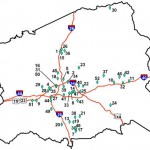

- Listed but languishing: Since 1987, the state’s Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch has cataloged 50 sites in Buncombe County alone. map courtesy GL Mapping Services

- Worrisome signs: Toxic materials including lead, mercury, asbestos and DDT have been detected in soil and stream samples at this dump site in Swannanoa. photo courtesy N.C. Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch

- Slow burn: An abandoned incinerator in Swannanoa once used by the Army’s now-demolished Moore General Hospital is a suspected source of hazardous contamination. photo courtesy N.C. Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch

In a wooded corner of the state Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s facility in Swannanoa sits a derelict incinerator overgrown with vines; an open door reveals piles of ash within. Corroded metal containers and other solid waste protrude from the ground nearby, murky puddles collecting in their partially submerged forms.

A cross-country trail used by the Owen High School track team skirts the site’s perimeter fence. The Swannanoa 4-H Center hosts a summer youth camp on an adjacent property to the north. Yet little is known about what dangers may lurk in this decades-old hazardous-waste dump, used by the since-demolished Moore General Hospital during World War II.

One of 50 such identified trouble spots in Buncombe County (see map), it came to the attention of the state’s Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch in 2008, when a caller described some suspicious-looking material near the detention center’s property line. The following year, the environmental agency removed eight discarded transformers from the site. Two of them were leaking PCBs, which are persistent organic toxins. Other partly buried solid wastes, including paint and pesticide containers and construction debris suggested the need for more extensive assessment; preliminary tests indicated the presence of heavy metals in the soil and DDT in the stream sediment. But with so many problem areas waiting to be addressed, the state simply erected a 6-foot chainlink fence and posted warning signs to deter unauthorized visitors.

“I’ve got so many sites, like all my co-workers; it’s this way in every county,” project manager Collin Day reveals. “I could spend all my time on just one county — especially if they were all of this magnitude.”

Despite the considerable publicity in recent years concerning the abandoned former CTS of Asheville plant on Mills Gap Road, few area residents are aware of how many other such sites exist in Buncombe and surrounding counties — and how little is being done about them.

Since its creation in 1987, the Hazardous Sites Branch has cataloged 2,982 such places statewide — and there’s no telling how many others remain to be found. Of the known sites, 85 percent still languish, with any hope of cleanup (assuming this even proves feasible) deferred to some ill-defined future. Meanwhile, contamination may continue to spread, further jeopardizing the health and well-being of unsuspecting neighbors.

Deadly orphans

After an initial assessment revealed high levels of asbestos, lead, mercury and other hazardous elements in the soil at the incinerator site, the state agency — an arm of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ Division of Waste Management — fenced off a larger area this fall. Yet little is known about the extent of the contamination.

“The next phase will be to investigate the ground water and the stream out there,” Day explains, installing wells “to determine how much of this may be flowing off-site.” No one in the area is known to be using well water, he reports. “Once we got the fence up and got the transformers out of there, there was breathing room. Now we’ve got it isolated from the public; now we can get to the science of identifying and cleaning this stuff up.”

Judging by what’s happened with the CTS site, however, Day’s assessment may be optimistic. First brought to the state’s attention in the late 1980s, both the CTS property and neighbors’ wells have been repeatedly tested and found to be severely contaminated. Yet to date — and despite the involvement of federal and state agencies — nothing remotely resembling a full cleanup has been done, and there seems little reason to expect such action in the near future (see “Fail-safe?” July 11, 2007 Xpress, and related documents at mountainx.com/xpressfiles/040908ctssite).

The state created the Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch to evaluate and manage sites not covered by other programs. (In this context, “inactive” means no other entity is issuing permits or overseeing a cleanup — see box, “Hazardous Wastes 101.”) Many types of hazardous releases are regulated under other laws, such as the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act or the Clean Water Act.

The state agency, however, is woefully underfunded and understaffed. Last year alone, its budget was cut by an estimated 65 to 70 percent, according to the branch’s annual report to the state Legislature, and this year’s looming fiscal crisis appears to offer little prospect of even maintaining the current level of support.

