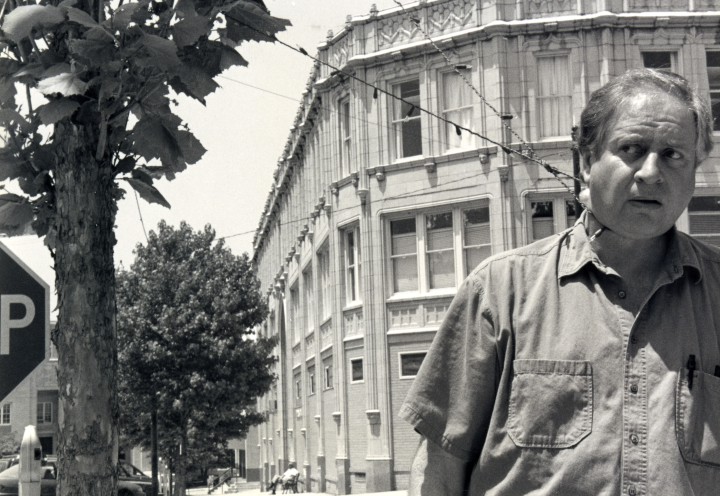

Julian Price paused at the corner of Walnut and Haywood streets. To his left stood the former Asheville Hotel, to his right the old J.C. Penney building. It was 1989, and both structures were boarded up and vacant, as were many of their neighbors. It had been over 15 years since the Asheville Mall opened, but downtown’s barren streets and empty sidewalks still testified to the flight of the major chain stores to Tunnel Road.

To the east, however, framed by the buildings between which he stood, Price could make out the Beaucatcher cut. Perhaps it was the devastated mountain, or a sense of downtown’s unrealized potential, that hit him so hard. Maybe it was neither, or a combination of the two. Whatever it was, Price wept, overcome by a sense that he needed to move to Asheville.

He’d spent the previous two decades in Oregon and Northern California. By 1989, however, the native North Carolinian had decided it was time to come home — just not all the way home. Born and raised in Greensboro, Price wanted to maintain some semblance of the anonymity his time out West had provided, which he knew his hometown could never offer him.

In Asheville, Price tried to fly under the radar as much as possible. But when you contribute nearly $10 million of your personal wealth to help revitalize a long-neglected city, folks are bound to take notice.

Of course, standing at the head of Walnut Street that day, Price couldn’t have known the extraordinary impact he would end up having on his adopted home. Nor could the 48-year-old have imagined that he had less than 12 years to live.

It’s now nearly 15 years since Price’s death. And while many local business owners and nonprofits nod knowingly upon hearing his name, most Ashevilleans remain unaware of his extensive contributions. That’s no fault of their own: It was part of Price’s design all along.

His family and friends, though, are hoping to change that. The Julian Price Project aims to both honor and shed light on one of Asheville’s remarkable modern-day pioneers — a man who, no doubt, would have cringed at the very notion.

The early years

Born June 4, 1941, to Ralph and Martha Price, Julian was the second of three children. Named after his grandfather, who was president of the Jefferson Standard Life Insurance Co., Julian inherited not only this man’s name but a portion of his considerable wealth. And though that legacy ultimately proved to be a blessing for both Julian and Asheville, those who knew him best say he struggled with it for most of his life.

Growing up, “Most of the people he knew were not rich,” explains Elizabeth Spinner, a lifelong friend of Julian’s. Because of this, says Spinner, “He always had to wonder, is this person being friendly just because I have money?”

Julian’s relationship with his mother, continues Spinner, also contributed to his ambivalence about wealth. Martha Price “did not come from a rich family, and it seems to me she always encouraged all her children to associate only with people as rich as they were.” At times, says Spinner, Martha actively discouraged emerging friendships between Julian and children whom Martha felt were below the family’s social class. Julian, of course, resented this.

In 1963, however, Martha died in a car accident at age 54; Julian was only 22. Three years later, his brother, Clay, died of a brain aneurysm. Clay, too, had been “driven crazy by all the people coming at him for money,” remembers Spinner.

In 1967, Julian married a woman named Barbara; the following year, their daughter, Rachel, was born. Within two years, the family headed west, after a brief stint in Boston. Many of those who were closest to Julian say the move reflected a desire to escape the baggage that came with being a Price in Greensboro. “It was … very, very hard for him [to have] people … see him on the street and know that he was Julian Price, the rich white guy,” says Meg MacLeod, Julian’s second wife.

Spinner, meanwhile, says: “Julian was always a non-snob, let me just make that very clear. In no way,” she stresses, did he feel “that his money made him socially superior to anyone.”

Shortly after Julian and Barbara arrived in Oregon, their marriage ended, and Julian made his way down to Northern California. Throughout his time there, he pursued various passions, growing and selling organic vegetables, working at a photo lab and running his own radio program, which focused on issues ranging from racial injustice to gun control to forest and farmland conservation.

