If you ever wonder whether miracles still happen, a drive through downtown Asheville in just about any season or time of day will provide plenty of affirmative evidence.

Many folks who know today’s downtown seem to imagine that in the 1990s, businesses simply moved into old buildings, set up shop and watched the customers flow in. Others mistakenly believe that a small number of affluent, committed white men made it happen. Often when our transformation story is told, the large and distinct role of our city and county governments is minimized or forgotten altogether. This revisionist history is inaccurate, diminishes the true story, and wipes away valuable lessons that we need to remember and others might find instructive.

Mountain Xpress’ focus on the ’90s plucks one decade out of a four-decade revitalization saga. I arrived in Asheville from Cullowhee in 1972. I observed the serious demise of our center city that started when the Asheville Mall opened in November 1973, and I experienced the “ghost town” of the next 15 years or so. I participated in the turnaround of the mid-1980s to ’90s, and I’ve been thrilled by the subsequent growth and vibrant activity. Even during the Great Recession, downtown remained amazingly resilient.

In the 1970s and ’80s, the naysayers’ voices were loud and persistent. Due to previous conflicts and misstarts, few people believed that downtown could rebound. But we did it. Moving from a wasteland of vacant, dirty streets, partial demolitions, lifeless buildings, and adult bookstores and theaters to the “top 10” lists in just about every category is truly a miracle. Our transformation story is multifaceted, wide and deep, and it includes contributions from hundreds of citizens who cared. The following reflections merely scratch the surface.

Roots in the 1980s

The downtown Asheville we enjoy today actually had its roots in the 1980s.

That decade began with a healing period of several years necessitated by numerous failed attempts at downtown revival. A number of forces brought focus again, including advocacy by downtown property owners, visionary Roger McGuire, and nonprofits (Quality ’76, Discovery, the Arts Council and others). A visit to Asheville by Mary Means (founder of the National Trust’s Main Street program) hosted by the French Broad Garden Club and attended by over 500 people was a big impetus. Even a 1980s water agreement (yes!) played a role. These factors drove the Asheville City Council of 1985-86, with Louis Bissette as mayor, to concentrate on downtown and compelled them to hire Douglas O. Bean as city manager in April 1986. Doug’s successful experience in Morganton’s downtown revival, his professional acumen, and his love of downtowns made him the “right-time leader” for Asheville.

Within a few months, Doug began assembling the pieces of downtown’s public/private partnership. City Council appointed a new Downtown Commission with Bob Carr of Tops for Shoes as the first chair. I was hired as director of the new Downtown Development Office, working directly for the city manager. With no private partner available, the Asheville Downtown Association was created and sponsored by the city until it could become self-supporting. The ADA celebrated its 25th anniversary last year. A small staff worked out of the downtown office, and Doug charged every city department with accountability for downtown development.

The engagement of hundreds of citizens began in the mid-1980s through an endless succession of planning meetings, committees, boards, design charrettes, surveys, fundraising efforts, input sessions and volunteer stints for numerous festivals. Amenities that would open in the 1990s were hatched in the late ’80s, including Pack Place Education, Arts & Science Center, streetscape and appearance improvements, and the arts and culture focus.

Three major developers were recruited and incentivized by the city. Thus began an agonizing, long and disruptive construction period that downtown advocates were thrilled to accommodate. Numerous multibuilding projects were simultaneously underway on Wall and Haywood streets as well as along two sides of Pack Square. Public construction projects added to the confusion.

Pivotal decisions were made by the City Schools, county and city government, and some state government departments to keep or locate services downtown. The county’s decision to rehab the Sears building for the Department of Social Services was instrumental. The city’s decision to keep McCormick Field in its historic location and seriously upgrade the ballpark was powerful. Play in the ballpark resumed in 1992. The City Schools leasing administrative space in the Pack Plaza project was significant. These early choices provided an initial core of customers and sent an undeniable signal of support. Another major anchor decision occurred when Tops for Shoes recommitted to downtown and expanded its footprint by several buildings. In the late 1980s a limited number of developers, notably Don Martell, cleared out 40+ years of pigeon guano, cobwebs and dirt to reposition buildings for later development as residences.

