Some died in landslides and cave-ins. Others perished due to malnutrition. Several were shot down while attempting to escape. The exact number of incarcerated individuals who lost their lives during the construction of the Western North Carolina Railroad is unknown.

What historians do know is that the rail link connecting WNC with the eastern part of the state would not have been completed without those prisoners’ backbreaking and often deadly labors. Yet today, the hundreds of former slaves who endured unspeakable hardships while helping lay tracks and excavate seven tunnels with a total elevation gain of 1,100 feet are largely forgotten. And at least 139 of their bodies are believed to lie in unmarked graves between Old Fort and Ridgecrest, says UNC Asheville history professor Daniel Pierce.

Some skilled laborers were hired for the project, and Black women did laundry and cooked, but most of the workers were African American men serving lengthy sentences for petty crimes like theft and vagrancy.

“For a significant portion, this turned into a death sentence,” says Pierce.

To commemorate their efforts and spotlight the history of those overlooked Americans, Pierce recently teamed up with 10 other local historians and community members to form the Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee.

“There has been so much talk about taking things down,” says Pierce, referring to the ongoing removal of Confederate monuments across the country. “Another part of the conversation, though, is what do we put up.”

On Aug. 10, the Old Fort Board of Aldermen approved the Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee’s plan to design and install a memorial at Andrews Geyser, a 19th-century tourist attraction that’s not far from the train tracks. “There’s been real enthusiasm about it,” Pierce reports.

Nonetheless, he recognizes that not all community members will be on board with the project. “Some people will react with ‘Why do you want to recognize convicts?’” the historian predicts. But that attitude, he maintains, overlooks the fact that the punishment didn’t always fit the crime.

Meanwhile, other local historians point out that many now view the convict leasing system as the South’s attempt to re-create slavery under a different name in the wake of emancipation. Although the practice existed before the Civil War, it expanded substantially during and after Reconstruction.

More brutal than slavery

In a 2001 Appalachian Journal article titled “Zeb Vance and the Construction of the Western North Carolina Railroad,” historian Gordon B. McKinney outlined the challenges and delays the state faced during the railroad’s westward expansion toward Asheville. This included disputes over its route in the 1850s, the Civil War in the 1860s and the subsequent mismanagement and misuse of state funds during the early years of Reconstruction.

In 1876, however, former wartime Gov. Zebulon Vance was once again running for office. One of his campaign promises was completing the railroad, and after reclaiming the governor’s mansion, Vance aimed to honor that commitment regardless of the human cost.

“The use of convict labor was becoming a standard practice throughout the South during this time period,” McKinney wrote. “By placing the convicts at work sites, the Southern states eliminated many of the costs of maintaining the prisoners in prison buildings. This practice also allowed the state to make investments in projects — through labor — without the use of scarce money.”

According to McKinney, the railroad’s daily cost per prisoner was 30 cents; in 1878, the standard cost of labor was about $1 a day. That December, he noted, despite malnourishment and an unusually cold winter, 558 incarcerated laborers began working on an unrelenting schedule that ran uninterrupted for nearly 90 days, with time off only for Christmas and a single day in February.

“Their lives were not worth anything except for labor,” says Anne Chesky Smith, executive director of the Western North Carolina Historical Association and a Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee member. “And they were easily replaceable, because [the state] could pick up and sentence people to work on the railroad for minor crimes.”

Fellow committee member Darin Waters, an assistant professor of history at UNC Asheville, agrees. “In many ways, the convict leasing system was much more brutal than the slave labor system,” he says. Previously, owners had viewed enslaved people as significant financial investments, Waters explains; incarcerated workers, on the other hand, cost little or nothing and thus were expendable.

As Waters documented in his 2012 doctoral dissertation, between 1876 and 1894 North Carolina’s Black prison population more than doubled, from 676 to 1,623. “Along with racism,” wrote Waters, “the continued demands for a cheap supply of labor, especially for railroad construction, was a major reason for the increase in the number of Black inmates in North Carolina.”

Convict or victim?

When it comes to reexamining the past, historians frequently encounter a similar roadblock: Most people simply don’t know much about history. Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee members, though, are quick to note that our region’s collective lack of awareness of the exploitative and inhumane conditions that incarcerated laborers faced is understandable. Even at the time, few considered convict labor a story worth documenting, much less memorializing.