Rachel Price notes another of her father’s many interests and talents: mock interviews that he would film, first on a Super 8 camera and later on a VHS Camcorder. “He could be very, very funny,” she recalls, remembering the silly questions he would pose to her on camera.

While still in California, Julian and a friend created a column for a local paper in San Rafael, the Marin County seat. Each week, “Question Man” posed a different query to strangers on the street: “Did you ever know a cruel person?” “Have you ever been betrayed?” and so on. People’s photos were printed alongside their answers.

Every column, however, included Julian’s own answer, flanked by a photo of a tanned, bearded, middle-aged man with a warm smile: “Julian Price, 47, radio producer, San Rafael.”

In response to the question “What did you finally give up on?” he replied: “Being shorter. I always wanted to be 6 foot 2 instead of the 6 foot 5 that I am. Lately, I realized that I just wanted to be less visible, to blend in more. Now I’m glad I’m tall. But I’m also glad I’m not 6 foot 8, because then I’d have to duck going through every door. I hit my head enough now as it is.” The answer showcases Julian’s sense of humor, but it also reveals his lifelong quest to keep a low profile.

After Rachel enrolled in college, Julian’s thoughts turned to North Carolina. “I think he wanted to make a fresh start,” his daughter says, “to feel like he was sort of going back home but not completely.”

Julian’s return came shortly after his father’s death. Like his son, Ralph Price was more interested in people than in business. He briefly took over Jefferson Standard after his own father died but left the company within four years. According to MacLeod, Julian said his father spent time abroad, urging world leaders (including Indira Gandhi) not to use nuclear weapons. Spinner wonders whether Ralph’s death was a factor in Julian’s decision to come back East. “Maybe he didn’t want to be more effective in the world when his father was alive,” she suggests.

Within the year, Julian had moved to North Carolina. “I think when he got to Asheville,” says MacLeod, “he’d reached a place in his life where he could come back home.”

But if Julian’s return was a symbolic gesture of self-acceptance, it was also the start of a campaign to erase his past. To accomplish this, he began writing checks to bolster the efforts of local nonprofits and entrepreneurs. They weren’t investments — at least, not initially. Price was simply giving away his money, in an effort to help a community grow while relieving himself of the guilt and uncertainty he’d always felt about his wealth.

Cutting checks

At first, Julian simply walked the streets of downtown Asheville, armed with an inquisitive mind and an open checkbook.

“He was definitely informal in his approach,” remembers Mountain Xpress Publisher Jeff Fobes. In 1989, Fobes was running Green Line (a monthly precursor of Xpress) when Julian “just popped in.” After talking for a while about the publication’s goals, Julian asked if some money would help. “I believe it was in the sum of $20,000,” Fobes recalls. “My eyes kind of popped, and I said enthusiastically, ‘Yes, I think that would help.’” Julian returned an hour later with a check.

Those impromptu contributions continued throughout Julian’s early years in Asheville. Beneficiaries included the Mountain Microenterprise Fund (now Mountain BizWorks), the Affordable Housing Coalition and the Western North Carolina Regional Branch of the Self-Help Credit Union.

In 1990, Self-Help was a two-person operation tucked away in an upstairs office at 12½ Wall St. Once again, Julian arrived unannounced. Upon entering the tiny workspace, “He basically looked like, ‘This is it?’” says Beth Maczka, who was then the local branch’s director. “He had clearly done his homework, though.” Julian was interested in community banking and appreciated Self-Help’s focus on folks who couldn’t get a conventional bank loan. At the conversation’s end, he made out a check for $100,000 — the federal limit at the time.

“That was the largest check we’d ever received,” remembers Maczka.

Julian subsequently met numerous times with Martin Eakes, co-founder of the local branch’s parent organization. Those conversations, says Maczka, helped Julian see that “when you invest in these old structures, it can anchor community.” He ultimately donated $1 million toward renovating the historic Public Service Building on Wall Street, enabling numerous nonprofits to rent affordable space there, share resources and work together. “Without that contribution,” she says, “that building would not have been renovated.”

But when someone starts spontaneously handing out large sums of money, word gets around. Seeking to dodge the spotlight, Julian approached Pat Smith, executive director of the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina. Another $1 million donation created the Dogwood Charitable Endowment Fund, which makes grants to organizations supporting sustainability and pedestrian improvements, as well as those assisting low-income people. Despite this considerable largesse, however, Julian still felt uneasy. His inheritance remained mostly intact, and he just wanted to be done with it all.

Public Interest Projects

“One of Julian’s favorite questions was, ‘If you could do anything you wanted, what would you do?’” says Karen Ramshaw, vice president of Public Interest Projects. In 1991, she relates, his attorney, Pat Whalen, “started telling Julian how great it would be to work with community businesses and really help them become sustainable.”