As revitalization began in the late 1980s, numerous entities signed on to a comprehensive vision statement that boiled down to this: create an environment where both civic life and commerce flourish.

We spent the late ’80s and all of the ’90s making that vision reality.

Realities and barriers

The environmental context for serious economic restructuring was solid in some arenas, fluid and uncertain in others. Banks and other lenders weren’t favorably disposed to invest in any downtown project — big or small, local or not, construction- or business-related. This meant that owners, investors and developers were self-financing many projects, placing additional major pressure to succeed on the revival’s leaders.

Unlike other states, North Carolina allowed few development incentives and tightly restricted what cities could offer. Within our center city historic district, the federal tax credit was beneficial. Local governments approved local landmark designations that provided incentives for rehabilitating property. Eventually the state added a tax credit that put many buildings in play; this effective job generator was scuttled in 2014 by the General Assembly. Accepting these benefits required developers to incorporate high quality design standards.

These barriers left downtown dynamics conflicted and unpredictable. The Schneider Group’s huge private project framing two sides of Pack Square totally stalled in 1987 when the developer went bankrupt. Ted Prosser stepped in and finally secured financing through the Bank of Scotland. Renegotiating this complicated public/private deal took a week and occupied three floors of the City Building. On Nov. 4, 1988, the closing documents were recorded and this significant project was revived.

The residential construction now underway on “The Block” (the Eagle/Market streets area) was at least 25 years in the making. Years earlier, the preservation of the YMI building had provided a significant anchor. Subsequent developments and improvements were planned, then lost support; refinanced, then saw interest wane; federal grants were secured, then local agreements were scuttled. Yet despite all these trials and travails, the revitalizing spirit prevailed. Meanwhile, across town, the Grove Arcade project spanned at least 10 years, with numerous ups and downs involving the federal government, investors, the city, other downtown businesses, donors and the lead nonprofit. But the arcade, which reopened its doors in late 2002, recently celebrated full, solid occupancy!

Creative solutions

One action taken by the city in the late 1980s cost almost nothing yet generated thousands of hours of enjoyment and hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales: an ordinance allowing outdoor dining, street vendors and entertainers on city sidewalks. As more people began taking advantage of those opportunities in the early 1990s, it helped create surprises and the Asheville vibe. Remember enjoying a glass of wine and a nice meal at Café on the Square under the stars?

Pack Place Education, Arts & Science Center was envisioned as a center city entertainment and educational hub, pulling together several small museums then scattered around the city and adding a new theater. The high-profile Pack Square location donated by the Schneider Group was perfect: The idea was that these public entities would work together closely, creating joint program offerings, attracting upmarket traveling exhibits and integrating programming with the state’s school curriculum. But the needed collaboration proved challenging from the start.

Led by the indefatigable Roger McGuire, however, early volunteers known as the Pack Rats worked diligently over several years to drum up private funding for this huge project. Arts Council Director Deborah Austin and the Downtown Development Office provided staff support in the early years; a bond issue approved by city residents and annual county allocations provided key public support. And even as major hurdles arose and dollars became harder to find, these volunteers raised $12 million — the most by any Buncombe County capital campaign at that time.

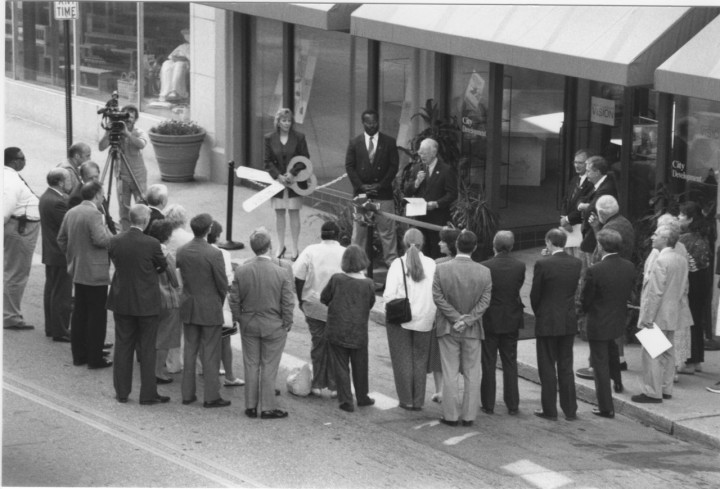

When Pack Place opened its doors on July 4, 1992, it was a glorious day for downtown Asheville.