“The biggest thing for people to keep in mind as we’re talking about this is how even the use of the word ‘convict’ is problematic,” says Waters. Many of those forced to work on the project, he says, were either falsely accused or faced trumped-up charges for minor offenses. But once people were labeled convicts, society viewed them solely through that lens.

Pierce agrees. “There was a tendency not to question that those arrested were legitimate convicts,” he says. Both historians add that things haven’t changed all that much today.

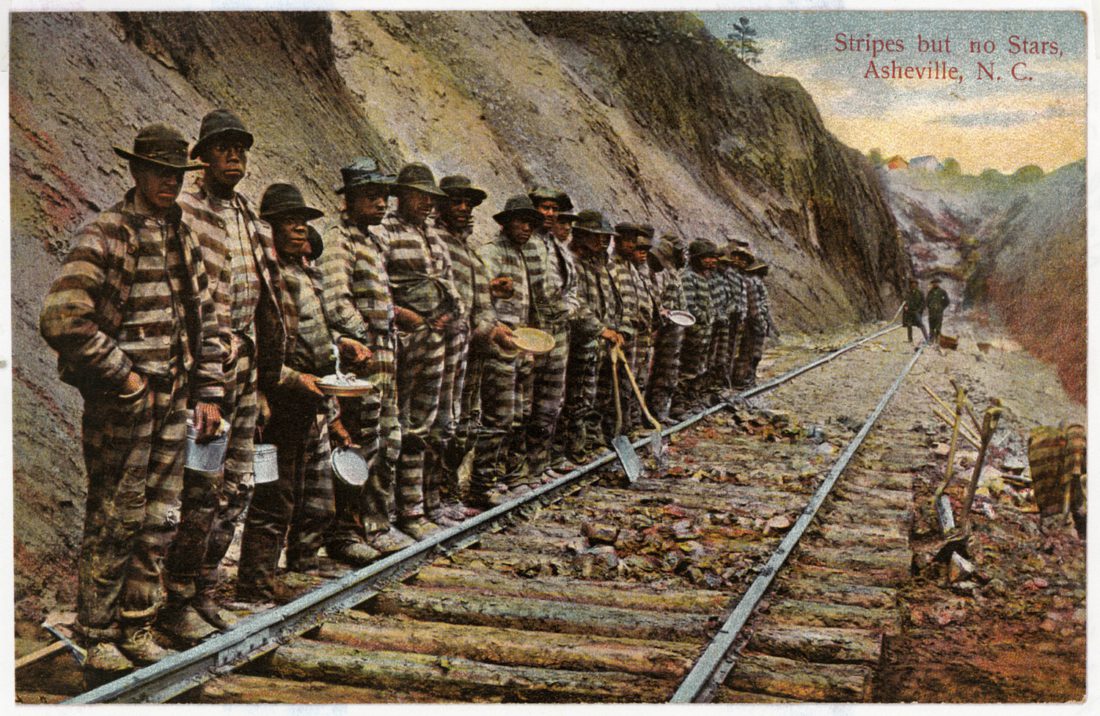

And what little information the public did receive about these men was designed to further humiliate and dehumanize them, Pierce contends. A popular postcard from the period shows incarcerated workers lined up along the tracks. In the background stand two men, one holding a shotgun. The message across the top reads, “Stripes but no stars, Asheville, N.C.” The postcard, Pierce points out, was considered good fun; the unknown men depicted were viewed only as a joke, not as human beings.

Encouraging empathy

Now, however, the Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee hopes to right this wrong. Although the project is still in its early stages, the group is hard at work on design concepts for the memorial and ideas for fundraisers, hoping for a spring 2021 dedication.

“We often marvel at the powerful men who engineered the railroad without giving much thought to the people who, for the most part, were forced to unwillingly do the actual labor,” says Chesky Smith.

“It’s important for us all to begin to understand the scale of human exploitation that occurred to connect Western North Carolina to the rest of the state by rail,” she continues. “And also to hopefully create a sense of empathy for how impossibly difficult it would have been to be imprisoned on this mountain — away from your family, doing hard labor with little nourishment, locked into boxcars at night — potentially for a crime you did not commit, with little hope of finishing out your sentence [alive] and returning home.”

To learn more about the Railroad Incarcerated Labor Memorial Committee project, visit avl.mx/8a5.

Great article, Thomas.