advance notice would have given owners time to hire and train staff, acquire supplies and personal protective equipment and inform families so they could make travel plans. As of press time on May 18, the CDC had released additional guidelines for the reopening of residential camps, but Boyer was still waiting for state guidance.

The leaked draft CDC document said camps should “limit attendance to children and staff who live in the local area,” but the final CDC tool for determining a camp’s ability to reopen does not contain that language, potentially permitting more normal residential operations this summer.

The later notice may keep area camps from getting on track until later in the summer, but Boyer says they’re prepared when the time comes. “They have literally planned for every possible scenario at this point in time,” she adds.

In light of that uncertainty, Camp Tekoa, a nonprofit United Methodist-affiliated camp just south of Hendersonville, has chosen to cancel summer camp and look for new solutions. “We’d been watching this creep up on us” says Phyllis Murray, the camp’s executive director.

Tekoa is part of several large camp networks that have been counseling one another on the situation. As fellow member camps started to cancel, Murray says she initially held out, expecting increased registration and the best summer in a long time.

As of mid-April, says Tekoa assistant director John Isley, 85% of the camp’s peers nationwide were planning to run programs. By the end of the month, however, that number had dropped dramatically, and Tekoa staff decided it would be logistically impossible to hold a large camp themselves. “We originally tried to offer half of a summer,” Isley says, “and we were talking about reducing bed spaces.” But a doctor on the camp’s board of directors cautioned that those mitigation ideas wouldn’t be enough. Murray says Tekoa decided to finalize the cancellation in a timely manner, in part to give summer staff and families time to make alternative plans.

Out of doors

In this uncertain landscape, families may not be rushing to sign up for new camps. But Boyer says they aren’t rushing to cancel, either. “We see a lot of anxiousness to have their kids come to camp. Camp is such a big part of a child’s life — when they are able to do it, it just does amazing things for them,” she says. “We have a lot of parents that are waiting to see what’s going to happen.”

Growing Wild Forest School, which offers nature immersion day camps, meets on private land along the Hominy Creek Greenway. Director Kathryn Long says that, while the school’s June camps are canceled, she hopes to resume in July if the state has progressed on reopening.

“More families are coming around to this realization that their children need to be spending as much time outside in natural spaces as possible,” Long explains. “We’re anticipating that there will be more demand for our kind of programming once lockdown and quarantine is lifted for the majority of the population.”

Lena Eastes, founder of Earth Path Education, runs weeklong camps for nature connection and well-being. She also intends to restart programs mid-July, partly to give children healthy options as they’re able to leave their homes more frequently.

“Especially for teenagers and kids right now, for some of them it’s been really hard to be this isolated from their peers,” Eastes continues, “We believe that community and nature connection is so essential to well-being.” If COVID-19 cases spike, however, she plans to cancel and offer full refunds, which was typical of the local day camps that spoke with Xpress.

Forage for funding

Most of the camps Boyer works with are owned by families or are otherwise privately held. Nonprofit camps are also looking for guidance on reopening, but like Camp Tekoa, many have already chosen to cancel or cut back operations. For these facilities, fundraising may be able to cushion the losses caused by COVID-19.

Tim Brady is CEO and director of Camp Cedar Cliff, a nonprofit Christian camp located near the Billy Graham Training Center in East Asheville. During a normal year, 75% of Cedar Cliff’s revenue comes from a quarter of the year’s operation: “We survive through the fall and winter off of a successful summer,” he explains.

The camp is now under a cash flow problem, having to refund deposits as new revenue isn’t coming in. Brady says he twice cut all employees’ pay before furloughing the staff, including himself. He notes that some camps have decided to close entirely, such as Ridgecrest Conference Center in Black Mountain, which partially blamed the move on COVID-19. But he emphasizes that Cedar Cliff is motivated to make it to next year, when people will be hungry for camp.

To that end, Cedar Cliff is running a GoFundMe campaign for funds to get the camp through May. Tekoa conducted its own fundraising campaign to support operations until next season. Smaller day camps are struggling too, but many say they aren’t equipped for a large fundraising campaign and hope registrations during a less disrupted summer will cover their costs.

RiverLink’s Rivercamp usually offers four weeks of summer camp, but this year, that will likely be cut in half as June sessions are canceled. Justin Young, the nonprofit’s education and outreach manager, says his organization hopes to run camps in July, but that plan relies on the state being under the least restrictive phase of Gov. Cooper’s three-phase reopening strategy.

Young allows that RiverLink can be very conservative with the decision of whether to operate. Although the camp is an important part of its group’s mission and the proceeds help fund other education, it contributes a relatively small portion to RiverLink’s budget, which is built primarily on fundraising.

Blazing a trail

Those camps that do choose to open this summer will look different than they have before. Brady says that Cedar Cliff canceled all overnight sessions but expanded day camp programming, scheduled for the second half of summer, to include campers through 10th grade. “We feel really confident, after weeks of gathering information and looking at the regulations, that we are going to be able to provide a safe, healthy program,” he says.

The day camp will now incorporate some of the overnight camping skills that older campers enjoy, such as setting up a site and cooking over fire. Campers will also operate in pods of 10, avoiding the camp’s usual large gatherings.

Smaller groups are likely for most organizations. Growing Wild Forest School has lowered its class size from 12 campers to eight. And Long says that, as part of the camp’s usual paperwork, families will be asked to acknowledge “that the circle of contacts that a family has now includes all of the other families that attend the school.”

Participating families will also be asked to limit other social contacts to reduce COVID-19 exposure risk and make contact tracing easier if necessary. “That notion comes from discussions about modern relationships,” says Long, of incorporating what she calls radical honesty. “I think that sort of disclosure is important for us, as a society, moving out of this.”

Another way to minimize contact with people outside the household is to bring the household to camp. Alongside two weeks of its traditional day camp with expanded age groups, Tekoa is offering a full-family camp experience, including cabin rental and programming. The plan is a massive contraction from the camp’s usual activity, admits Isley: He estimates Tekoa will serve a maximum of 400 people of all ages this summer, down from around 2,400 kids last year.

Other camps are changing how they approach transportation to ensure social distancing among participants. Muddy Sneakers, which offers summer day camps based at the REEB Ranch in Brevard, usually sends older campers on day trips to paddle, fish or hike in the surrounding forests. “We have to put them in a van to visit those places,” says Lindsay Green, the nonprofit’s WNC field office director, “so that’s something we are reassessing.”

Likewise, Young says RiverLink’s camp relies on a lot of van transportation, with the entire program based on field trips. If sharing vans isn’t allowed, making camp impossible, Young says he’ll try alternatives such as field science sessions. Kids and parents might meet RiverLink staff at a stream, where they could get their hands dirty monitoring water quality and sampling bug populations.

And some camps may move beyond physical meeting altogether. Camp Heart Songs for grieving kids, run annually by the Four Seasons Foundation, still plans to hold a late summer weekend camp. The camp usually meets at Tekoa, but camp coordinator Blair Stockton says she’s working on a new location and plans to add “virtual camp,” where participants learn coping skills and connect through video chat. The sessions might include a talent show and a virtual bonfire where campers would pretend to toast s’mores.

Stockton, however, acknowledges that an online approach can’t replace the experience of being together outdoors. With families typically coming to Camp Heart Songs from all over the Southeast, she says, one question is on everyone’s lips: “Is this one more thing that we’re not going to be able to do?”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.