Determined downtown advocate, resident and investor Julian Price was involved in numerous projects behind the scenes. Julian came to Asheville in 1990, in part because by then he could tell we were serious about our commitment to a thriving downtown. Smart investments that others couldn’t or wouldn’t make, he realized, could have a considerable positive impact on downtown. Public Interest Projects Inc., the for-profit development company he founded, successfully tackled a variety of projects; Julian also took a vocal interest in pedestrian issues.

We learned early on that despite low usage of the Civic Center parking deck and ample street parking, more facilities were necessary to attract development activity. In addition to the federally funded deck built as part of the Pack Plaza project, two more, on Rankin Avenue and along Wall Street, were funded using revenue bonds. Squeezing these facilities into the existing landscape proved extremely difficult and contentious, especially on Wall Street. In the summer of 1988, Ashly Smith Maag’s internship project was to count and record downtown parking spaces. In the ’90s we overlaid that data on a scale map of the Asheville Mall, proving that mall patrons walked much farther than people visiting downtown stores — and refuting the “It’s too far to walk” argument. City Council’s courageous investments in parking incentivized development in the 1990s, and profits from the two decks still owned by the city fund other urban-related projects today.

As the 1990s got rolling, the various complicated projects, testy political dynamics, policy conflicts and glimmers of downtown’s potential collided head-on. Amazingly, small businesses such as The Market Place restaurant, The Chocolate Fetish, the Haywood Park Hotel, PARSEC Financial Group, Northwestern Mutual Insurance and The Bier Garden began filling the newly rehabbed spaces.

Infill projects were equally important. On Biltmore Avenue, John Cram saved four buildings and now we enjoy the Fine Arts Theatre,Bellagio,Blue Spiral 1 gallery, Avaloo and Olive & Kickin’. Across the street, theMast General Store in the former Fain’s Thrift Store building is one of the busiest spots downtown.Salsa’s, which grew out of a tiny storefront taco shop, was an early and tasty success.

Most of these projects applied the historic preservation standards required for federal tax credits and promoted by the Downtown Commission and City Planning. But compliance was not required, leading to today’s eclectic look.

The city renovated a building on Haywood Street, giving our office a street-level home while providing a walkway between Haywood Street and the new Rankin parking deck. This project boosted businesses and increased our office’s productivity and visibility.

Asheville’s renown as a beer destination got its start downtown. In the early ’90s Oscar Wong asked the Downtown Commission for a conditional use permit allowing him to make beer in the central business district. Although skeptical of his basement endeavor, the commission approved the permit. Oscar’s brews, first available on tap at Barley’s upstairs, are now sold in nine states.

Festivals and special events were a central downtown marketing strategy to build awareness and sales. The ADA and the Downtown Development Office produced a steady stream of diverse events, such as: First Night Asheville (a ticketed, nonalcoholic New Year’s Eve party); Downtown After 5 (still going strong); Oktoberfest (now enjoying a renaissance); Light Up Your Holidays (a monthlong celebration with white light decorations throughout downtown); Tell It in the Mountains (captivating stories); Gallery Crawls throughout downtown; and Independence Day fireworks and activities.

In the ’90s, the Bele Chere festival expanded rapidly, generating a substantial countywide economic impact each year. (A 1994 intercept survey pegged that year’s number at $10 million — $16 million in today’s dollars.) After the festival was discontinued last year, some claimed that its sole intent was to facilitate downtown revitalization, but by the 1990s, the city viewed its support as an investment in countywide business activity. The festival’s impact was felt far beyond downtown: Roughly half of those attending were from Western North Carolina. Realizing the event’s broad regional impact, the Bele Chere board, under the leadership of Jim Daniels, adopted the tag line “A Community Celebration in Downtown Asheville.” Bele Chere incubated numerous businesses, was a training ground for hundreds of volunteers, offered fundraising opportunities for local nonprofits, and provided a free opportunity to gather in the community “living room” and have fun.

