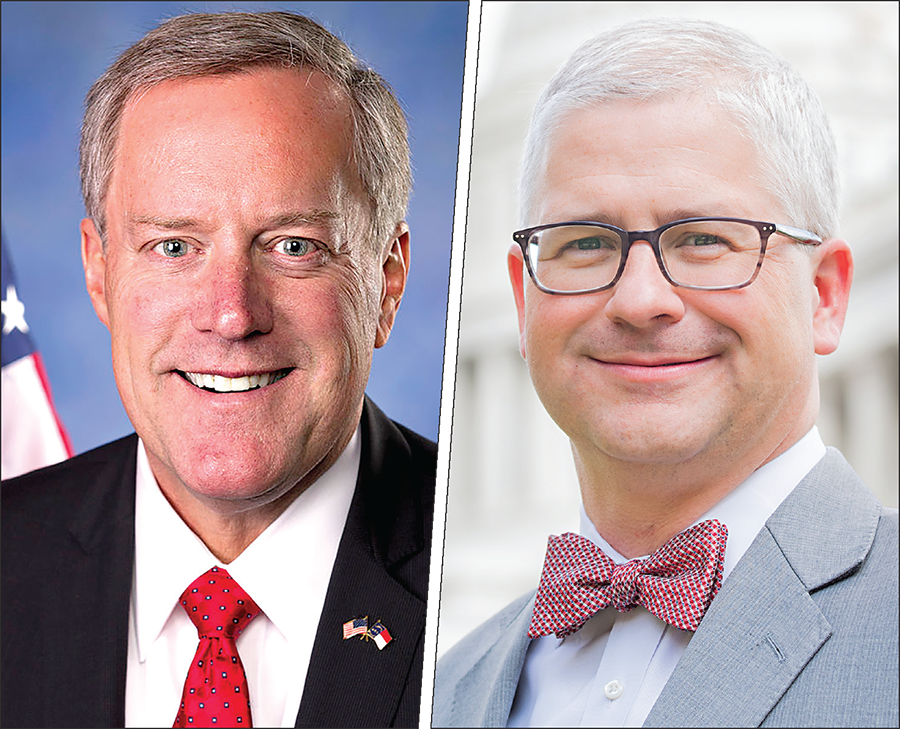

The two Republicans who represent almost all of Western North Carolina in the U.S. House probably didn’t need huge campaign war chests to win their 2018 general election campaigns, but money from donors across the country rolled in anyway.

In the 10th Congressional District, which stretches east from Asheville almost to the western edge of Charlotte, the almost $3.8 million that Rep. Patrick McHenry raised for his campaign was 29 times the total collected by his opponent, Democrat David Wilson Brown.

In the 11th District, which encompasses most of WNC that’s not in the 10th, the $1.9 million that supporters gave Rep. Mark Meadows was eight times what Democrat Phillip Price raised.

These figures were generated from reports sent to the Federal Election Commission. Federal law requires political campaigns to submit periodic reports to the FEC detailing the moneys raised and spent.

Much of McHenry’s haul came from people working in the finance, insurance and real estate sector and the political action committees that represent businesses in those fields, his reports show. McHenry is the ranking minority member of the House Financial Services Committee.

Meadows apparently benefited from his increasingly national exposure as a leader of the most conservative group of House Republicans. He is chairman of the Freedom Caucus and gained notice through his efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act and push then-Republican Speaker John Boehner out of office as well as clashes with Boehner’s successor, Paul Ryan.

Both WNC congressmen represent districts that are staunchly Republican. But most of the money they used to run their campaigns and boost GOP candidates in more competitive races came from outside of North Carolina.

Donors back presumptive winners

Both Meadows and McHenry won their respective 2018 races with 59% of the vote. According to their campaign finance reports and what their opponents suggest, those campaigns were fairly low-key, with little advertising.

So why did people give them so much money, and how much difference did it make in the outcome of those races?

Or as Chris Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University, puts it, “Are they winning because they’re raising money, or are they raising money because they’re winning?”

Cooper favors the latter explanation. Donors, he believes, felt confident that McHenry and Meadows would be reelected and wanted to be in their good graces.

“Contributors invest their money strategically, like they do in the stock market,” says Cooper, favoring candidates who have a good chance of winning and influencing policy debates in Washington in ways the donors agree with. Academic studies, he says, suggest that those who give to campaigns aren’t buying votes, because the candidates they support already agree with them.

Instead, continues Cooper, contributors are trying to make it easier to get their foot in the door once the candidate is elected — in addition, of course, to boosting their favored politician’s chances in the relatively small number of races that are genuinely competitive.