One group of hazards the branch works with are those associated with “orphan” (i.e. unpermitted, unregulated) landfills, particularly ones that closed before 1983. Predating today’s federal regulations and often lacking adequate post-closure monitoring, these sites don’t easily give up their secrets. Their toxic substances may be buried underground or screened by vegetation; unseen, they may nonetheless contaminate ground or surface waters or expose neighboring residents to toxic gases, which can even penetrate adjacent structures through the foundation.

How do you spell “success”?

Two of Buncombe’s listed inactive hazardous sites, both in Asheville, are former coal-gas plants. “It was the country’s first utility, really,” Patrick Watters of the Inactive Sites Branch explains. Operators “would take coal and heat it in the absence of oxygen, a process called pyrolytic heating, driving off the volatiles, which would be collected in cylindrical tanks [to be used] for lights, heating and so on.”

The resulting coal-tar byproducts were either resold or abandoned as hazardous waste, Watters reports. Both Asheville properties have been investigated, he adds: “One site [at Martin Luther King Drive and Valley Street] did not require remediation, but the river site [on Riverside Drive] did. Excavation removed a great deal of the source material that was left behind, plus underground structures.”

The state also imposed deed restrictions limiting how these properties can be used in the future and requiring long-term ground-water monitoring — “first on quarterly intervals; now just two times a year, as [contaminant levels] have stabilized.” Watters says the state considers these sites success stories.

But they are evidently in the minority. In 1997, significant contamination was found at the former Hyman Young Greenhouse on Cedar Hill Road, both in soils on the property and in a neighbor’s well. Pesticides, heavy metals and trichloroethylene (an industrial solvent that is one of the primary concerns at the CTS site) have been identified along with evidence of a sizable fuel-oil spill. After the responsible party declared bankruptcy around 2004, the state hired a contractor to conduct ground-water recovery and treatment. Referred to the Inactive Sites Branch in 2007, the property is still awaiting a complete assessment.

At Smoky Mountain Machining Co. on McIntosh Road, the state’s Hazardous Waste Section attempted to clean up contaminated soil sometime before 1995, according to project manager Bobby Lutfy. More recently, however, trichloroethylene was discovered in an on-site drinking-water well.

Another site, the former Ticar Chemical Co. property in south Asheville, has had at least three sizable spills since the mid-’80s. In 1986, volatile organic compounds were detected in sediment samples and in an on-site drinking-water well.

A state contractor began corrective action in November 2001, including soil removal, soil-vapor extraction and a pump-and-treat ground-water system. “While there has been some improvement of contaminant conditions at the site, current monitoring indicates continued remediation is needed,” Lutfy reports. According to state files, however, neighboring residents are on city water.

A political issue

Meanwhile, back at the CTS site, “We’re in the middle of a ‘phase II’ assessment to determine the extent of the pollution,” says project manager Bonnie Ware. The agency is working to “characterize the hydrology of the site to determine the ground-water dynamics and the full extent of the plume,” she explains. “Then comes the phase where they develop a remedial strategy for cleanup. It can take awhile sometimes.”

Ware adds: “I’ve got a mountain of data to go through right now. They’re installing more wells away from the site on private property.” After the monitoring wells are installed, “If one comes back with contamination, we’ll have to step outward again. Once you find clean ground water, there’s a statistical process for determining the shape of the plume.”

Monthly updates are supposed to be posted on the agency’s website, but at last check, the most recent report was from August 2010. “We’re grossly understaffed,” Ware says with a sigh. “The state gives us our budget. … As to why there aren’t more people assigned, I guess that’s a political issue.”

Overwhelmed and underfunded

The Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch has guidelines for assessing and addressing the properties on its list, and it allocates its meager mitigation dollars according to the threat each situation appears to pose to human health, gauged primarily by proximity to known drinking-water wells. If there aren’t any nearby, Ware explains, the agency has little choice but to let a potential hazard languish, regardless of how little may be known concerning the extent of the problem. Eleven of the 50 Buncombe County sites on the inactive list have been designated “no further action,” but this does not necessarily mean the problem has been solved.

“We have more than we can handle with our high-priority sites,” notes Bruce Parris, the agency’s western regional supervisor. “There are an awful lot of sites that are sitting out there without direct oversight right now. We’re only addressing the sites where there are major issues that could impact public health. The others we’re trying to funnel into the REC Program.”