At first, says Whalen, Julian “wanted me to have all the money. We were going to do a private, nonprofit foundation: I’d be running it, and he wouldn’t have anything to do with the money.”

But after extensive research and many back-and-forths, Whalen convinced Julian that the nonprofit model could be a hindrance. “I told him we could just make it a for-profit business, and if we lose the money, we lose the money, but we’re free to operate however we want,” Whalen explains. “We were trying to recycle it to generate money for the next business.” On that basis, Public Interest Projects was established in 1991. There was also a nonprofit, Public Interest North Carolina, to support things like advocacy and investigative journalism that couldn’t be funded through the Community Foundation.

Initially, PIP targeted all of Western North Carolina. But Whalen soon realized that even Julian’s wealth wasn’t sufficient to impact that big an area, and the company narrowed its focus to downtown Asheville. “The goal,” he says, “was to make Asheville this great urban, livable place.”

Whalen, though, is quick to credit both city officials and pioneers like Tops for Shoes, Roger McGuire and John Cram, who helped lay the groundwork for downtown revitalization. “Without the wisdom and courage local government showed in the ’80s, this would not have worked out,” stresses Whalen.

Nonetheless, in the early ’90s, there were few people living downtown, apart from the poor and the elderly. A couple of buildings had been renovated, with the upper floors turned into pricey condos. “There was no evening activity other than problems,” Whalen recalls. But a fire in the Carolina Apartments on North French Broad Avenue created an opportunity, and they seized it eagerly.

Advisers, remembers Ramshaw, said, “Nobody’s going to rent this. There’s no parking: It’s just stuck here on the side of downtown.” Nonetheless, PIP bought the property, whose 27 units were fully rented before architect and developer Jim Samsel had even finished renovating them. “The early tenants were walking on plywood boards through a sea of mud, because we hadn’t finished landscaping the courtyard,” she says.

The former Asheville Hotel — in whose shadow Julian had wept in the street back in 1989 — was the next ambitious undertaking. Besides converting the upper floors into affordable apartments, PIP persuaded Malaprop’s to move into the ground floor, offering the iconic bookstore a fluctuating rent to help it afford the larger space (see “A Roost for Readers”).

PIP subsequently converted the adjacent J.C. Penney building into condos and commercial space. “We had two to three people signed up for every unit before we could finish the project,” says Whalen.

Beyond housing

It wasn’t just about housing, however: Price and PIP aimed to create a total urban experience. Been to a show at The Orange Peel lately? Enjoyed a vegetarian meal at the Laughing Seed? Ordered tapas at Zambra? Taken a stroll through the Grove Arcade? Sat on a bench in Pritchard Park? Walked the Urban Trail, downtown’s self-guided walking tour? To varying degrees, these and many more projects and entities benefited from Price’s generosity and PIP’s mission (see sidebar, “An Extraordinary Legacy”).

“At one point, The New York Times wrote an article on Asheville restaurants,” says Whalen. “Five were mentioned; we were involved with four of them.”

And while few knew this, that was precisely the point. The money came with no strings attached, because Julian didn’t want downtown Asheville to turn into one man’s vision: He simply wanted to help.

“We were blessed with a lot of entrepreneurs who wanted to do it,” says Whalen. “We just had to be patient with them and be willing to put in more money … and help them make the decisions they needed to make to be successful. And frankly, that’s one of the miracles of our experience in Asheville.”