Numerous streetscape and landscaping projects were another focus in the ’90s, planting trees and significantly improving lighting, street furniture and cleanliness. Pritchard Park finally stopped serving as a bus depot when the city built the Coxe Avenue transit hub, opening the door for the subsequent park overhaul. And in the latter ’90s, initial planning began for what are now Pack Square Park and Roger McGuire Green.

Perseverance through adversity

Despite these achievements, in the early ’90s political support for downtown grew fractured and contentious as jealousies arose over power, leadership, priorities, wealth and recognition. The Downtown Development Office began working in other commercial districts, especially West Asheville and Biltmore Village, to help them benefit from downtown’s lessons. The Council of Independent Business Owners emerged, City Council’s makeup changed, and these conservative voices expressed dissatisfaction with downtown’s progress (after only seven years) and the amount of public money spent.

During the 1993 City Council race, there was no mention of City Manager Doug Bean’s performance, yet five minutes after being installed, they fired him on a 4-3 vote. Council members Gary “Rock” McClure, Carr Swicegood, Herb Watts and Vice Mayor Chris Peterson voted to fire Doug; Mayor Russ Martin, Leni Sitnik and Barbara Field opposed it. No one who was there will forget activist Minnie Jones, the last speaker in a three-hour hearing, telling Council, “You’ve done tore this town up.” The crowd erupted in cheers, and Minnie’s prediction proved true. Doug became director of the massive Charlotte-Mecklenburg Utilities District and completed his career there. A large but unsuccessful campaign sought to recall the Council members who’d voted to fire Doug; all four lost their seats in the 1995 election. Most of the city’s management team departed over time, and the turmoil negatively affected downtown’s development momentum for several years.

City Manager Jim Westbrook, hired after the 1995 election, promptly dismantled the Downtown Development Office. After 10 years, I left city employment on Bele Chere Sunday in 1995, and the services the Downtown Development Office had provided were never fully replaced.

Despite political distractions and their serious implications, volunteer-led projects continued to thrive. The Asheville Urban Trail, launched in 1991 with a design charrette including citizens and diverse professionals, was another strategy for making downtown a compelling urban space. Year by year, 30 stations were installed, using public art and narration to tell fascinating mini-stories about Asheville along a circular 1.7-mile route.

Grace Pless was the guiding spirit of an intrepid volunteer committee, and the challenging project was staffed by our office with great support from many other city departments. Volunteers raised over $1.5 million for the stations, and researchers, landscape architects, writers, contractors, artists, architects and historians contributed thousands of pro bono hours. With its turkeys, pigs, cats, Wolfe’s shoes, the treasured little girl and more, this beloved civic amenity is yet another example of the public/private partnership model we repeatedly used downtown.

Meanwhile, the Downtown Association organized property owners, small-business owners and residents; marketed downtown as a viable business district; led joint sales campaigns; published and widely distributed downtown news updates, and ran a “myth busters” campaign to combat misinformation continuously released by detractors.

Throughout the turbulent 1990s, many decisions were made about investments, policies, events, leadership and design. And though we tried to rely on proven techniques, we were also conscious of the need to retain Asheville’s funky personality; encourage assorted options in food, music, retail and entertainment; use diversity and local talents to our advantage; and ensure that those decisions were realistic, commercially feasible and distinctly Asheville.

Achievement examples

It was thrilling to watch locally owned businesses such as The Laughing Seed, Climbmax, Gentleman’s Gallery, Jewels That Dance, Laurey’s, City Bakery, Beads and Beyond, Vincenzo’s, Dancer’s Place, Wick & Greene Jewelers, Ms. G’s Barber and Beauty Salon, Bloomin’ Art, Malaprops, Loretta’s and Appalachian Craft Center grow and succeed. Informal yet effective local mores discouraged chain restaurants and retail from locating downtown.