That would be the state’s Registered Environmental Consultant Program, in which approved private-sector consultants can certify compliance by property owners who are having their hazardous sites cleaned up at their own expense. The Square D electronic components plant on Bingham Road in Emma is being evaluated for the program after soil and ground water there were found to be contaminated with petroleum, PCE, TCE and chloroform. In 1994, an underground remediation system was installed to extract and treat ground water, using a complex and time-consuming process known as “air stripping.” As with the Ticar site, active remediation and monitoring are continuing at Square D, according to Lutfy.

In the state’s eyes, getting Square D into the REC program would qualify as a success story. But Weaverville resident John Payne doesn’t think much of the agency’s modus operandi.

“‘No known water-supply wells’ — that’s what they said about CTS,” asserts Payne, several of whose relatives live near the Mills Gap Road site. Payne says his cousin Bobby Rice, who lives next door to the shuttered facility, “was poisoned” by contamination in the family’s spring, where the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency later found trichloroethylene at 21,000 parts per billion — more than 4,000 times the “safe” standard for drinking water.

What’s a neighbor to do?

If the agency tasked with overseeing assessment and remediation of hazardous sites seems too underfunded and distant to have much effect, could a local entity do a better job? The Buncombe County Health Department does have an Environmental Health Division, but it focuses on things like permitting septic systems; inspecting restaurants, lodgings, swimming pools and day care centers; and preventing childhood lead exposure.

And though the files of the Inactive Sites Branch are open to anyone, citizens wanting to know more than the names and addresses (which are available online) may have to travel to Raleigh. Meanwhile, the agency’s already overworked staff must field hundreds, even thousands of such requests each year, typically when an industrial property changes hands and a potential lender seeks certification as a hedge against an expensive future cleanup.

But that hasn’t stopped citizen watchdogs like Payne from asking pointed questions. “I’ve always had the concern about these sites,” he notes. “People are punching holes in the ground and dumping whatever” — a situation he finds particularly worrisome in view of Buncombe County’s estimate that up to half its residents drink from wells. At one unregulated site on Hollywood Road in Fairview, for example, “People would come there and dump anything … paint cans, solvents, you name it,” Payne recalls.

His fears appear well-founded. According to the Inactive Sites Branch’s most recent report to the Legislature, most of these older, unpermitted landfills have probably leached hazardous substances into ground water. What’s more, the report notes, 77 percent of the ones inspected lie within 1,000 feet of a house, school, day care center, church or drinking-water source.

Meanwhile, even the most persistent citizen activists must confront a baffling network of overextended, overlapping bureaucracies; defunct businesses; current businesses resistant to accepting responsibility; conflicting political pressures; protracted legal battles; and, ultimately, the high cost of even attempting to eliminate long-festering contamination that may be continuing to spread.

The sheer number of hazardous sites in the community indicates the need for due diligence, notes David Gantt, chairman of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, who passes the shuttered CTS plant every day on his way to work. But when it comes to cleanups, he points out, “The county’s role is limited — it’s a state or federal issue. We know there are other sites, but [remedial] action is out of our jurisdiction.”

With CTS, says Gantt, “I wish there had been a lawsuit early on, with people speaking under oath. … It’s frightening to me that we could let regulation get so slack and lax that something like this could happen.”

For CTS neighbors such as Dot Rice (Bobby’s wife), the situation is beyond frightening. “It has really destroyed us — financially, mentally, physically, everything,” she says. “We were going to sell our house, retire somewhere else. … It is so stressful and so disheartening.”

As for public agencies, she observes, “Their job was to protect us, but they haven’t done that. I just pray every day that it’ll get cleaned up, and that other people won’t have to go through what we’ve been through.”

— Susan Andrew can be reached at 251-1333, ext. 153, or at sandrew@mountainx.com.

Is there a map available, anywhere, that shows contaminated areas in Asheville?

All this sounds like the 60’s in Europe, or a current story from the last remaining “third world countries”.

Also: I’m wondering, how many “organic” farmers grow their food (unknowingly) grow and water their crops with contamination carelessly left behind.