Giving money “buys participation,” he says, increasing the odds that a politician will pay attention to the donor’s concerns. There are thousands of issues that Congress might consider, and by making a campaign contribution, “You’re moving your issue up the list.”

The “gilded panel”

Recalling his childhood, McHenry likes to tell the story of his father’s difficulties finding funding to start what became a successful lawn mowing business. The congressman credits that experience with driving his desire to make it easy for worthy borrowers to get credit — and his opposition to government regulations that he maintains make lending unnecessarily difficult.

That stance is music to the ears of many in finance, insurance and real estate. The sector accounted for $1.7 million in direct donations to McHenry’s 2018 campaign, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan group that monitors campaign spending. People and political action committees in those industries also accounted for $1.4 million in donations to two related PACs authorized by McHenry that supported Republican candidates. One of those groups transferred more than $976,000 to McHenry’s campaign.

Those amounts worry Brown, McHenry’s erstwhile opponent.

“If you’re getting that much from the people you’re supposed to be [performing] oversight on and regulating, I can’t imagine that you can … be favorable for the consumer as opposed to your corporate sponsors,” he says. “I think he should have to wear [donors’] logos like a NASCAR guy.”

Asked about Brown’s comment, Jeff Butler, a spokesperson for McHenry’s campaign, said the congressman’s “top priority is serving as the 10th District’s voice in Washington while also advancing a conservative policy agenda that reflects our area’s shared values.”

Earlier this year, The Washington Post called the House Financial Services Committee the “gilded panel,” because large amounts of campaign cash typically flow to its members, regardless of whether they’re Democrats or Republicans. During the 2017-18 session, McHenry was the committee’s vice chair, and when its chairman retired and control of the House shifted to Democrats, McHenry became the ranking minority member.

He was also chief deputy majority whip during those years. That made him part of the House leadership, whose members typically help raise money for their party’s other candidates — a responsibility McHenry has clearly taken seriously.

His campaign reported expenditures at upscale hotels in Boston, Los Angeles and more than a dozen cities in between, plus numerous payments to fundraising consultants and caterers. The campaign reported spending at least $53,785 with American Airlines alone, although the FEC reports don’t distinguish between fundraising trips and those made for other campaign-related purposes.

McHenry’s campaign reported almost $1.9 million in donations to two groups that seek to elect Republicans to the House, plus some smaller contributions to individual GOP candidates or groups. In addition, his two affiliated PACs gave more than $1.1 million to support Republicans, according to Center for Responsive Politics data.

Data from FollowTheMoney.org, which tracks campaign financing, shows that both McHenry and Meadows got less than half their contributions from inside North Carolina; a much higher percentage of the money raised by Brown and Price appears to have come from within their home state.

There’s also a disparity in the size of the donations to the candidates. Gifts of less than $200 accounted for more than 40% of the total receipts for both Democrats. Meadows’ campaign, meanwhile, pulled in $567,694 in small gifts, but they represented a smaller portion of his total donations.

Meadows frequently appears on television news shows and is often quoted by print and electronic media. Cooper says the congressman’s campaign finance figures suggest that he draws contributions from right-wing donors across the country.

“He’s a national figure. Every time you’re on the Sunday morning talk shows, a conservative voter in Wyoming knows who you are,” notes Cooper.

A Meadows spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

Brick wall

Still, Cooper, Brown and Price all say it’s simplistic to attribute McHenry’s and Meadows’ 2018 victories solely to the fact that they outspent their opponents. Those districts’ overall Republican tilt also had a lot to do with the outcomes, stresses Cooper, and Price agrees, at least when it comes to the 11th.

When the Republican-controlled N.C. General Assembly redrew the boundaries in 2011, it removed most of Asheville from the district, making it much friendlier to that party’s candidates. The following year, Price points out, incumbent Rep. Heath Shuler, a Democrat, didn’t even seek reelection.

The 2011 redistricting is being challenged in court as a partisan gerrymander designed to favor Republicans. Two separate legal actions have been consolidated into a single case that’s now before the U.S. Supreme Court; a ruling is expected by the end of June. Regardless of the outcome, however, new lines will have to be drawn after the 2020 census. Price says he’ll very likely make another bid for the House seat, stressing that “I’m not going to do it with the current [district] map: It would be like running into a brick wall.”

Brown, meanwhile, has already announced that he’ll run again next year. He says he’ll focus more on fundraising this time, adding that McHenry’s strong connections to banks and other financial services firms make it unlikely that he’ll be able match his opponent’s spending.

