by Frank Thompson

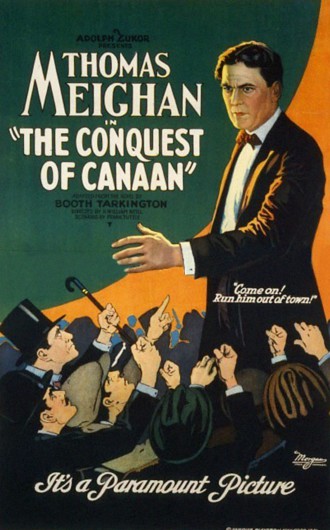

For local film aficionados, The Conquest of Canaan, which will be screened at Grail Moviehouse on Sunday, Jan. 22, offers more than a movie. Shot on the streets of Asheville in March 1921, Conquest is a trip in a time machine, a tour of a lost city, a stroll past homes, neighborhoods, businesses and churches that today exist only on film.

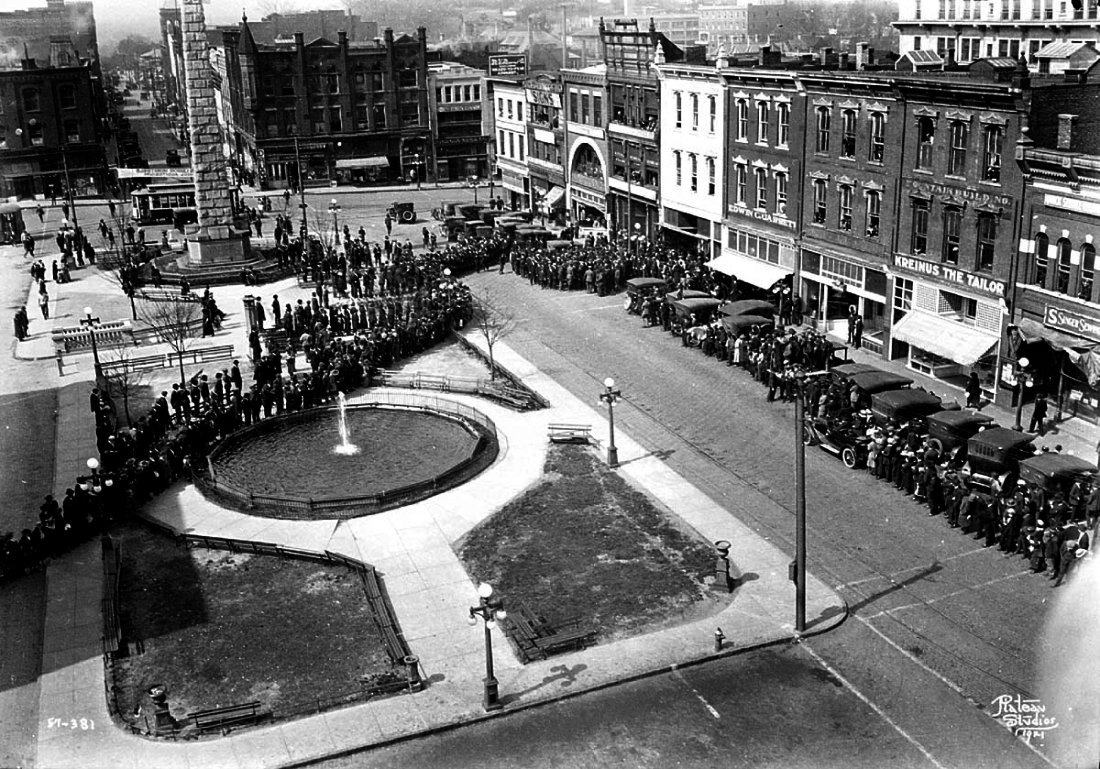

Every movie, to some extent, contains within it a kind of accidental documentary of the time and place in which it was made. When a film is shot on location, as The Conquest of Canaan was, the background can emerge to become the main subject. Based on Booth Tarkington’s 1905 novel, Conquest’s story and characters are compelling. But watching the film here nearly a century later, the main attractions are those precious images of Pack Square, the Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel on Biltmore Avenue, the trolley cars, the long-gone First Baptist Church at College and Spruce, the Southern Railway station, City Hall, the vanished fire station, the old Patton-Parker House at the corner of Chestnut and Charlotte, the original Pack Memorial Library, the Princess Theatre and so much more.

