Tucked away on dusty courthouse shelves across the South, long-forgotten documents record the names of countless African-Americans whose forced labor was a cornerstone of the region’s economy.

Western North Carolina lacked the requisite climate and flatland for large-scale rice, tobacco or cotton production. Nonetheless, in Buncombe County, thousands of slaves toiled as cooks, farmers, tour guides, maids, blacksmiths, tailors, miners, farmers, road builders and more, local records show. And after mostly ignoring that troubled history for a century and a half, the county is now taking groundbreaking steps to honor the contributions of those former residents by making its slave records readily available online.

Thanks to a partnership between the register of deeds office and UNCA, Buncombe has apparently become the first county in the country to digitize its original slave records, local officials and researchers say. And though the records paint only an incomplete picture, the agency “is showing that another group of people existed — and contributed to the building of this state, this county, this city,” UNCA assistant professor Darin Waters explains in a recent county-produced documentary about the project (see sidebar, “Forever Free?”).

“It was the government that allowed slavery to exist from the very beginning,” he notes. “And so I think it’s important for government agencies to be in the forefront of acknowledging the past, which was essentially a crime against humanity.”

Unmarked trail

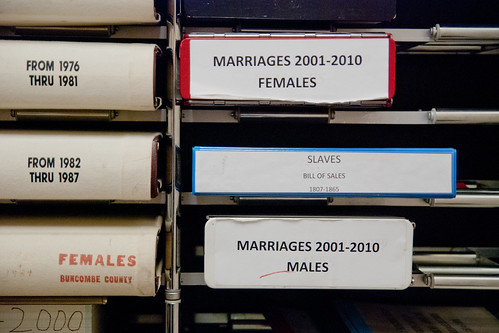

Until the 13th Amendment was ratified in 1865, slaves were considered property, and transactions involving them were recorded at the local register of deeds office, alongside the ones concerning farm animals, wagons and tracts of land. Those sale books basically languished in storage, pushed aside like the memories of slavery itself. But in Buncombe County, that began to change 13 years ago, when local real estate attorney Marc Rudow alerted his wife, Deborah Miles, that he’d come across such slave deeds while researching a parcel’s history.

As director of the Center for Diversity Education, Miles spied a learning opportunity. She wrote a grant to hire about 20 high school students to sift the thousands of pages of documents, seeking clues about the lives of local slaves. “Sometimes it would describe the sale of a horse, or a load of corn, and other times it would all of a sudden say words like ‘girl’ or ‘14 years of age’ or ‘negro,’ or a name — Sally or Harriet — would pop out, and you realized they were talking about a person,” she recalls. Some of the results of that research were incorporated into An Umarked Trail, a guide to local African-American history that’s been used in the public schools.

For the most part, however, those records remained obscure until Drew Reisinger was named register of deeds in 2011. When Miles told him about the slave records, says Reisinger, he “couldn’t believe it.” He then began making some history of his own, becoming the first register of deeds in the South to put those documents online in readily accessible form.

“I think it’s our duty as record keepers, as registers of deeds and clerks of court, to make this information more available to the public,” Reisinger maintains. “I hope we can bring more attention to this subject: We want to make it easier for people to find their own family history.”

He recently sent a letter about the project to the North Carolina Association of Registers of Deeds; colleagues across the state (many of whom didn’t even know they had such information) praised the project, and at least one sought advice on putting their own records online, Reisinger reports.

“The idea of opening up public records starts in the earliest days,” he points out. “Let’s not pretend that slavery wasn’t a big part of Buncombe’s and the South’s economy.”

Getting the ball rolling

Local historians are starting to take notice.

Sasha Mitchell, who owns a business called Memory Cottage, works with individuals and groups to craft histories and exhibits. Current projects include documenting the African-American history of the Shiloh community in south Asheville and the YMI Cultural Center downtown. Mitchell also recently offered to research some family histories free of charge.

“I’m so happy that they have these deeds out there, and I hope more municipalities will do it,” she says. “The fact that it’s accessible is huge. … To have it where I can sit in pajamas in the middle of the night and look it up and have things at my fingers in a minute, that’s remarkable.”

There are still some big kinks in the system, however. One major flaw, says Mitchell, is that the database is searchable only by the names of owners rather than the slaves themselves (who often took their owners’ names, but not always). Also, the archaic handwriting can be hard to read in the digital scans.

Reisinger, meanwhile, says his office is still unearthing slave data in deeds of trust, mortgages, wills and other documents that aren’t yet part of the system. The existing database “was to get the ball rolling,” he notes; improving it will require time and assistance.

“I definitely think there’s a lot more left in these records that we could use the public’s help to find. While we don’t have funding to allow staff to be dedicated to searching old records all the time looking for them, if genealogists go through our records and do their own search, we’re always open to collecting more information.”

Mitchell says she’d like to help with that, and Miles is on the hunt for grants to hire more high school students.