“If I caught fire and started getting a bundle [of contributions] and outside groups started getting interested, he’d put more money into the race,” Brown predicts.

Being outspent by an opponent doesn’t automatically doom a candidacy, however. In 2018, there were several races around the country in which candidates with less money won anyway. Nonetheless, says Cooper, it’s very hard to win a U.S. House race unless the candidate can raise at least $1 million.

Referring to the fundraising disparities in the 10th and 11th District races, he says, “I think those kinds of numbers are nearly impossible to overcome.”

And barring a court-ordered redrawing of the district lines in advance of the 2020 election, whoever McHenry and Meadows end up facing will most likely be at a financial disadvantage.

McHenry’s campaign ended 2018 with $1.3 million in the bank, and Meadows had nearly $700,000. During the first quarter of this year, each raised more than $200,000.

Even apart from what those dollars can buy, says Cooper, members of Congress keep raising money partly because having a hefty bank balance is “a threat to anybody who might run against you” and thus can deter prospective opponents. “It’s kind of the gun behind the door.”

Mark, either you know this and chose not to include it in your piece or somehow this is news to you, but there is absolutely nothing unique about the WNC situation. You’ll find similar stats in virtually all congressional races.

Did you know and it just didn’t fit into your theme?

Did the piece assert that it was a unique situation? Yes, incumbents typically have a fundraising advantage, but one impact of the gerrymandering west of I-77 is to disengage voters of both parties from those races. Barrett asks a simple question: given that both NC-10 and NC-11 are uncompetitive, why are the incumbents still showered with campaign cash, and where does it come from? With McHenry, it’s simple enough: he’s gained sufficient seniority to have his wheels greased. With Meadows, who has no real seniority after 6+ years but shows up on TV every day and apparently has a direct line to the White House, it’s more like Patreon for being a blowhard zealot.

indy499, the story doesn’t claim that fundraising patterns in the 10th and 11th Congressional Districts are unique. However, I think your statement that, “You’ll find similar stats in virtually all congressional races” is overly broad at best. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the average incumbent raised nearly $2 million on his or her U.S. House campaign in 2018 and the average challenger got $1.1 million. (The CRP figures are only for candidates in the general election. Likewise, my story doesn’t look at the candidates who lost in the primaries.) Challengers in the 10th and 11th raised only a fifth of that amount, or less, and the amount Rep. McHenry raised was close to double the average incumbent’s haul.

To the extent that there is any “theme” to my story, it is how much did the candidates in the 10th and 11th raise and spend and where did they get their money. Certainly the national situation is relevant, but it was not my main focus.

DEMOCRAT GINA COLLIAS is challenging McHenry in 2020. She is uniquely positioned to win the roughly 14% of the moderate Republican vote she got in the 2018 primary, and to build a coalition of Unaffiliated voters and Democrats. Gina realized that the Democratic Party represents the values and goals that match her own. District 10 & WNC needs to win this seat! Gina is an attorney with passion, empathy, and an undaunted drive to make NC-10 and our country a better place! Read more at her website below. This article should be a WAKE UP CALL to all who are dissatisfied with the hijacking of our country and the lack of moral courage in the Republican Party. Get involved. Join us! Gina has a strong, experienced team in place, but she needs your help! Volunteer, Donate what you can at the ActBLUE link below (perhaps in a monthly donation), and help get out the Vote!! Her VALUES inform her positions, which have not changed. (Click VALUES on her website). If you want to hear what made her part of the RESISTANCE from day #1, watch her speech from the NC-10 Dem Convention & other speeches (click MEDIA). Thank you for supporting the Gina Collias for Congress Campaign! Democrat for U.S.House in District NC-10. Join us! Let’s turn NC Blue!! DONATE HERE via ActBLUE —>

http://bit.ly/2MCPMaq Please share! http://www.GinaColliasforCongress.com

This sentiment is great, and Gina seems nice, but let’s be honest, McHenry isn’t going to lose. There are races within the 10th district that are worth a challenge — city councils, county commissions, school boards, etc. I’ve no idea what’s happening in Shelby or Gastonia or Rutherfordton, but if you live out there, run for something and make your case.

The Mountain Xpress article refers to the Democratic challengers (Price & Wilson) as “outgunned”. And to be sure, by every measure, they were. So maybe we need new “guns”. Steve Woodsmall (Dist. 11) & Gina Collias (Dist.10). http://bit.ly/2MCPMaq