More than just birds are soaring the winds above Mount Mitchell.

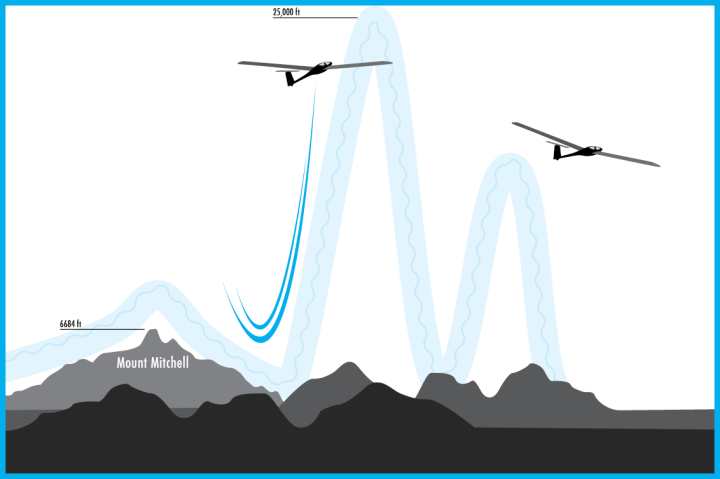

Dozens of pilots from around the country will soon attempt to fly motorless gliders over 20,000 feet above the area’s highest peak. They hope to be propelled upward by a natural phenomenon known as wind waves, which crest when air currents blow against the mountain ridge from the northwest. The Black Mountain Range is one of the only places in the eastern U.S. where such massive updrafts occur, sometimes lifting gliders at speeds of more than 1,000 feet per minute.

The flights are fraught with dangers, as the waves also come crashing downward, creating extreme turbulence that has the potential to thrust the crafts toward the ground at similarly fast rates. Even if everything goes well, participants must take a range of steps to deal with the thin air, frigid temperatures and other challenges.

“If you get in the wrong place — the sink — the air can be coming down fast, like a rock,” says John Good, an experienced pilot who volunteers for the Soaring Society of America. “So you have to be smart and knowledgeable enough to sort that out. And careful enough so that if you get it wrong, you still have a safe place you can land.”

Another adventurous pilot, Sarah Arnold, who’s organizing this year’s annual Wave Camp, says the “uncertainty of the weather” is just part of the thrill of flying. For her, the inherent risks are well worth the rewards.

“I love the beauty of it,” she says. “You’re up there flying under all those cumulus clouds, and you look up and see the sun coming through, against the sky. To me it’s the ultimate meeting of art and science. They come together in soaring in just the most incredible way.”

Land of the sky

Most of the year, the skies over Mount Mitchell are reserved for commercial jetliners as they zip between major nearby hubs such as Charlotte and Atlanta. But the Federal Aviation Administration has granted gliders permission to sail the area’s winds for a week or two each year since the mid-1970s, redirecting jetliners to avoid crashes.

The ’70s were the sport’s heyday, and in 1978, John Cross broke the state record for motorless flight above Mitchell, rising to a height of 29,350 feet.

Arnold, who has been organizing the local gatherings since 2011, also operates a gliderport in Chilhowee, Tenn., which offers rides and instruction. In recent years, the sport of soaring has been seeing a resurgence, she says, noting that people are coming from as far away as Colorado this year to ride the Mitchell wave.

Her main duty will be towing the gliders from the Shiflet airfield in Marion up in a traditional gas-powered plane to about 7,000 feet toward the mountain ridge, looking for the most powerful wave to release them into.

It’s a tough job, even with the luxury of motor power. “In between those waves, there’s extreme turbulence,” she says. “That’s very challenging.”

Arnold and other participants will be hoping for better luck than they had at last year’s camp, which was marked by poor weather and an unfortunate crash. Jay Campbell slammed his glider into a tree along Big Ridge Road near Mitchell. He suffered severe injuries but survived after a rescue crew lowered him, according to WLOS reports.

It was the worst accident since Arnold’s been organizing the camps. “I wouldn’t do it every year if I thought there was a high chance of someone getting hurt,” she says. “I wouldn’t feel like that would be responsible, but it is a higher-risk activity than your average soaring.”

Good says he actually has happy memories from last year, when, after reaching an elevation of 18,000 feet near Mitchell, he soared south over Asheville before swinging back to the Marion airfield. He’s been preparing for this year’s camp from his home in Pennsylvania, scouring images of Western North Carolina on Google Earth, which provides detailed views of the area’s topography.

The key to safety, he says, is making sure there’s “a safe, landable place in reach all the time.”

However, that place might not always be an airstrip. “Sometimes we end up in a farm field, not infrequently, but the gliders can handle that quite nicely,” he says. “We don’t think of that as an emergency. You learn the skill of judging fields from the air: What’s the slope of the field? What’s the surface look like? Are there wires in the way? That’s more or less a normal thing.”

If he finds himself over Asheville without enough wind beneath his wings to make it back to Marion, he notes: “The Biltmore House has some beautiful fields. They might not be happy. You might have to do some explaining, but you’re not going to do damage. That’s a place where you could land. … It’s always good to study an area and see where the fields are. It’s sparse fields between Asheville and Marion.”

The responses he’s received from farmers after landing in their fields has run the gamut over the years. While some have been annoyed, others have taken him up on offers to hop aboard the glider with him. “Almost always you can handle it just by being nice,” Good says. “You have to use diplomatic skills.”

As safe as you make it

For those wanting to give gliding a try, Good will offer instructional flights for beginners and experienced soarers in Marion this year in his two-person glider. “The people in the general public — not that many of them know about this phenomenon. Many are very surprised when you tell them you’re going to fly a motorless airplane to 30,000 feet,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Jay Campbell

While he readily admits that “the overall accident record in small planes and gliders is significant,” Good says most of the problems people run into can be avoided with proper training and preparation. “When people get in trouble, it’s overwhelmingly because they did one of the things wrong that is known to be a thing that you must not do,” he explains. “In other words, people are getting in trouble by making known errors and mistakes. It’s as safe as you make it.”

For clients, he wants to make it as safe as possible, steering clear of the wave’s highest reaches and avoiding long distances.

“The safety record of flying guests in gliders is really quite good,” Good says. “It’s quite interesting and instructive for people who haven’t done it. You have to figure out what the science and the clouds are telling you. It can be rather complicated, but it’s always interesting.”

The 2015 Wave Camp is based at Shiflet Field in Marion and runs through Feb. 24-March 5. For more information email John Good at john.f.good@gmail.com. or visit the Wave Camp website.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.