On Sept. 27, 1979, the Asheville Housing Authority received a brief letter from Mrs. E.W. White of Atlanta. She wrote:

“My parents, Mr. and Mrs. Willie E. White of 218 South Beaumont Street, Asheville, N.C., have lived at this address almost fifty years. Although they are both in their seventies, they were none-the-less uprooted from their home and required to move by the Asheville Housing Authority. I can’t begin to tell you what this does to individuals who have built memories and accumulations around their residence for almost fifty years.

“I am the only daughter and it is my feeling that since they were forced to move, it was in their best interest to move near me. Since my parents are both on a small fixed income, they are unable to afford the move and it is our request that the Housing Authority pay all moving expenses.”

Nearly 30 years later, White’s letter was one of thousands of documents concerning the city’s urban renewal projects that were transferred from the Housing Authority to UNCA’s Special Collections in 2007. As in hundreds of other cities across the country, urban renewal dramatically changed Asheville’s neighborhoods. Established by the Housing Act of 1949, the federal initiative aimed to clear blighted areas. In the process, however, it displaced millions of predominantly African American individuals and families between the 1950s and the 1980s, according to Mindy Thompson Fullilove’s 2004 book Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It.

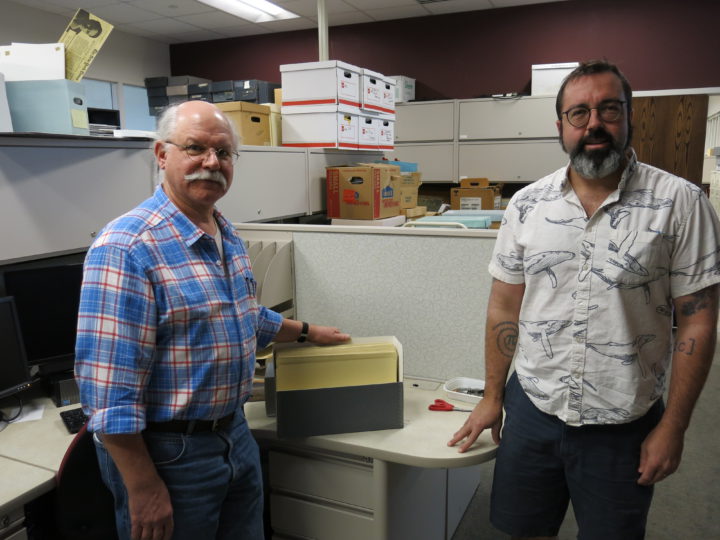

Gene Hyde, the university’s head of special collections, says the documents pertain to some 2,000 commercial and residential properties. Laid end to end, he notes, the boxes would extend 167 feet. Over time, Hyde and fellow archivists have worked on organizing the material to make it more accessible to students, community members and other researchers.

In recent months, UNCA students scrutinized a few of the files as part of a project exploring urban renewal’s local impact. Time constraints limited the scope to six properties, including 218 S. Beaumont St. Yet by narrowing their focus, says Patrick Bahls, his students provided a unique history of individual cases that might otherwise be overlooked or lumped into national statistics.

Bahls, who directs UNCA’s honors program, says that when he was in high school in the late ’80s and early ’90s, “Not a word was said” about urban renewal. Even today, “Depending on the school district and the honesty with which various communities are willing to confront their histories, there is still a good number of students for whom this is totally new.”

Seeing red

The 1950s marked the launch of urban renewal projects, but their roots reach back decades earlier through a pair of influential federal programs. “Redlining certainly sowed the seed,” says Bahls.

In 1933, the Home Owners Loan Corp. was formed as part of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Great Depression had triggered a housing shortage, and the agency was tasked with preventing further foreclosures by refinancing home mortgages. Instead of loans that required a large down payment and had to be paid off within five-10 years, qualified homeowners could now obtain a much longer-term, lower-interest mortgage with a mere 10% down.

