A series of photographs changed everything for Honey Simone, a local entrepreneur and artist. She discovered the images at the Buncombe County Special Collections, formerly known as the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library.

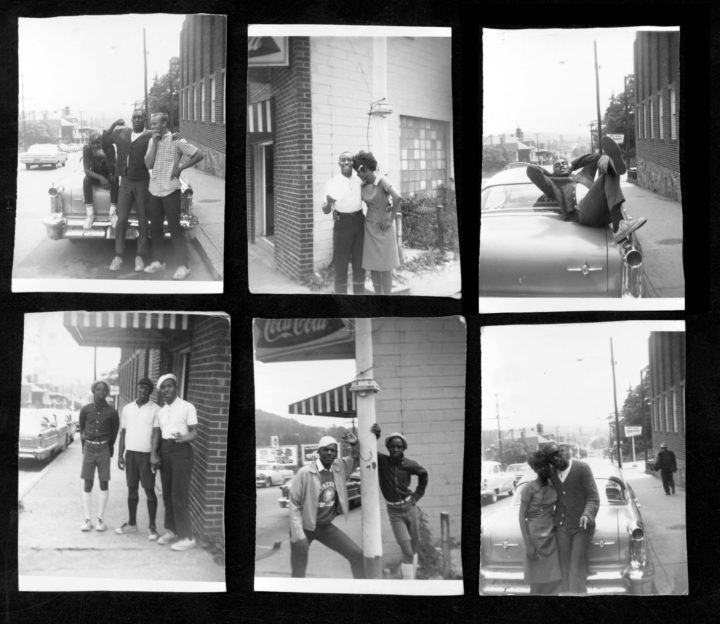

The first set of pictures, taken in the 1970s outside The Orange Peel, capture a group of Black youths in various poses — some are leaning against cars, others are flexing biceps and a few couples shyly embrace for the camera.

Another photograph, also from the 1970s, shows local saxophonist Cliff Cotton performing alongside another Black musician, whose identity is unknown. And yet another image, taken sometime in the 1940s, reveals a younger Cotton with his aunt Iola Pearson Byers smiling in front of the Rockefeller Memorial on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

“It changed my life, seeing those photos,” says Simone. “It was one of the first times that I experienced seeing Black history that wasn’t based in trauma.”

In March, Simone became the first artist-in-residence at Engaging Collections, a local nonprofit launched in 2019 by Lydia See. The organization connects artists of color with North Carolina-based libraries and archives to create a more welcoming and diverse space for people of color. The Buncombe County Special Collections, managed by Katherine Cutshall, is the organization’s first partnering institution.

Throughout much of Simone’s residency, the BCSC was closed to the public due to COVID-19. The downtime allowed the team to reimagine the room, which is located on the ground floor of Pack Memorial Library in downtown Asheville.

Nearly a year later, the BCSC is scheduled to reopen this month at limited capacity. Simone, See and Cutshall hope the special collection’s new layout and interactive features spotlighting local African American history will create a more inclusive and inviting space for all community members.

“It’s about making sure that the people know that it’s here,” Simone says. “And making sure it represents the community we live in.”

Everybody’s responsibility

The irony of BCSC’s present-day mission is not lost on those involved in the project. Inclusivity is in many ways the opposite of the original vision for the room.

According to Cutshall, the collection formed in 1931, when Foster Alexander Sondley, a prominent local attorney and historian, bequeathed his expansive personal library to the city of Asheville, which later donated it to the library. Among other stipulations, Sondley required the items be accessible only to nonsmoking, white residents of “upstanding character.” Archivists honored that requirement for three decades before the library system’s integration in 1961.

Today, the collection has expanded far beyond Sondley’s original donations — a large portion of which was sold to Chapel Hill Rare Books in 1987. Still, the legacy of white supremacy has clung to the collection for decades, an exclusionary perspective not unique to the BCSC.

Whiteness, says See, dominates many archives. “The people who select what is qualified as enduring historical value often look like the people they identify as having enduring historical value,” she explains. “So cisgender whiteness begets more cisgneder whiteness begets more power and so on.”

Encountering a predominantly white collection, notes Simone, alienates community members of color. She recalls her own frustration upon first visiting the BCSC and struggling to find documents reflecting nonwhite experiences.

“I didn’t really see myself in this place,” she says. “And that’s a common experience for a lot of Black Americans. You just never really see yourself in places where you want to see yourself.”

Only after extensive research did she locate the images that altered her perspective on the collection and her new role in it. But that didn’t erase past experiences. Nor did she see her residency as the singular solution to a history of white supremacy.

In 2021, Simone explains, “It’s everybody’s responsibility to highlight Black and Indigenous history. This crusade of knowledge shouldn’t be something that we’re waiting for a young Black woman to lead us into.”

Carolina Record Shop

Nevertheless, Simone has helped pave the way for a more comprehensive collection through her interior design of the new space, which aims to encourage younger and more diverse participation. Her main contribution is the creation of the Carolina Record Shop — an area equipped with a turntable and records and furnished in the style of a 1970s living room.

Records pressed in Asheville dominate the shelves, but not all sleeves house actual vinyl. Instead, some feature scanned documents from the archive’s collection, revealing records of another sort with an emphasis on the city’s history of Black music and art, including vocal duo Pic and Bill (Charles Pickens and Bill Mills) and soul singer Willie Hobbs, among others.

Accessibility and demystification were the dual impetuses for presenting images and articles typically stored in stacked boxes in the collection’s back room in a new way. Too often, says See, gatekeeping — intentional or not — creates barriers that discourage individuals from entering, much less exploring, the materials held in a given archive or special collection.

By contrast, Simone’s design creates a recognizable and welcoming space. And with music, which will be played throughout much of the day (except during designated research hours), the Carolina Record Shop reimagines how a special collections room should look and sound.

Meanwhile, additional artists from Different Wrld, a creative hub and collective that Simone launched in 2016, is helping to create an illustrated timeline that will stretch across the room’s back wall.

An incredible gift

Time never stops. That’s something historians and archivists are keenly aware of. Just as the past was once the present, the present will inevitably become the past. By demystifying the BCSC and creating a more welcoming space, the project’s designers hope future generations will discover a more comprehensive collection of today’s history-in-the-making.

“Our bodies are archives,” says See. “That means everybody is an archivist. And that’s especially important right now. We are all collectively responsible for preserving our lived experiences through this traumatic time to ensure that in the future when somebody reads a history book, this period isn’t just an offhand one-liner.”

Though the task may seem daunting at first, Simone lists ways we already gather and record our histories. “We archive on our Instagram every single day,” she says. “We archive on our Facebook. We have archives of our families in photo albums on our coffee tables. And you can literally take these photos to the Buncombe County Special Collections and get them digitally scanned and put into history to ensure it will be there for future generations to see. That’s an incredible gift.”

And it’s a gift Simone herself recently contributed to unintentionally.

“I was protesting all summer,” she says, in response to the police killing of George Floyd. “I was fighting for my life.”

As Simone marched for racial justice, Cutshall put out a call on social media asking residents to share images from the events with BCSC.

“And now there is a picture of me leading our city into protest in our archives,” Simone continues. “I can see myself in the collection.”

But her work is far from over, Simone notes. “It’s about making things more accessible. It’s about breaking things down. It’s about making the world a better place.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.