Establishing the county’s annual budget and the tax rate that funds it are among the most important items of business for the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners in any year. Following a 2017 revaluation that saw the total assessed value of all county property rise 28 percent, the task of determining the tax rate for the 2018 fiscal year carried even more weight than usual.

Yet in the month between the county’s first budget presentation on May 2 and a June 6 public hearing on the proposed budget, those not privy to email messages and phone calls between commissioners and then-County Manager Wanda Greene had little indication of the commissioners’ deliberations. That includes the property tax rate, which hits all county property owners squarely in the wallet.

In the budget adopted on June 20, the commissioners set a property tax rate of 53.9 cents per $100 of assessed value, which will generate 50 percent of the county’s $433 million operating budget. The rate represents a 2.6-cent increase above what’s known as revenue neutral — the tax rate that would have kept the county’s tax revenue in line with the previous year.

Xpress sought to find out what commissioners discussed outside the public view when deciding on that rate and why those conversations happened behind closed doors.

Call me maybe

On June 23, Xpress sent an open records request for emails, text messages and any other written records regarding the fiscal year 2018 budget from March 1 to June 21 “to and from all commissioners and Wanda Greene.” Further, the request stated the intent was “to understand how commissioners discuss and arrive at decisions concerning the budget that don’t happen during public meetings” and asked staff to reach out if clarification was needed. The county did not confirm receipt of the request.

On July 13, Xpress sent a follow-up email about the request. A reply advised that the county would be in touch “early next week.” Xpress checked in again July 19, and the county provided emails later that day. It soon became clear, however, that only emails sent from Greene were provided. The materials did not contain communications among commissioners.

On July 20, Xpress asked about the missing communications among commissioners. County Attorney Michael Frue responded the same day, via email: “I apologize, but it does appear that the initial query as entered was for communications surrounding Greene and the commissioners and not between the individual commissioners. As soon as I have the results I will let you know how many hits we find, however I will not be able to review them in short order.”

As of press time, Xpress is waiting on the missing communications.

Party line

The part of the open records request the county did fulfill showed emails from Greene — a total of about 40 emails and threads. The emails, by and large, contained little discussion about the budget. Most deal with commissioners’ requests for information or setting up meetings.

On April 26, Greene sent an email to all commissioners outlining her proposed 55.9-cent property tax rate, 2 cents higher than the rate the officials eventually adopted.

In the email, Greene explained that the purchase of 137 acres on Ferry Road (undertaken as part of a failed bid to attract Deschutes Brewery) and expenses related to the new Health and Human Services building on Coxe Avenue made it necessary for the county to generate additional revenue.

Greene wrapped up the email to commissioners with a request that budget communications take place by phone: “As you review the budget, please call me with any questions.”

Phone tag

On May 2, Buncombe County commissioners held their first public meeting about the proposed budget and property tax rate. Greene floated a $419 million spending plan with the associated property tax rate of 55.9 cents she had quoted commissioners the week before. Ultimately, commissioners approved a rate of 53.9 cents on June 20.

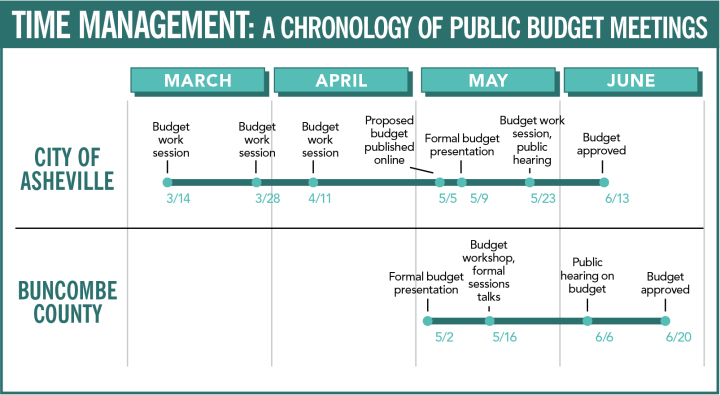

By comparison, the city of Asheville kicked off its budget season on March 14 and held four work sessions, along with a formal budget presentation, public hearing and formal adoption, for a total of seven public discussions. The county got started on May 2, held one workshop and discussed the spending plan at three formal meetings — a total of four public occasions.

The city’s adopted budget of $175 million is less than half the size of the county’s $433 million budget.

Commission Chair Brownie Newman, helming his first budget process, says most discussions about the property tax rate happened between the June 6 public hearing and the budget approval on June 20.

“This is a topic that every single commissioner understands is one of the most important decisions,” he says. “What’s the right number? There was a lot of conversation between commissioners and staff after the public hearing to see how much lower we can reduce it while not reducing it so much that we can’t meet key priorities we want in the budget.”

Newman says those conversations mostly happened via in-person meetings and phone calls, leaving very little in the way of a paper trail. “As we were getting close, I called commissioners to ask where they were at,” says Newman.

Conference call

Newman explains that commissioners take advantage of three-on-one meetings that feature three commissioners and the county manager; sometimes, other county staff attend. Limiting the meetings to three elected officials avoids convening a quorum, which would trigger legal requirements to advertise the meeting and keep minutes of the commissioners’ interactions.

Commissioner Mike Fryar says those types of informal discussions are necessary. “You have to do certain things in any job where you discuss stuff before it ever happens,” he says, noting those in-person and by-phone discussions were influential in lowering the proposed property tax rate from 55.9 to 53.9 cents.

Fryar touts the success of the commissioner-staff meetings and notes Republicans and Democrats were always paired together. “I don’t want to get seven of us together in the middle of a storm to try to figure it out. I’d rather it be three-on-one, get close and then figure it out. I can’t call [the media] in my office every time I do something. I got hired to try to do a job for the people,” he says.