To determine eligibility, the agency created color-coded maps of metropolitan areas throughout the country. Green areas, rated “A” and considered “best,” qualified for refinancing; red areas, rated “D” and deemed “hazardous,” were denied that opportunity.

In 2016, the University of Richmond and three other schools created “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America.” The online, interactive map enables users to examine the federal agency’s conclusions concerning cities across America, including Asheville. (To view the map, visit http://avl.mx/6xl).

Asheville’s map, completed in 1937, designated a large part of the city in red. Field notes from the effort indicate that all of the “hazardous” areas — including the East End and South Side neighborhoods — were majority black. And in green areas like North and South Asheville, the agency specifically recorded the absence of “Negro” inhabitants.

Meanwhile, in 1934, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration. As historian Richard Rothstein explained in a 2017 NPR interview, the agency subsidized builders to mass-produce subdivisions “with the requirement that none of the homes be sold to African Americans.”

These discriminatory programs had profound consequences, noted Rothstein. “Today, African American incomes, on average, are about 60% of average white incomes, but African American wealth is about 5% of white wealth. Most middle-class families in this country gain their wealth from the equity they have in their homes.” Barred from buying suburban properties, he continued, black families “gained none of the equity appreciation that whites gained” during subsequent decades.

Bahls notes the “tight connection” between these New Deal policies and urban renewal. The neighborhoods deemed blighted in the 1960s were the same ones whose residents were denied loans in the 1930s. “Redlining played a role in perpetuating a cycle of disinvestment in African American neighborhoods,” Bahls maintains. The result was that thousands of Asheville residents lost their homes — and whole communities disappeared.

Paved over and covered up

A recently concluded exhibit at UNCA gave detailed histories of the six properties Bahls’ students researched. Four properties, including 218 S. Beaumont, are vacant lots today. A parking lot now occupies the site of the exhibit’s lone commercial building. The sixth property, acquired by the city in 1988 and intentionally destroyed during a Fire Department training session, is now part of Martin Luther King Jr. Park, which features a statue of the late civil rights leader.

Freshmen Anna Davis, Eva Rodriguez-Cue and Julia Weber, who focused on 218 S. Beaumont, say they knew very little about redlining before beginning their research. “I understood that institutionalized racism was a huge issue in the United States,” Davis explains, “but I didn’t understand how integrated it was.”

Nor had they considered the importance of community in individual lives. The East End neighborhood, wrote UNCA history professor Sarah Judson in a 2014 article in The North Carolina Historical Review, was “crucial for black survival and upward mobility. … The presence of local midwives and undertakers meant that neighborhood residents could patronize black-run businesses literally from the cradle to the grave.”

Contemporary newspaper articles underscored how residents facing displacement felt about their neighborhood. A March 1, 1978, Asheville Citizen story detailed East End residents’ recommendations to the city. Besides improving the storm drainage system, streets and sidewalks, the group asked that those required to move be relocated “within the neighborhood if at all possible.”

Yet by 1982, noted Judson, Valley Street, “the historic root of the neighborhood, was gone, redirected and renamed South Charlotte Street after Charlotte Patton, a member of the prominent Asheville slaveholding family. Pathways that interconnected lives and destinations were paved over to make municipal garages and administration buildings. People who had lived in the dense housing of the neighborhood found themselves in public housing communities or in far-flung neighborhoods, away from those important networks of support.”

Meanwhile, newspaper accounts painted a vastly different picture. “From one of the city’s worst slum areas, East End has become a vital neighborhood,” the Sunday edition of the Citizen-Times declared on June 23, 1985.

Rodriguez-Cue says she began her research “completely blind: I’d never heard about urban renewal.” Since completing the class, however, she’s begun researching the complex history of her hometown, Greenville, N.C.

“So often,” says Weber, “it seems these things are very covered up.”

Shifting the conversation

Other local educational efforts send a similar message.