Because of all that, Asheville residents could easily forget that the story is set in Indiana; Tarkington was, after all, the quintessential Hoosier. Joe Louden (Thomas Meighan), a young ne’er-do-well, repeatedly goes up against Canaan’s establishment, in the person of Boss Pike (Louis Hendricks). When his lifelong friend Ariel (Doris Kenyon) inherits a fortune and heads to Paris, Joe also leaves Canaan to study law. But he returns to defend the underdog, fight corruption and redeem himself in the eyes of his hometown.

Famous Players-Lasky had a studio on each coast. The task of adapting Conquest for the screen was handed to the New York branch. But filming in Indiana — or New York, for that matter — during the winter was problematic, so the studio looked south for a suitable location. In February 1921, the Asheville Board of Trade received a telegram from Paramount asking if there might be a place in Western North Carolina that offered a “town square, courthouse, buildings similar to a small western town of about 3,000.” The quick reply, according to the Asheville Citizen, assured Paramount, “There isn’t anything we can’t supply in the way of scenery.”

Heart and soul

Location manager Arthur Cozine arrived on March 3, 1921, and immediately recognized that Asheville was the place. Before day’s end, he’d telegraphed Paramount instructing them to send along the cast and crew right away. Roy William Neill was the director, and newcomer Frank Tuttle wrote the script. Meighan and Kenyon’s supporting cast included Diana Allen, Alice Fleming and Meighan’s brother-in-law Cyril Ring.

On March 6, 1921, the Asheville Citizen’s headline proclaimed, “Lasky Company Arrives Today for Filming of Great Picture.” The company was met by a passel of city officials. A banquet that night was only the first of many such festivities. Those social and civic obligations made working on the film an around-the-clock endeavor. They worked all day on the streets of Asheville and, at night, attended functions hosted by Kiwanis, the Rotary Club and the American Legion. Kenyon and other members of the troupe visited the Asheville Jail and handed out cigarettes to prisoners.

The company went out of its way to endear itself to both press and public. When an Asheville Citizen reporter was interviewing the Swedish-born Diana Allen, Meighan elbowed him aside, saying, “Let me interview her.” Turning to Allen, he said: “Do you ever fall in love with the leading man? When he caresses you, do you put your heart and soul into it?” Allen laughed loudly, and readers were assured that the movie stars were charming, affable and, most important, nice.

It didn’t take much to transform Asheville into Canaan. One trolley car was fitted up with a sign reading “Canaan Rapid Transit Co.” The Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel’s picture window was repainted to say “National House,” and a sign reading “Joseph Louden: Attorney at Law” was placed on a stairway entrance at 8 1/2 N. Pack Square, between H. Petrie, Tailor, and C.D. Kenny importers. For one day, the new Emporium Department Store was rechristened “Pike’s Emporium.” Unfortunately, that particular day had been slated for an Easter sale that had been advertised for weeks. The sale was bumped back a week, and to make up for the loss, Meighan, Kenyon and their co-stars showed up to host the event. The crowds were so big, the Emporium’s owner had to stop letting people in.

The shooting began March 9, with Thomas Meighan boarding a trolley car at the corner of Broadway and Patton Avenue. That scene actually appears more than halfway through the film.

Storming the courthouse

Ironically, since Asheville was chosen because of its climate, bad weather plagued the production. Several days of shooting had to be postponed or, in some cases, reshot due to rain. And when it wasn’t raining, the skies were dark and cloudy. A couple of locals, interviewed years later, remembered all the “mirrors” at every setup. These reflectors were used to throw as much extra light as possible.

The film’s outdoor locations are remarkable enough, but some scenes show interiors that can be seen almost nowhere else, and certainly not filled with such lively motion. Neill filmed in the lobby and cafe inside the Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel as well as the basement of the building at 22 S. Pack Square, which had once been the home of the monument shop owned by Thomas Wolfe’s father, W.O. Wolfe. In the movie, it’s a pool hall.

