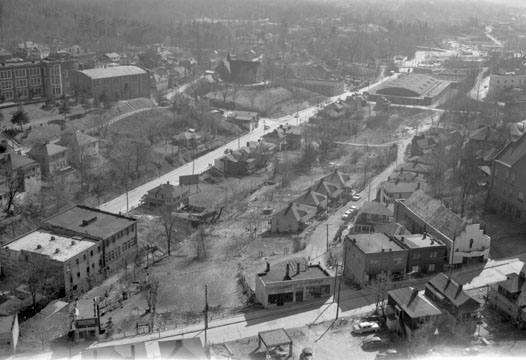

Conversations about the East Riverside Urban Renewal Project began in the mid-1960s. The project’s goal was to provide more public housing in Asheville. It wouldn’t be until 1977 that the plan would go into effect. The government-funded project sought to build 1,300 new homes on 425 acres. However, in order to accomplish this, many residents were displaced and existing properties destroyed. At the time, East Riverside was home to nearly half of Asheville’s African-American population.

For some in Asheville, the proposed East Riverside Project offered great promise. A Dec. 4, 1967 Asheville Citizen reader-comment column, “Backtalk,” included several encouraging comments on the topic.

Resident Pamela Beens implored the community to “show how much they really care about their city and its future,” by voting for the proposed East Riverside Project. Beens concluded her letter by insisting that readers “get rid of public apathy.”

In a similar vein, Les Stradley urged residents to show more pride in their community. Stradley wrote:

“I am a student at Furman University and am concerned over the lack of interest in progress in Asheville. Several very worthy projects such as a supplemental tax for schools, and urban renewal have been voted down. Many more plans will be voted against unless there is a change in attitude of many of our citizens. …

Asheville has a lot of good potential which will be washed down the drain unless we make up and take a little more pride in our community.”

A third contributor, resident David M. Williams, argued that urban renewal would improve property values and thus increase tax revenue. Williams wrote, “The only people who should be opposed, it seems to me, are some of the landlords in the project area who would lose a very lucrative real estate investment. These people are paying low taxes and spending little or nothing on maintenance of their substandard buildings.”

In recent years, several local historians and institutions have documented the impacts of Asheville’s urban renewal projects. During the early 1990s, Dorothy Jones headed the Voices of Asheville Project, which can be accessed at D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections at UNC Asheville. In it, she interviews former residents of East Riverside.

On April 15, 1994, Jones spoke with Oralene Anderson Graves Simmons about urban renewal’s promises. During their talk, Simmons, the first African-American to attend Mars Hill College and the founder of Asheville’s Martin Luther King Jr. Prayer Breakfast, said:

“When I first came to Asheville, [East Riverside] was a very thriving community, a black community with what they called homes and not so much houses. They were homes that were owned by black people. It was considered a blight area and the city received some money for redevelopment. The people were offered a price for their home and also relocation assistance. They took this. Some of them bought homes in other areas of the city, quite a number of them went into public housing. They moved from this area with the belief that with the redevelopment of this community [the Asheville Redevelopment Commission and Asheville Housing Authority] were going to put homes back into this area … which really … has not materialized to that extent at this time. It was replaced with some public housing. … The promise that they were going to put homes back got changed to rows and rows of public housing and at that time there was a cry from the citizens that we don’t want anymore public housing, we want homes.”

In a separate interview, on Dec. 1, 1994, Jones spoke with Robert “Bob” Smith, who was displaced during urban renewal. According to Smith:

“Some good things happened [with urban renewal]. Folks had heat in their houses. The water ran. They didn’t have to haul coal anymore … But there are some negative things as well … You certainly lost ownership … People were uprooted and disconnected from where they were and that led to a disharmony. I remember a whole lot of old folks dying shortly after relocation began and they were moved into high-rises and moved into apartments for elderly. A whole lot of people just seemed to be dying off. It’s certainly bittersweet when you look back at those days. I think what we lost was community, and I’m not sure how, if you can ever get that again.”

Next week, Tuesday History will look out the Asheville High riot of 1969 when the high school was integrated.

I appreciated and understood the comment from Mr. Bob Smith in 1994 – it is almost exactly what I have said for years regarding the changes around Valley Street and Southside. The area was generally rundown and aging, but there was a sense of community, and most of the longtime residents provided a stability that went away with them. It is interesting consider what might have happened had the money been used to improve what was there instead of destroying it and uprooting the residents.

I know that hindsight is 20/20 and that it is easy to look back and see what should have been done, but I do think that the focus of the Urban Renewal advocates was off – they seemed to be more centered on the appearance of the place, “civic pride” and such, rather than the actual well-being of the residents and their future – at a time when Asheville, despite tourism, was very much a working city.

I was not in Asheville during the transfer of black students to Lee Edwards in 1969, but I have heard that many of them resented the closure of Stephens-Lee and having to go somewhere else. The integration of blacks into schools in Haywood County did not cause any problems I remember – there were very few black folks there – I can remember only 5 black students out of my own graduating class of almost 300 and they just blended in.