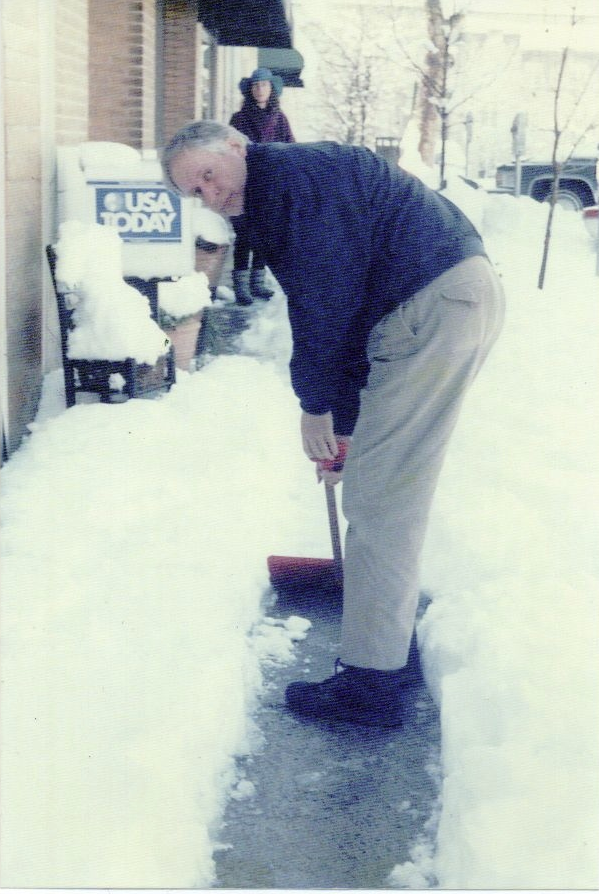

Julian wasn’t just a philanthropist, though: He lived and breathed downtown, doing whatever he could to make it better. “There seems to be this concept that individuals can’t make a difference,” notes Ramshaw. “But a lot of the things Julian did, you didn’t have to have money to do.” That included things like picking up trash, planting flowers in Pritchard Park, looking after the street trees, fixing the loose armrests on public benches and writing articles for Mountain Xpress and other local publications.

Money, of course, played a major role in what Julian accomplished, but it was the combination of his willingness to lose money or simply give it away and his profound personal commitment that made his enormous contribution unique.

In addition to businesses, Julian worked with numerous environmental groups. He lent RiverLink $64,000 to buy Warehouse Studios, giving the nonprofit a home in the River Arts District that also included studio space for artists. In addition, he funded projects for the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project, the WNC Alliance (now MountainTrue), the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, Asheville GreenWorks, MAGIC community gardens and many others.

The vision of a livable downtown also fit with Julian’s long-standing environmental concerns. Instead of converting another farm or hundred acres of forest into a subdivision, PIP “wanted to give people the opportunity to live downtown and walk to work,” Whalen explains.

Twenty-five years later, this aspect of the vision is still a work in progress. “The way we’ll know we really did things right as a downtown is the day a school bus makes a stop here,” says Ramshaw. “We don’t have the mix of housing that we hoped to have. I think there’s still a lot of opportunities, but the only way this is going to happen is if we start working more creatively and collaboratively. That seems to be something we’re not doing very well as a community right now.”

The Julian Price Project

Price’s end came suddenly: Diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in September of 2001, he died on Nov. 19. And in the years since then, his fierce desire for privacy has obscured his enormous contribution to this city. To address this, Rachel Price and Meg MacLeod have launched The Julian Price Project.

“I’ve been in the trenches of Asheville history — especially downtown history — and I’d never heard his name before,” says filmmaker and oral historian Erin Derham, whose documentary “Julian Price: Envisioning Community, Investing in People” will debut at The Orange Peel on Thursday, May 26 (see accompanying story, “Man About Town”). “That was the main reason I took the project on. It was wrong that I didn’t know about him. … There are so many people who get lost in history who did so much. He couldn’t be one of those people.”

The Orange Peel event will officially launch The Julian Price Project (see “The Sound of This Town” elsewhere in this issue). In addition to the film screening, the celebration will feature performances by Free Planet Radio, Doc Aquatic and Matt Townsend, plus “an insane amount of food,” says Derham. “Julian did so much for the community, so everybody he helped wants to be a part of it.”

A website is also in the works, and the project hired local writer Dorothy Foltz-Gray to produce a series of articles highlighting different aspects of Julian’s accomplishments and contributions. “They really wanted me to give the sense of Julian as a man, as a person, and tell his story in a warm and sometimes funny way,” she explains. Those articles will be posted on the website; some may also appear in various local publications, including Mountain Xpress. Excerpts from one of them, presented as stand-alones, accompany this story.

Both Whalen and Ramshaw jokingly note that Julian would never have approved of the project. “He would have moved out of town,” Ramshaw says with a laugh.

Whalen agrees, saying, “We can only safely do this because Julian isn’t here. But he’s not here, and his story is one people should know.”

In a sense, says Foltz-Gray, “Julian Price didn’t die, and we don’t have to let him die, because he showed us how to do it. How to invest ourselves in every piece of paper that somebody drops on the street or every cigarette butt that people flick. He gave us that power.”

To get a better handle on her subject before the filming began, Derham spent days holed up in UNC Asheville’s Ramsey Library. MacLeod had donated some of Julian’s papers and other materials to the library in 2004. Alongside his radio broadcasts and writings, Derham found an entire box of thank-you letters Price had saved, which she found deeply moving.

“It meant a great deal when people appreciated him,” says MacLeod. “When somebody sent him [a letter], he’d show it to me and just sit there and read it. … The thing that was hard for him was when it was done in public.”

My husband and I moved here in 1982. We have watched Asheville grow from a mostly boarded up city into the wonderful city it is today. Thank you for this wonderful article about Julian Price . Without his vision and resources and the vision of people like him Asheville may never have become the Paris of the South it is today. We need more people of wealth like him in the world who put what in the end benefits everyone ahead of greed.

Thanks for the comment Sharon. I hope you’re able to make it to the Thursday night event at the Orange Peel.