This story, originally published by Carolina Public Press, was jointly reported and edited by Kate Martin and Frank Taylor of Carolina Public Press; Gavin Off of The Charlotte Observer; Brian Murphy, Lucille Sherman and Jordan Schrader of The News & Observer; Nick Ochsner of WBTV; Emily Featherston of WECT; and Tyler Dukes of WRAL. Carolina Public Press is an independent, in-depth and investigative nonprofit news service for North Carolina.

In late March, Mary Wyatt was concerned about her husband, Frank. They’d been married 66 years and had moved around the country together as he pursued his military career and then worked in the state of Florida. Now they were retired in Cherokee County.

Mary Wyatt called the doctor, who was alarmed about his condition.

“He was running a fever and he was so sick,” she said of her husband. “The doctor said to bring him to the emergency room immediately.”

They ran every test imaginable on him, including one that checked for the new coronavirus, which causes COVID-19. They eventually learned he tested positive.

Four days later, Frank Wyatt was dead. He was 86 years old.

“He was so awfully sick when I took him to the hospital — and it happened so suddenly,” she said. “It was like a bullet being shot at you.”

In addition to losing her husband, Mary herself began feeling the effects of the virus.

“It can hit you any minute, and you won’t know it and then someone in your life is going to be gone, possibly you,” Mary Wyatt said. “And this illness from it — it’s unbelievable. There is nothing like it. And they are telling me that it is going to take me weeks and weeks to get well.”

In the end, the entire ordeal is distilled into just a few words: Frank Wyatt’s death certificate says he died of respiratory failure, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and a COVID-19 infection contributing to his death.

Death certificates leave questions unanswered

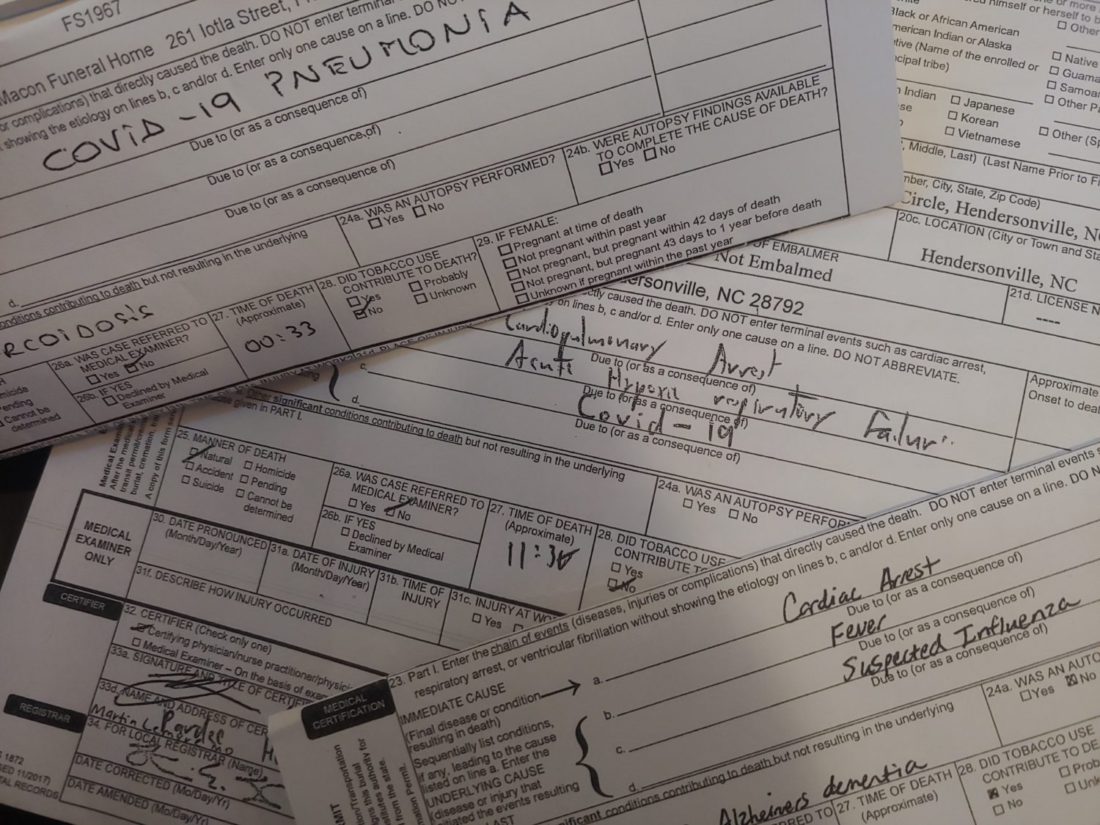

The death certificates for two groups of North Carolina residents who died in late March and early April within days of each other testify to what claimed their lives.