Waters, an Asheville native, didn’t know about the Buncombe County records when writing his recently completed doctoral thesis on local African-American history. He wants to incorporate some of that information into an updated version of the manuscript for possible publication as a book.

To remember and to warn

Despite those efforts, the lives of most local slaves are unknown, their remains interred in unmarked graves scattered across the county.

In contrast, an 1860 census of their owners released by the register of deeds office reads like a who’s who of local notables. Prominent on the list are names like Woodfin, Patton, McDowell, Baird, Weaver, Vance, Merrimon and Reynolds, all familiar from the area’s streets, parks, buildings and monuments.

“The irony,” says Reisinger, is that his office on Woodfin Street is “named after Nicholas Woodfin, who was one of the largest slave owners in Western North Carolina.”

In 1860, Woodfin owned 122 of Buncombe County’s 1,913 slaves, census figures show.

Waters, while acknowledging those owners’ contributions, says he’d like to see more credit given to the African-Americans and other minorities who “did the hard work,” helping make the area what it is today.

“There needs to be an embrace of all of our history,” including the parts that are “painful to even think about,” Waters maintains. “I think it would be good if the city and county somehow began to acknowledge those other people, through memorials or the naming of streets.”

Miles, too, hopes the deeds project leads to greater recognition. Earlier this year, she wrote a commentary in the Asheville Citizen-Times calling for a marker to be placed on the Vance Monument downtown noting that slave sales, imprisonments and punishments were formerly conducted on the site.

“The word ‘monument,’” said Miles, “comes from the Latin ‘monere,’ which means to remind, to warn. I call on the citizens of Buncombe County, the governments … and the organized historical associations, along with all like entities across the South, to take the meaning of that word to heart.”

Recently, the Center for Diversity Education and UNCA’s Ramsey Library staged an exhibit honoring Abraham Lincoln, noted Miles, and “Many visitors, both black and white, had no idea slavery existed in the mountains.”

“This ignorance is dangerous,” she wrote in the Citizen-Times piece, because it “negates the contributions that African-Americans made to our region during this period of duress.”

Slaves, Miles maintained, created “the basis of the current tourism industry. The roads of central Asheville were built with slave labor (and then named for the slave owner to whose home the road led). And the beds of the existing railroad, which today deliver all the coal used to make the electricity in our homes, were laid by slave labor.”

Taking responsibility

Ultimately, the Buncombe County database’s usefulness as a research tool may depend on how many other agencies follow suit, since slaves were often sold across state and county lines.

“Once you have everybody’s information online, then you have a much clearer database,” Miles explains. “I think there’s enormous historical value in these records; we have only the slightest idea what that value is.”

But in the meantime, local historians say, the project also has great symbolic significance. “Instead of just sweeping slavery under the rug,” says Mitchell, “it’s the idea that it is still worth talking about by government entities.”

Waters concurs. “It says to those who are descendants of slaves that we are finally recognizing the humanity of your ancestors and the important role they played in helping create the society we now live in.”

That’s the ultimate goal, Reisinger agrees. “So often, when people talk about slavery in WNC, they’ll say it wasn’t that bad,” he points out. “And it’s almost like we’re not taking responsibility for what we did.”

During a recent run in West Asheville, Reisinger says he came across an old graveyard. Prominent headstones recorded the rank and lauded the valor of Confederate soldiers. Toward the rear, however, he spotted some little stones with no names on them.

That, he says, is where slaves were buried. “You realize that no one’s going to remember these people,” he reflects. “And I think the most important thing we can do is to continue to remember that they existed and try to tell their story.”

Buried memories: Unlike some of their prominent owners whose names are enshrined in local streets, monuments and buildings, the lives of most local slaves are unknown, their remains interred in nameless graves like this one.

Painful deeds: Until the 13th Amendment was ratified in 1865, slaves were considered property, and transactions involving them were recorded at the local register of deeds office, alongside the ones concerning farm animals, wagons and tracts of land.

Watch Buncombe County’s short documentary, Forever Free:

Might this effort be extended to coastal areas?

I have an ancestor who shows up as a free person of color in the early 1800s in the Albemarle Sound Area

The population of Buncomb County in 1860 is listed online as being 238,318 persons. And yet, as stated in this article, less than 2000 slaves were living at that time in the county. That is not even 10% of the population . Are we to suppose that this area was built by 2000 slaves and ignore the fact that the other 236,000 people had nothing to do with the hard work done at that time. My grandparents and great grands were born and raised in this area , in fact, my ancestry goes back to the 1700’s in W. North Carolina. They were very hard workers…clearing land with mules and hand labor…working in gold mines…farming. All labor at that time was hard, and few were educated enough to have jobs such as lawyers, doctors, teachers. I resent that Swedish and Irish, are ignored for their hard work to build society. Pointing a finger to say that black slaves did the hard work…that totally not true.

I think you might have misread that. The 1860 Census data I see says that there were 12,654 people in Buncombe County NC. The slave population at that time would have been not too different from the current African-American population, proportionally.