On March 21 and again on the 26th, the company was allowed to shoot the film’s trial scene inside an actual courtroom. Even more remarkable, the notorious Slagle trial, in which three brothers were accused of murder, was just ending, and Neill asked the jurors if they’d be kind enough to stick around and play the jury in Conquest. They agreed. Asheville attorney R.S. McCall played the judge, and Register of Deeds George A. Digges played the court clerk.

Throughout the filming, the streets were lined with onlookers. Two mob scenes in Pack Square, as well as a scene at the railway station, required large crowds. Ads in the local papers notified readers when and where the company would be filming. Each time, people showed up, sometimes numbering in the hundreds. If not enough people responded, passers-by were offered $5 to appear in the scene. The publicity department claimed that 6,000 locals appeared in the film.

“One sequence in the script called for the crowd to storm the courthouse,” Frank Tuttle recalled in his memoir, They Started Talking. “Neill shot all the medium and close setups first, his camera angled toward the building. During these preliminaries … assistants and the local police roped off the spectators who had come for miles to watch us. Meanwhile, Roy had a second camera ready to set up inside the doorway, shooting toward the watching crowd. … As soon as the second cameraman was ready and signaled the assistants, they dropped the ropes and urged the watchers forward. The milling hundreds stormed the courthouse as though it were the Bastille. It was a dilly.”

Friendly and hearty cooperation

At the end of March, most of the company left for the New York studios, where the bulk of the interiors were filmed, as well as a shipyard scene and the exterior of the “Beaver Beach” roadhouse. Cameraman Harry Perry and a small crew remained behind, hoping for one more sunny day.

On April 3, the Citizen ran an ad stating, “Mr. Thomas Meighan and Mr. R. William Neil [sic] and the members of the company, before leaving for their studio in New York, wish publically to thank the people of Asheville for their friendly and hearty co-operation in the filming of — ‘The Conquest of Canaan.’”

The movie opened in Asheville’s Majestic Theatre on Aug. 15, 1921. An item in the Citizen testified that “Asheville people were delighted with the story, with the acting, with scenes of their home town — and with themselves.”

There’s an unfounded belief — perpetuated by many an article on the subject — that the film received scathing reviews everywhere but Asheville and was a box-office bomb. In fact, the reviews were overwhelmingly positive nationwide. The Washington Times called it “brilliant.” And even in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where locals were pretty protective of Booth Tarkington, The News-Sentinel called it “a superb cinematic treat … as attractive as it is artistic and satisfying.” The few negative reviews were mostly of the “not as good as the book” variety.

The Conquest of Canaan was not a blockbuster, but it did turn a profit. And “profit” does not spell “bomb” in any language.

Up in smoke

There’s one important difference between The Conquest of Canaan and the many earlier films produced in Asheville. While those other movies were being made, the people of Asheville were mere spectators; for Canaan, they were participants. Each of them could cling to the dream that his or her face would somehow end up on the screen.

And many of them were right. Few, however, could have guessed that nearly 96 years later, their faces would once again be seen on a local screen.

It’s something of a miracle that The Conquest of Canaan survived at all. In the days before television, video and the internet, most films were considered obsolete after their initial release, as irrelevant as last week’s comic strip. Only select stars — Charlie Chaplin, for example — merited a rerelease of their older films.

We don’t know precisely what happened to the prints and negatives of Conquest. According to historian/archivist David Pierce’s comprehensive 2013 survey, The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912-1929, only 361 of Paramount’s 1,222 silent features survive. The reasons range from vault fires to the volatility of nitrate film to studio policies of junking films taking up valuable vault space. Sometimes when a film required a bonfire scene, someone would just go into the vaults and bring out some nitrate film, which burned brightly and beautifully.

In the 1960s, however, many “lost” American features started turning up in foreign archives. Moscow’s Gosfilmofond has been a rich source of such discoveries, as has the Czech National Film Archive. When these films were first released, American studios generally felt it wasn’t worth the shipping cost to reclaim prints from such faraway places. Russia and Czechoslovakia understood the importance of film preservation much earlier than almost any U.S. institution.