Chris Cooper, head of Western Carolina University’s political science department, says it’s normal for nonpublic government negotiations to take place, but it’s a tightrope act. “We want as much light shed on government as possible, but the reality is that elected officials are human beings, and it’s unrealistic to think that all of the discourse on complicated issues will take place in a meeting,” he says.

Frayda Bluestein, a professor of public law and government at UNC Chapel Hill, says she’s not aware of specific guidance about what public officials must discuss in the open. “It’s quite common for individual members to talk with other members. A concern arises if it’s a majority discussing it simultaneously, as this triggers the open meetings law. Negotiating — ‘horse trading’ — is pretty common in the political decision-making process,” she says.

Private number

What did commissioners discuss during private meetings and phone calls?

“It ended up kind of being a debate between 54.5 and 53.9. Those were the two numbers that there was some support around,” says Newman of the off-the-record talks. “I was in 54.5 camp, but eventually I was persuaded that 53.9 could work.”

Commissioner Jasmine Beach-Ferrara says the meetings allowed for more in-depth discussion of policy issues and fostered a spirit of cooperation. “Between regular meetings with the county manager, staff and other commissioners, it was much more discussion than debate-oriented,” she says.

Beach-Ferrara says commissioners discussed forecasts prepared by county staff showing the effects of different property tax rates. “The driving force on that was people wanting the tax rate as low as we could get it.” To test those theories, she says, the idea was, “Let’s run the numbers with different tax rates and see what the implications are.”

Fryar says the talks allowed him to budge from his original stance on the property tax rate. “I was at 53 [cents]. I took all the numbers and figured them. Whatever we do is going to help somebody, hurt somebody, and somebody is going to break even,” he says, noting he started even lower, at 51 cents, but couldn’t see it working.

Dialing for dollars

The emails Xpress received offer some insight into what commissioners and the county manager discussed. Community grant funding proved a contentious topic. On June 12, Newman sent an email to Greene with a spreadsheet outlining suggested figures for such funding. That spreadsheet was not provided to Xpress.

The community grant funding process, Fryar tells Xpress, is “a waste of time.” Overall, he’s opposed to the grants: “I didn’t like the money that we gave away to nonprofits. It’s a budget where it’s everybody wanting something for nothing.”

While she didn’t have to fight for her priorities, such as funding for preschools and combating opioid addiction, Beach-Ferrara notes the community grant funding was a bit divisive.

Newman acknowledges that commissioners often have grievances with the budget when projects they support don’t make it in. “It’s about what they can ultimately live with. It’s asking people, ‘What do you really need in this budget to support it?’” he says.

It’s your call

“It felt really crunched,” Newman says of the county’s timeline for creating the budget. He’s open to starting the process and holding multiple public work sessions. “We should create more space for this to play out, both publicly and with informal commissioner discussions.”

Fryar says his lone vote against the budget had to do with his opposition to rerouting the dedicated A-B Tech 0.25-cent sales tax from capital projects to operations and maintenance needs. Nonetheless, reflecting on the process, he says, “Overall, we did good together.”

Fryar is enthusiastic about new County Manager Mandy Stone, who took office July 1 after Greene’s retirement. “We are going to see everything ahead of time, before it hits me in the face,” says Fryar, explaining that in previous budgets he often received information last minute.

New debt transparency projects county staff is rolling out, says Fryar, will help inform commissioners and the community. However, he’s not sure all discussions need to happen in public. “We need to come close, then we hash it out in a forum or a meeting,” he says.

Beach-Ferrara says she’s pleased with her first budget process. Still, she thinks there’s room for improvement: “I would be excited to look at ways the budget process could involve more opportunity for public comment and participation, and I think there are ways to do that in the next year.”

Don’t hang up

While Newman believes there’s value in commissioners holding more public discussion, he doesn’t want to put the kibosh on the free flow of conversation away from public scrutiny as long as it occurs within the letter of the law. “I think most people in the community want us to be talking to each other between the meetings — not just Democrats talking to Democrats, we should all be talking together,” he says. “I think informal conversations are helpful to the process.”

WCU’s Cooper says the road to transparency is not always clear. “We all want openness, but at the same time, it’s hard to see the sausage being made, as policymaking is a long and tedious process,” he says. “The reality of political life is that once things hit the floor, the major decisions have usually been made. It’s not unusual for decisions to be made this way, but I think no one would argue that it’s optimal.”

Xpress reached out to the other four commissioners but did not receive responses by press time. The three commissioners Xpress spoke with all say they want more time to develop future budgets. Just what strategies county staff and elected leaders will use to promote more transparency, encourage public input and provide a forum for discussing community grant funding and the tax rate remain to be determined.

As the requested emails between commissioners become available, Xpress will report on any new information those communications reveal about the process.

Unreal. Why are these crooks in government?

If only there were a way for people with strong negative opinions about local government to lay out an alternative approach, be publicly accountable for their beliefs, and seek to replace the incumbents. You could call that process “an election.”

Focusing on this piece: the quorum / open meeting rules seem counterproductive. The intent is obvious and — to avoid government in secret — but when it’s finagled around with round-robin 3+1 meetings, it’s inefficient and inevitably looks more nefarious than if the county commissioners (or city council) were simply able to hold off-the-record meetings with staff in whatever numbers best make sense. There needs to be some kind of venue that allows for a degree of candor and generosity in working through complex issues like the ripple-through effect of different property tax rates on the budget., without the immediate partisan feedback loop that tends to come from hashing things out in public. I’m at some political distance from Mike Fryar, but I respect the approach he’s taken to the nuts-and-bolts business of county government.

…behind closed doors, huh? Just like trump. Pathetic.

You mean Obama and the planes full of cash headed to Iran.