In October 1918, in the midst of a worldwide influenza pandemic, Asheville residents opted to wear medical masks as opposed to Halloween costumes.

In October 1918, in the midst of a worldwide influenza pandemic, Asheville residents opted to wear medical masks as opposed to Halloween costumes.

In 1941, two years before the Asheville Colored Hospital opened, Asheville’s African-American population numbered 14,500. At the time, the segregated city only had 21 hospital beds available for the entire African-American community.

In May 1927, work officially began on Beaucatcher Tunnel. Controversy and catastrophe would haunt the two-year project.

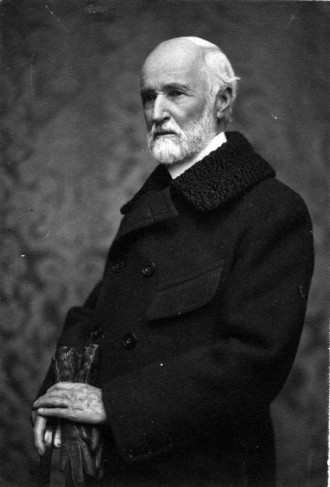

On Aug. 31, 1906, Asheville mourned the loss of George Willis Pack.

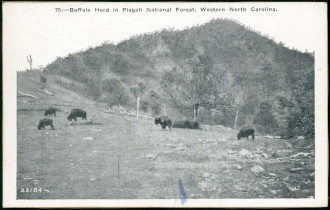

In 1916, plans were underway to bring herds of elk and buffalo to Pisgah Forest. Difficulties and delays would plague the project.

Anna Aston, Fannie L. Patton and Anna Chunn were among the earliest advocates for a library in Asheville. The institution finally opened in May of 1879.

On March 11, 1890, the the Buncombe County Children’s Home opened.

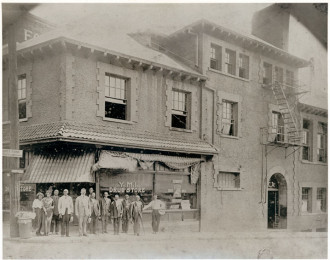

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, Asheville’s African-American community took to the streets on Jan. 1 of each year to celebrate Emancipation Day.

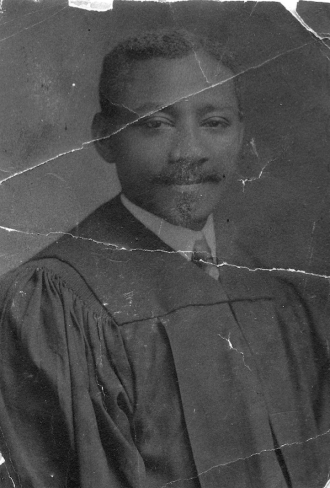

In 1906, Dr. William Green Torrence arrived in Asheville. Four years later, he would set up the city’s first African-American hospital inside his home on Eagle Street.

The Langren Hotel opened on July 4, 1912. It had 210 rooms and was capable of accommodating 500 guests. The city celebrated the new hostelry. Meanwhile, the Asheville Gazette News declared it “the most important achievement in the way of provision for the tourist business, in western North Carolina in a decade.”

In the mid-1920s, a daredevil arrived to Asheville ready to scale the city’s tallest buildings.

Tempie Avery was a midwife, nurse and former slave of Asheville attorney and state senator Nicholas Woodfin.

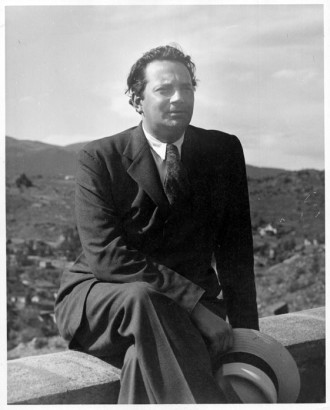

October was a significant month in writer Thomas Wolfe’s life. The Asheville native was born Oct. 3, 1900. Decades later, his first novel, Look Homeward, Angel came out on Oct. 18, 1929. Local responses were not favorable to Wolfe’s book.

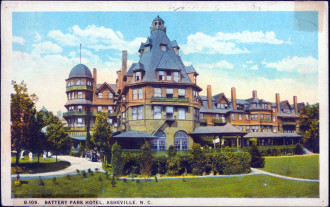

Anticipation for Col. Franklin Coxe’s Battery Park Hotel was evident in early newspaper reports.

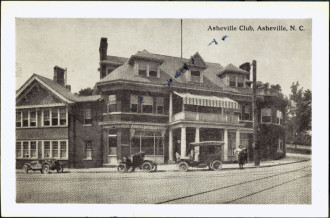

On Wednesday, Oct. 23, 1901, The Asheville Citizen offered readers a detailed description of the Asheville Club’s new headquarters built on the corner of Haywood and Government [now College] streets.

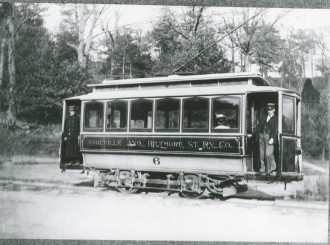

After 45 years of service, the final seven street cars departed from Pritchard Park on Thursday, Sept. 6, 1934, heading toward West Asheville for one last ride.

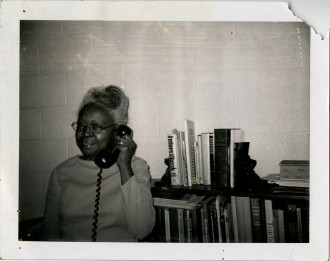

“[F]or roughly half a century, two YWCAs operated in Asheville, operating the program that is the YWCA. And during all these years parallel programs were operating in our city,” says Thelma Caldwell, in her 1981 speech at the YWCA’s annual meeting.

On October 24, 1970, Virginia Bailey, president of the Asheville YWCA, shared with the Asheville Citizen the most common complaint the organization received following the announcement: “‘We want our white Y; it is as important to us as the South French Broad branch is to the blacks.’”

In 1969, Roger Ball was a senior at Asheville High School. He was also the school’s photographer. Before the walkout occured, Ball was asked by Principal Clark Pennell to capture the day’s events on his camera.

Conversations about the East Riverside Urban Renewal Project began in the mid-1960s. The project’s goal was to provide more public housing in Asheville. It wouldn’t be until 1977 that the plan would go into effect. The government-funded project sought to build 1,300 new homes on 425 acres. However, in order to accomplish this, many residents […]

In 1965, Thelma Caldwell became the Executive Director of the Central YWCA in Asheville: the first African-American in the South to hold the position.