In the late 1980s, WLOS producer Bill Banner began searching for The Conquest of Canaan, recognizing it as a precious piece of local history. Doug Swaim of Asheville’s Historic Resources Commission joined the hunt. “We called all the major film archives and, at first, no one had even heard of it,” Swaim told Citizen staff writer Tony Kiss in 1989. Swaim said that someone at New York’s Museum of Modern Art had noticed that Gosfilmofond held a print. “We wrote to [Moscow], and they were extremely accommodating,” Swaim recalled. “They were willing to make us a copy for just over $1,000.” The Historic Resources Commission raised $1,260 to make the purchase in September 1988.

This print, which still had Russian intertitles, had one public showing in 1989 at the Beaucatcher Cinemas. As the film unspooled, a Russian speaker translated the titles on the fly.

After that, however, nothing. The print eventually ended up in cold storage in UNC Asheville’s D.H. Ramsey Library, but it was never shown again. On Dec. 13, 2016, Asheville’s mayor and City Council, acknowledging that both the university and the city “lack appropriate long-term facilities,” agreed to donate the print to the Library of Congress.

By the time Asheville’s print arrived there on Dec. 21, the Library of Congress was already moving forward to preserve The Conquest of Canaan. In 2010, Gosfilmofond had given the library digital scans of several features that no American archive held, Conquest among them. The library is now negotiating to access the original nitrate 35mm print from Moscow in order to do a full restoration, which will result in a new 35mm negative.

Labor of love

Earlier this year, I obtained a digital copy and started working to make it suitable for screening. First, I enlisted the aid of Irina Kipervaser, who translated the intertitles from Russian. I then “retranslated” the translations (going from English to Russian and back to English is a bit like a game of telephone). For guidance, I referred to Tarkington’s novel as well as the only surviving script, a first draft that has only a marginal connection to the film as it was eventually released.

Earlier this year, I obtained a digital copy and started working to make it suitable for screening. First, I enlisted the aid of Irina Kipervaser, who translated the intertitles from Russian. I then “retranslated” the translations (going from English to Russian and back to English is a bit like a game of telephone). For guidance, I referred to Tarkington’s novel as well as the only surviving script, a first draft that has only a marginal connection to the film as it was eventually released.

The translated intertitles were sent to graphic designer David B. Pearson in Mississippi. He redid them in the font used by Paramount in 1921 and created an era-perfect Paramount logo and credit titles. Finally, Steve White of Grail Moviehouse edited the titles into my digital copy.

The Jan. 22 screening will be the first time in nearly a century that a theater audience will see this film in something like its original form. The event will feature live music by Asheville stride pianist Andrew Fletcher, an accomplished silent film accompanist. I will introduce the film and answer questions afterward.

It may be years before the full 35mm restoration is completed. But in the meantime, after a journey of many decades and thousands of miles, The Conquest of Canaan has come home.

Asheville resident Frank Thompson is a writer and film historian, the author of more than 40 books and nearly 2,000 articles. His next book is Asheville Movies Volume I: The Silent Era. He can be reached at thompsonesque@gmail.com or thecommentarytrack.com.

Got my ticket! I have long wanted to see this movie. I can remember a lot of buildings that used to be downtown prior to 1921, but many of them are gone. I believe that the group of buildings on the west side of the Square – Finkelsteins, G’s and the Pack Square Cigar Store – may have predated 1921. And of course, the Vance Monument was built in the 1890’s. There are a sprinkling of pre-1921 buildings around downtown – and quite a few pre-1921 homes in various neighborhoods. Will be especially neat to see motion picture footage of the old Depot and the streetcars.

Great article! Wish I were there to see the film.

Great article, and it fills in a lot of the historical details I did not know. I was the anonymous “Russian speaker” you mentioned, and I interpreted the movie’s Russian-language storyboards at the Beaucatcher showing in 1989. It wasn’t entirely “on the fly” – I went back and read the book “The Conquest of Canaan” to prepare for what we call a “sight translation.” The showing went pretty well! I was a professional Russian translator and interpreter for 27 years. Though the story is set in Indiana, it’s a true time capsule of Asheville circa 1920. I enjoyed the parts showing characters riding trolleys around Asheville, because my great-grandfather was a trolley conductor in Asheville in 1902-04. I’d love to see it again!