The map in the click-through set of images in the box above displays just the sites catalogued by NC’s Inactive Hazardous Sites Branch (part of DENR’s Division of Waste Management). Those are sites where no state or federal authority is actively engaged in permitting, cleanup, etc. In addition, you may wish to view sites where hazardous releases are occurring, with state-issued permits under the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts (or other laws); to see where those sites are, you can log on to the EPA’s mapper at http://www.epa.gov/emefdata/em4ef.home

Thanks for focusing attention on this problem. It’s painful to witness a nation that is willing to spend billions on unnecessary wars while defunding hazardous waste cleanup on sites that are killing our citizens. Our political priorities are completely screwy.

By the way, readers/viewers: If you have (or think you have) information about contaminated sites in the Asheville area, please send your tip to news@mountainx.com.

We’ve had some submitted posts to that effect, but can’t allow them through without investigation, corroboration, etc.

Yes, Cecil our priorities are screwed when we buy land for a park, build sidewalks through solid rock (Patton Ave) and let CTS exist. I found in interesting that Martin Luther Drive area would have a problem.

David who knew all along about the dumping at the CTS site? Isn’t there some kind of oath of office that covers such misbehavior? I have been telling you guys about this since 1999.

Thank you Susan for this great article. I tought the environmental situation in Asheville and sorrounding lands would be better than those in Nicaragua where I am from originally, but seems it is in a similar situation. It is sad to confront the reality of pollution impact and government underfunding / understaffed in this area… same in Nicaragua. By the way, those haz-waste sites you mentioned are the remanents of the past people efforts to develop United States. I am confident the state cleaning up efforts will continue and only new clean industrial process will be allowed to be stablished in Buncombe County. My hypotesis is that most of the new generations of professionals and business men are now building a better future for USA, we don’t know if this hypotesis is valid for North Carolina and for Bunconmbe County. Validating this hypotesis could be also the source for another article and could give a light to improve the situation. Every year new groups of natural resources conservation students graduate from UNC-Asheville and new environmental engineers also graduate yearly from Duke University. And there are many more environmental educational centers around. Where those professionals go? Are they engaged in building a better green and sustainable future for new generations? What is their job reality? How can we improve their action? Same with business professional, are they applying industrial green proceses? Thanks.

Excellent perspective, Carlos.

A Triple Bottom Line approach to business is needed. What you are asking for, it seems, is a national TBL Audit.

There is no coordinated National TBL mandate, at least in the US. It’s all voluntary. I think some voluntary and some mandated TBL best practices will lead to significant innovation. That’s the other key term: innovation.

Innovation means creative solutions, but also the business (or government) management, mechanisms and financial injection to make the change happen.

At the same time unethical negative anthropogenic innovations (as we now understand them) have created our more dangerous social, environmental and economic risks. The list there is too long to inventory here, but suffice it to say, the flow of human waste being forced on all of us, even folks who think the garbage we sell each other and put forward as public policy (in too many cases) has not been stemmed and reversed at this date.

SOME businesses are adopting genuine, positive ethical TBL innovations. Since none of this is ubiquitous, as of yet; and not even all our local, state, and Federal government agencies and politicians are on board, this kind of innovation needs more support to get the job done and mitigate the laundry list of challenges we face.

Let’s hope 2011 is the turning point! Of course that’s another interesting term: hope. Hope is good, but it’s not positive ethical innovation.

The article states “Cleanups are funded by fees levied by polluters;….” It’s my understanding that this is no longer the case and that taxpayers now foot the bill. Here’s a link with more information:

http://www.martenlaw.com/newsletter/20090422-superfund-tax-reinstated

OOPS! I meant to say the article states “Cleanups are funded by fees levied against polluters;….” not “by polluters.” Sorry.

Thanks, Stewart. I missed that! (fees levied against polluters vs. levied by polluters).

Does anyone know where the former Hyman Young greenhouse is on Cedar Hill Rd.? Maybe the address or what it is beside now?

Great article and thanks for highlighting a serious but completely overlooked problem. In the last year the French Broad Riverkeeper program at the Western North Carolina Alliance has made investigating these sites a priority. We hope to make some significant progress in the coming months and year to answer some of the questions that Susan has posed. Feel free to email us with any questions or concerns. hartwell@wnca.org.