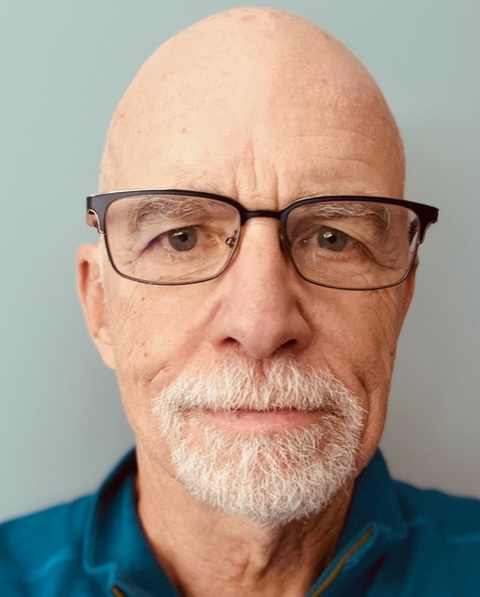

BY BEN BROWN

Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer said something at the Aug. 23 Leadership Asheville Forum that seemed, to me at least, to stake out a position on growth that has heretofore been tough for community leaders to articulate.

Responding to a question from the audience about the prospects for restricting development to protect mountain region aesthetics, the mayor first offered the usual reminders: We live in a state that severely limits municipalities’ regulatory options. And if the question is about safety and stormwater management, there are steep-slope ordinances already on the books. Then, however, came this:

“If you’re saying, ‘Can we put a stop to development?’ no, I don’t think we can do that. Nor would we want to,” said Manheimer. “I think some people would love to just freeze us in a moment in time, maybe 20 years ago. … But cities are either vibrant and growing, or they’re atrophying.”

Beyond factionalism

These are tough times for elected officials. Too many residents have splintered into competing factions, believing we’re being betrayed by those we’ve elected to honor our personal priorities. For some of us, that includes protecting an individual’s stake in the status quo. Under such conditions, it often seems that the best shot at finding common ground is a shared conviction that everything is broken — particularly government.

Little wonder, then, if people whose positions depend upon the consent of the governed are leery of saying aloud that if we want vital, opportunity-filled communities, we have to figure out where and how to accommodate growth and then implement policies and programs at sufficient speed and scale to meet the crises that have provoked this sense of brokenness.

The slow roll of advancing from ideas to action often feels like a no roll. But here’s the good news: It’s getting too late to do nothing.

Any one of the threats currently branded as “existential” — climate change, recurrent pandemics, growing gaps between rich and poor — should be enough to inspire us to come together in aligning purpose and performance. But what’s needed to spur us to meaningful action is not only recognizing looming emergencies but also feeling their impacts in our daily lives. And that hadn’t happened in Asheville until enough people finally got fed up with stepping over sprawled bodies on downtown sidewalks and worrying about how anyone making less than $90,000 a year can afford decent housing here.

One of the key takeaways from the Asheville Watchdog’s recent 12-parter on downtown issues was how housing intersects with public safety, mental and physical health, the tourism economy and a ton of other concerns that we tend to treat as entirely separate matters. Turns out everything’s connected. And housing may well be the nexus that compels us to leverage both this recognition and the opportunities it offers.

One of those critical intersections is with economic development. “We’re for housing, and housing of all types,” Zach Wallace, vice president of public policy for the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce, was quoted as saying in John Boyle’s Aug. 22 piece in the Watchdog series. When the Economic Development Coalition is wooing potential employers, noted Wallace, “One of the things those folks look at is ‘Do I have a workforce there?’ And that workforce needs housing.”

Wallace’s statement resonates like Manheimer’s point about community vitality, but with one critical addition: an implied responsibility to do something about it.

Housing for all

Cutting even deeper is a plan from MountainTrue, one of Western North Carolina’s largest and longest-running environmental advocacy organizations, to add a housing initiative to its to-do list. Better yet, the organization is proposing an answer not only to the “what” question of housing but also to the “where.”

“For starters, we are going to push for policy change that makes it easier to build homes close to our town and city center,” Susan Bean, the nonprofit’s housing and transportation director, explained at the initiative’s Aug. 10 coming-out party.

The logic behind her statement is a case study in “everything’s connected” thinking.

It’s going to take a historic effort to close the gaps in housing supply that are close to the places where people work, shop and entertain themselves and where there may also be options for walking, biking or taking mass transit. But without a keen awareness of both the broader context and the potential for such connections, the current unfulfilled demand will continue to drive sprawl into the car-dependent burbs and beyond, threatening the viability of the very farms, rivers, forests and other areas that MountainTrue works so hard to protect. Redirecting housing demand from urban centers to outlying areas will inevitably mean more and wider roads to accommodate ever more commuter vehicles producing more greenhouse gases; importing more cars into those urban centers will create more congestion and increased demand for daytime parking at higher cost to city taxpayers.

“If we’re willing to share our spaces and invite people to live where roads and schools and stores already exist,” argued Bean, “we’re going to minimize our collective carbon footprint at the same time as we increase demand for things like street trees, sidewalks, bike lanes and public transit.”

Hence, the initiative’s name: Neighbors for More Neighbors WNC, patterned after a Minnesota group with a similar name and mission.

Yes, now

OK, so that’s the Chamber of Commerce and perhaps the most influential environmental organization in the region aligning their goals with a sense of urgency to connect the dots. But there’s a host of other local entities sounding similar notes. Asheville for All proposes YIMBY (yes, in my backyard) advocacy to counteract NIMBY resistance to new development; Thrive Asheville prominently features housing issues on its website. And in addition to these relative newbies, more established groups like Pisgah Legal Services and the Dogwood Health Trust also recognize ways that housing intersects with their respective equity and health care concerns.

So, despite the considerable challenges, maybe the energy is there to move beyond brokenness and toward ways of thinking and acting that acknowledge the mayor’s realism and justify the optimism of folks like Susan Bean.

As Bean explained at the Neighbors for More Neighbors debut, “We want people to understand the impacts of choosing not to welcome new neighbors — the impacts of sprawl and increased carbon emissions and more forests lost. So that maybe the next time a project is proposed in someone’s neighborhood, they’ll be able to think about the benefits that could come from that project instead of fearing a loss.”

Ben Brown is a former newspaper and magazine journalist who recently retired after 14 years as a partner with the urban planning and design firm PlaceMakers LLC.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.