Paulina Mendez, a training consultant with Asheville’s Office of Equity & Inclusion, leads monthly two-hour training sessions that are open to all city employees and elected officials. Advancing Racial Equity 101, she says, introduces key concepts while offering a detailed look at government’s role in creating and sustaining racial inequities.

“People have a tendency to think things like urban renewal … can’t happen here, because we’re so progressive,” says Mendez. “But … there are people in our community that have directly felt the effects of that and are still experiencing them.”

This spring, local storyteller Roy Harris will launch a monthly program at the new LEAF Global Arts center in The Block, the city’s historically African American business district. African American residents will share their memories of the Del Cardo Building (the center’s home) and the neighborhood.

“I don’t care what you talk about in Asheville, urban renewal will come up,” Harris maintains. Displaced family members, he says, have passed down stories of their triumphs and tribulations to subsequent generations.

Before stepping down as chair of the city’s African American Heritage Commission last October, notes Sasha Mitchell, she proposed a moratorium on all future development projects involving properties acquired through urban renewal until a comprehensive cost analysis is conducted. Such a program, she says, “could be a model for other cities, because this is a problem that has happened all over the country.”

“My hope is that once we have this study and others like it across our nation, our conversation could shift toward acknowledging that government policies targeting our nation’s black population resulted in losses of wealth and capital that have never been calculated,” Mitchell explains. “Once we understand the true nature and value of that loss, rather than repeatedly noting the awful disparities black residents of Asheville live with today — which, without context, many people attribute to failures of the black community — we can talk about how we can begin to right that wrong.”

At press time, Xpress had not heard back from Lynn Smith, the current chair of the African American Heritage Commission, concerning the proposal’s current status.

These recent initiatives are part of an ongoing local push to honor the city’s displaced communities. Those efforts include photographs by Andrea Clark and Isaiah Rice, the Triangle Park mural, DeWayne Barton’s Hood Huggers International tours and programs like Building Bridges. Meanwhile, the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library continues to expand its collection of materials documenting local African American history.

Still, Mitchell worries about black Asheville’s future. In 1950, African Americans accounted for 21.7% of the city’s population, census figures show; by 2010 that number had dropped to 13.3%. “We’ve lost a lot of talent; the black middle class is shrinking,” she laments, and the city’s rapid gentrification seems likely to accelerate that loss.

All things considered

Despite these injustices, the historical picture isn’t uniformly bleak, some commentators maintain.

“Today, the dispossession of neighborhoods continues to resonate with most of those who were displaced,” Judson wrote in “Twilight of a Neighborhood,” a 2010 article in Crossroads. But for some African Americans, she noted, “Urban renewal promised to rebuild cities and create positive changes in areas that looked as if they needed help.”

David Nash, the Housing Authority’s executive director, agrees. “There are two lines of argument that I’ve heard in the past that aren’t exactly true about urban renewal,” he says. One is that there was no regard for historic preservation. “But if you drive down South French Broad or the streets off South French Broad, you will see a lot of historic structures that were not torn down during urban renewal.”

The second claim is that the experience was universally negative. Nash cites a Housing Authority program begun in the 1970s that offered a tiny percentage of the displaced community members a chance to buy back plots of land from the city for $1 after the homes on them had been torn down. According to documents in UNCA’s special collections, 72 such lots were available in the East Riverside community, with six more in the East End/Valley Street neighborhood.

“It doesn’t diminish the fact that there was a huge amount of disruption in people’s lives,” stresses Nash. But at the same time, “I’ve heard people talk about the disruption but then also talk favorably about being able to move into public housing.”

Bahls says his honors class tries to include all aspects of urban renewal’s complex history, which is why he invited Nash to speak with his students. “What often gets lost in the discussion is that there were a lot of good intentions,” says Bahls, adding, “Of course, we all know where that road leads.”

To complement Nash’s presentation, the class read Root Shock as well as articles by Judson and Nina Flagler Hall.