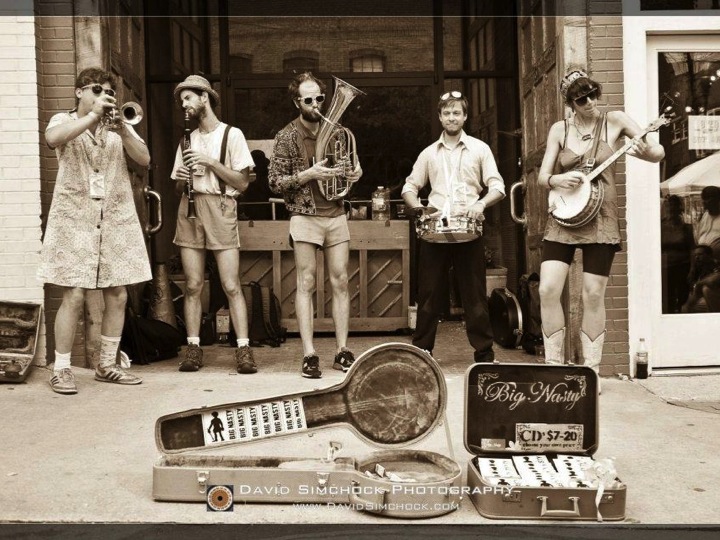

An important force in downtown revitalization was the numerous arts, civic, religious and social offerings that remained or relocated there. The churches were a constant generator of traffic and goodwill. The creation of Jubilee! Community on Wall Street certainly sparked new believers in downtown. The Asheville Community Theatre, HandMade in America, Asheville Symphony, Shindig-on-the-Green, Be Here Now, buskers, various Civic Center events and other entertainment all helped create a pulsing, effervescent atmosphere.

Organizations such as the Junior League of Asheville, the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce, The Community Foundation of WNC, the Preservation Society, Trinity Place, Quality ’76 (now Asheville GreenWorks), the United Way, ABCCM’s shelter and numerous others invested in downtown while providing access points for important public offerings and services.

Here are a few measures of success during that period:

- State records show that from 1976-2003, 135 income-producing buildings — almost all of them downtown — were rehabilitated using federal and state tax credits. That was 15 percent of all such projects in the state, and the most by any county, in those years.

- Asheville’s central business district generates by far the highest percentage of total property tax revenue among North Carolina cities, when land area and real estate value return are considered.

- Data gathered several years ago showed that Asheville’s CBD contributed almost $6 million to city and county coffers: the fourth highest total in the state.

- In 1982, the total value of property in the CBD was $48,237,500. In 2004, after more than 20 years of concerted work and tens of millions of dollars of private investment, the taxable value was $386,834,500: a 702 percent increase. This relieved tax pressure on residential properties.

- Downtown’s resurgence helped achieve higher bond ratings for both city and county government.

Unsung heroes

As time progresses, it’s clear that one element set our rejuvenation story apart: civic engagement. A major objective of the Downtown Development Office was to continually involve many diverse participants in meaningful roles. When you’re involved, you care. You pay attention. You advocate. You shop. This approach helped sustain the initiative long enough for the change process to take hold, especially when the political winds shifted. Leadership skills gained downtown were transported all over the community and benefited numerous causes.

We hear a lot about what a few individuals did, and they did a lot. But this small hard-working group could never have achieved such deep social and economic change. I salute the unselfish legions of believers and hard workers who were instrumental in creating this amazing urban transformation story.

These staff, who served at various times in the Downtown Development Office of the 1990s, deserve recognition and thanks:

Rita Baidis

Terry Clevenger

Curt Crowhurst

Pat Davis

Mary Haynes Fierle

Karen Hultin

Karon Korp

Ashly Smith Maag

Jean McQueen

Trina Royer

In retrospect, perhaps the most significant achievement of the 1990s was resilience: successfully sustaining many substantial initiatives, navigating the nasty conflicts, making downtown interesting again, creating enjoyable and useful volunteer opportunities, and continuing to plan, build and co-create the district piece by piece. Downtowns are never “finished”: Although there were excellent outcomes in the ’90s, they only hinted at the future potential and joy of a unique, captivating, fun space that also succeeded in becoming Western North Carolina’s economic, social and governmental center. We knew then that an achievement of this magnitude, won over many years by thousands of players, would leverage other momentous civic and economic achievements in Buncombe County and beyond. The rest of this story proves that our bold, smart, hearts’ desires were right: Downtown is now a true miracle.

Leslie Anderson served as Asheville’s downtown development director and then city development director from 1986-95. She’s now president of Leslie Anderson Consulting.

Brilliant article Leslie, comprehensive, insightful … and a nice trip down memory lane!

Excellent article!Leslie Anderson is certainly an “unsung heroine” of Asheville’s history!