They suffered from a range of conditions that commonly are seen, singularly or together, in elderly patients approaching death — cardiopulmonary arrest, acute respiratory failure, pneumonia, coronary artery disease, COPD, atrial fibrillation, lung cancer and diabetes mellitus.

But the death certificates for the first group of these men and women — including Frank Wyatt — indicate an additional aggravating health factor, which likely proved fatal for their already struggling physical systems. They tested positive for COVID-19.

The other group of death certificates gives no indication that these people were ever tested, despite remarkably similar symptoms. After all, these conditions kill people every day.

Without the test results, whether negative or positive, it’s impossible to know how many of these North Carolina residents who died had the virus. And the number of people in North Carolina who died with comparable symptoms, but without any test results recorded, is many times greater than the number whose death certificates say they tested positive.

When state officials say 213 state residents have died of the virus as of Tuesday morning, they can only include those who tested positive. Those with the same symptoms but no COVID-19 test results aren’t included — even if a physician suspected the virus.

“Laboratory-confirmed deaths are reported by hospitals and physicians directly to the local and state health departments, usually within hours or days of a patient dying,” Amy Adams Ellis, spokeswoman for the state Department of Health and Human Services, said.

“These only include people who have had a positive laboratory test for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and who died without fully recovering from COVID-19. Laboratory-confirmed deaths are the deaths reported on the NCDHHS webpage.”

DHHS has acknowledged a second way to track COVID-19 deaths: death certificates. But a review of thousands filed in counties across North Carolina by a collaborative of reporters from six newsrooms found a range of factors that make the second method easier said than done.

The task of accurately tracking, counting and reporting COVID-19 deaths is further complicated by a continued shortage of tests.

Death certificates unclear even in laboratory-confirmed cases

In some cases, death certificates don’t mention COVID-19, even when the state has confirmed a patient’s positive results and is counting the death in its total.

That’s the case in Carteret County, where the death certificate of an 84-year-old who died in early April lists acute respiratory failure, adult respiratory disease syndrome and bilateral pneumonia as the causes of death. The state counts the case as the county’s first COVID-19 death after a confirmed lab result.

In Wayne County, where there have been at least six coronavirus-related deaths, no death certificates that had been provided by the county’s register of deeds as of Tuesday list COVID-19 as a cause or contributing factor to death.

When someone with COVID-19 dies in Wayne County, the hospital or other entity overseeing the patient’s care completes a discharge summary, which is then submitted to the county health department, said public information officer Joel Gillie.

Gillie said information about the deceased person is also entered into the N.C. Electronic Disease Surveillance System — the same way a positive COVID-19 test would be — which both the county and the state can then see.

The N.C. Office of the Chief Medical Examiner sent guidance to counties in late March, as the death toll started to climb, about how to account for COVID-19 on death certificates.

In that guidance, providers were told to not wait to confirm whether someone had tested positive for COVID-19 before issuing a death certificate and, if they were unsure, to list COVID-19 as a cause of death or contributing factor to someone’s death.

“As this situation unfolds, testing availability will be limited,” the chief medical examiner’s guidance said. “As such, in some situations, a provider may need to sign a death certificate for a patient whose viral infection status is unconfirmed. Best clinical judgment must be used regarding whether a patient is infected and that best opinion applied to the death certificate.

“While some may be uncomfortable with the notion of uncertainty, remember that in this setting, we as providers do not have the usual luxuries of getting confirmation.”

A major reason the chief medical examiner and other practitioners across the state are urging providers to be less than precise in filling out death certificates is the vital role a death certificate plays in recording deaths.

In some cases, that means results might still be pending when a death certificate is completed, said Dr. Jennifer Green, Cumberland County health director.

“We don’t want anybody to delay finding that death certificate because that test hasn’t come back yet,” Green said.

If a test is pending, she said, doctors and hospitals should know. And the certificates can always be amended later to list COVID-19 as a cause of death.

“Our understanding is that providers should be putting that information on the death certificates,” Green said of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

In her county, she said, there’s been frequent communication between her office and hospitals about how to count cases and deaths in line with the state’s guidance.