For Weber, the class, “was a huge exercise in learning what it means to listen — and what it means to be comfortable with silence.” It also raised questions about equity, white privilege and the ongoing legacy of institutional racism — topics that she and her research partners say they’re still wrestling with.

The 21st-century problem

In the introduction to Root Shock, Thompson Fullilove states that urban renewal bulldozed 2,500 neighborhoods in 993 American cities. Together with the individual case studies in the book, those numbers helped shape the author’s deep conviction about this country’s future.

“One hundred years ago,” she writes, “the distinguished African American scholar Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that the problem the 20th century needed to solve was … the color line. It took 60 more years for the United States to engage wholeheartedly in the battle for civil rights. Yet as we have faced the truth of the color line, we have acted, reacted, thought and felt differently. We are a better nation for it.”

For the 21st century, Thompson Fullilove asserts, the problem is displacement. “African Americans and aborigines, rural peasants and city dwellers have been shunted from one place to another as progress has demanded, ‘Land here!’ or ‘People there!’ In cutting the roots of so many people, we have destroyed language, culture, dietary traditions and social bonds. We have lined the oceans with bones and filled the garbage dumps with bricks.”

The crucial question arising from all this, she posits, is “What are we to do?” And if current local efforts to reconsider redlining and urban renewal can’t yet answer that question, they’re at least helping focus attention on neglected aspects of this community’s history whose impacts are still being felt today. The recently dismantled UNCA exhibit will be on display in Pack Library’s North Carolina Room throughout May.

This has been a very informative article and I wholly agree with what it’s saying about urban renewal and it’s negative effects on the African American community. I want to say that I moved here in 1970 and at that time I was shocked. There was a street, I can’t remember if it was Valley or not, and for a long city block it had shacks on it. Seriously, buildings that looked like shacks . I’d never seen anything that looked like those houses. At that time the expose on these homes were that they had holes in their structure, were infested with rodents and the landlord did not care. I’m not sure when these were torn down but I don’t think it was until the late ‘’70’s. or where the renters of these terrible abodes were sent. Maybe it was the apartments built that were located by McCormick field, which at that time would have been a major improvement.

“The renters of those terrible abodes” were mostly sent to one of the city’s housing projects: Lee Walker Heights, Pisgah View, Deaverview, Hillcrest, or Klondyke. They were only supposed to be there until new homes could be built. The funds ran out. That was 50 years ago.

“Those terrible abodes” were home to the folks who lived there – and as rundown as some of them were, the Valley Street and Southside communities were united and self-policing, and was a part of the Asheville landscape. Besides houses, they contained garages, gas stations, stores, restaurants, schools, Churches, a major funeral home, etc.

Most of those folks were sent to live in the projects or went away to live with relatives – many of the older folks withered and died shortly after leaving what they knew – and the projects are more segregated from Asheville life than the old neighborhoods of Valley Street and Southside Ave ever were….

But at least the newbies got some nice wide streets they can look at instead of having their sensibilities offended by the sight of terrible abodes that real people lived in, and they are, of course, insulated from having to actually visit the “Hood” – and I reckon the projects look OK – from a distance, anyhow.

the Housing Authority of Asheville was first chartered in 1940, and now we have more public housing and subsidized housing per capita than any other city in NC…

HACA never works to downsize as their paychecks depend on adding more and more units for the poor takers. Remember it was socialist democrackkks who did all this…still is…

thats great that all you have is criticism, how about you offer a solution?

Oh I don’t know, stop expecting poor people to rise out of poverty by paying them to be poor?

Start mainstreaming the able bodied residents, shut down some of the public housing and only house the disabled and truly indigent! There is no reason

for AVL to be SO engulfed by SO much public housing that causes never ending problems for the rest of us daily! The Housing Authority of AVL

management should be ashamed to show their faces in AVL …

Oh, Fred Caudle has a solution alright, but you’re not gonna like it.