Walk out in the street and ask anybody — ask the beggars or the tourists, ask the hippies or the bible-thumpers, ask the artists or the accountants — and they will tell you: The world is going to hell.

As a photographer, this means good things for me.

I’ve been running an art blog called A Dark Topography for several years now. It’s a first-person account of what the Art World calls an “emerging” artist. The Art World has names for everything, especially folks like me. The problem is that I’ve been “emerging” for a good long while, and I’m beginning to suspect that this cocoon is made of Kevlar.

But photography is a lot of fun, and I like talking about film and cameras and capital-A Art with random people on the Internet. But lately — and I’m being serious, here — I’ve had a bad feeling. We can argue about its cause, or debate its solution. You can subscribe to whichever doomsayer you’d like. But when you walk out in the streets among your fellow men, I suspect you feel it too.

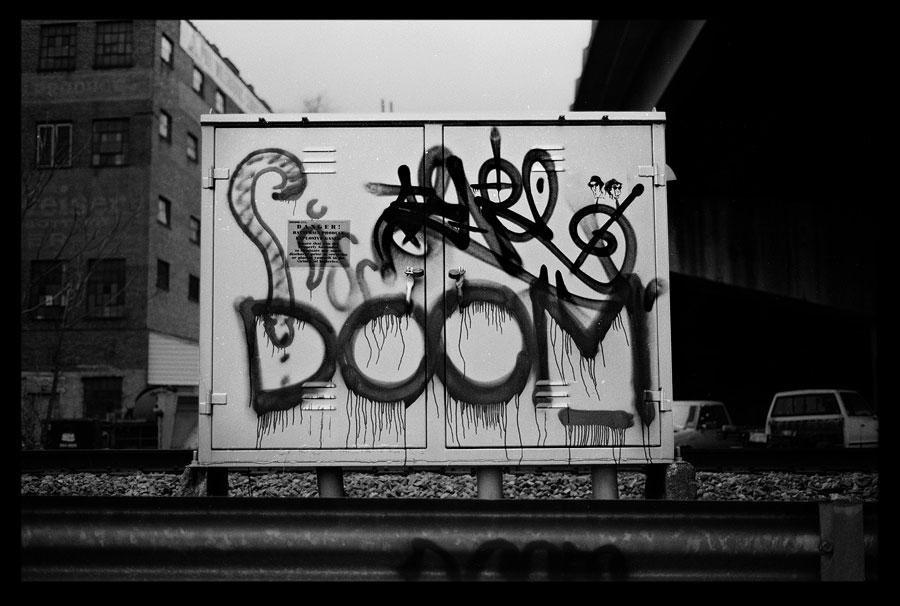

I think the world is going to hell.

Ansel Adams is arguably the most famous art photographer in history. Long before anyone ever heard of a photo blog, he was exposing glass plates in view cameras. In 2011, deep into this new digital age, I teach young photo students the concepts Adams distilled and perfected in the 1930s and ‘40s. His landscape work in the American West is the standard by which other such work is judged.

But there was another photographer, one of Adams’ contemporaries, named Henri Cartier-Bresson. In that same troubled time, he was shooting photos of the streets in Europe. There’s an apocryphal quote attributed to Cartier-Bresson: “The world is going to pieces and Ansel Adams is photographing trees and rocks.”

Human beings simultaneously seek and hide from the truth. Everybody lies, but some people lie more than others. Some people claim not to lie at all. We call those people journalists.

Every photo is a fish tale. Look at the math: An average wide-angle lens shows 70 degrees of a 360-degree scene. An average exposure covers less than a hundredth of a second. You get to cast your line into the world’s river for only the tiniest moment — aren’t you going to try to land the big one? You’ll gut it and clean it and mount it on the wall, and if an observer didn’t know any better, he’d think there was nothing but giant fish in the river.

We are drowning in journalism. The modern flow of information grants to media what Christ granted to his disciples: so many fish that the boat begins to sink.

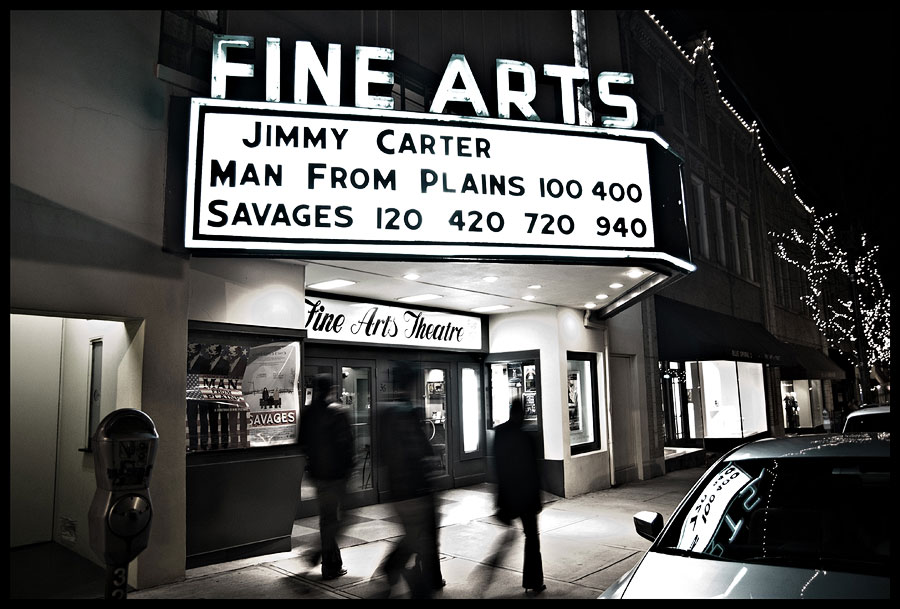

So I’ve had this idea in my head for awhile now, sort of an art project: a news stream in which the headlines come from indistinct moments in Asheville’s streets. Instead of “Coalition Forces Invade Iraq” or “Twin Towers Collapse,” the headlines would read “Fog Invades Ally” or “Bum Collapses in the Street.”

After all, most of life takes place between the headlines. For every birth, death and wedding, there are 10,000 drives to work, a million cross glances, a 100 billion wishful thoughts. As naked Molly says, “In Asheville, there’s no such thing as just a cup of coffee.”

Newspapers sometimes take the name “Argus.” In Greek mythology, Argus was an ancient giant with a hundred eyes, employed by the gods as a watchman.

I have no illusions that my art project will keep the world from going to hell. But at the same time, I have little motivation to keep shooting trees and rocks. And if I feel the world is lacking a certain brand of journalism … well, it’s a free country. I can cast my own line.

Whether or not I’ll catch anything remains to be seen. But there are plenty of fish. Some are minnows, some are Leviathans. And it can be really hard to tell the difference.

So stay tuned. I’ll see you in the street.

Max you have never been a trees and rocks kind of guy, not from what I have seen of your work. And that’s a good thing.

But if the world is indeed going to hell, then trees and rocks are bound to come in handy.

Trees and rocks are to Yin as Max photos are to Yang!