“We are not aware of any deaths where they have not been counted,” Green said.

A review of death certificates in Buncombe County found at least two that noted COVID-19 tests were still pending at the time the certificate had been completed. Buncombe health officials did not respond to a question about the results of those tests or whether they had counted toward the county’s COVID-19 deaths in time for this article.

COVID-19 noted on the death certificate, but death not counted

In other cases, the review of death records found that even when the coronavirus is noted on a death certificate, it doesn’t mean the person has been counted in the official tally.

As of Tuesday, Onslow County had just one reported virus fatality, despite two death certificates mentioning COVID-19.

One listed the virus as the secondary cause of death, while the other listed “Suspected complications of COVID-19.”

The register of deeds office said the latter was not being counted as a virus-related fatality because it was not a lab-confirmed case.

David Howard, deputy health director in New Hanover County, said the guidance from the state has been to only report deaths attached to lab-confirmed cases of the virus, leaving out cases where a physician has diagnosed someone with the virus or suspects the virus in absence of a test.

“Those will be counted; they are not being counted now because we are erring on the side of being accurate with our death reporting and our case reporting, as opposed to trying to extrapolate to a number of cases and a number of deaths across a community or a county or state,” Howard said.

How and when those will be counted remains to be seen, he said, because there is still much to be studied about how COVID-19 interacts with the human body.

“Some cases will be missed. I think mostly those cases that will be missed are the ones who are nonsymptomatic,” Howard said. “For persons who passed away, I think, given the urgency of the situation, not many of those are going to slip through the cracks.”

Howard said the lack of testing plays into accurately tracking how deadly the virus is.

Problem accessing death certificates

In North Carolina, death certificates are maintained by two separate agencies in each county: the county health department and the register of deeds.

State law requires both agencies to provide copies of death certificates in response to a public records request, according to Mike Tadych, a Raleigh lawyer who regularly represents members of the news media in records lawsuits.

But the collaborative found mixed responses from county health departments and registers of deeds across the state.

Within two days of journalists requesting death certificates from county health departments, officials with DHHS sent guidance to county offices advising them to not provide the requested records. DHHS did not cite any legal justification for the advice.

Elaine Russell, director of the Transylvania County Health Department, asked DHHS whether her office was the proper agency to provide death certificates to the collaborative.

“We don’t hold the official copy, so I don’t think we can respond to the request,” Russell wrote.

DHHS told Russell to send reporters to the state health department’s communications team instead.

“Because of policies and statutes that are put in place, the Health Departments are NOT issuing agencies and cannot issue ANY information as it pertains to birth or death,” wrote Floriece Davis-Jones, of the state’s vital records office.

As of Tuesday afternoon, DHHS had not responded to questions about why it advised county health departments not to release the records or what state law justified the agency’s guidance.

In Iredell County, a spokeswoman for the health department responded with similar pushback.

“Thank you for reaching out to us; however, it is our normal and ordinary business practice to refer anyone requesting a noncertified or certified copy of a death certificate to the Iredell County Register of Deeds,” spokeswoman Megan Redford said.

When a reporter asked what legal provision prohibited her office from providing the requested records, she could not provide one.

An attorney for the county later claimed the register of deeds was the only authorized custodian of the records, even though that provision is not included in either the Public Records Act or the law regulating death certificates.

Neither the Iredell County health department nor register of deeds has so far provided the requested death records.

Late Tuesday afternoon, the county’s register of deeds, Ron Wyatt, told a reporter he would charge for time his staff spent researching and pulling death certificates. Wyatt also objected to a reporter accessing the public records at all.

“I will be making everyone in Iredell County aware through various means available that you are wanting all these death records with their loved ones’ private information!” Wyatt wrote in an email. “As an elected official, it is relevant the public be aware of how you are trying to bully the county into just giving you info from private citizens because you think you deserve it.”

But other counties have readily and quickly produced records.

Johnston County provided death certificates electronically on the same day they were requested. The county provided two batches of records from March 1 through April 21. Five of the 192 deaths recorded during that period listed COVID-19 among the causes of death.

Reporters had similar experiences in counties across the state, including Burke, Buncombe, Scotland, Onslow, New Hanover and more than a dozen other counties. Hyde County provided its single death certificate for the requested time frame in less than an hour. Buncombe gave a reporter access to its online database, which is itself a public record under state law.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.