Can rising gun violence in Asheville be stopped in its tracks by roughly $200,000 of funding supporting a year of on-the-ground programming? Probably not. But that doesn’t mean community organizations don’t plan to try.

Over the last year, the urgent need to address the interrelated causes and impacts of gun violence, systemic racism and poverty grew even more pressing. In 2020, the Asheville Police Department reported a five-year high for calls related to gun discharges and shootings, the vast majority of which involved Black men. Community members grew tired of witnessing the disproportionate impact of gun violence on their friends and neighbors, explains Tiffany Iheanacho, Buncombe County’s justice services director, prompting county leaders to look for new solutions.

In June, Buncombe County’s child fatality review team identified gun violence as a growing threat to children in Asheville. Buncombe County’s Justice Resource Advisory Council passed a proclamation declaring racism a public safety emergency in July.

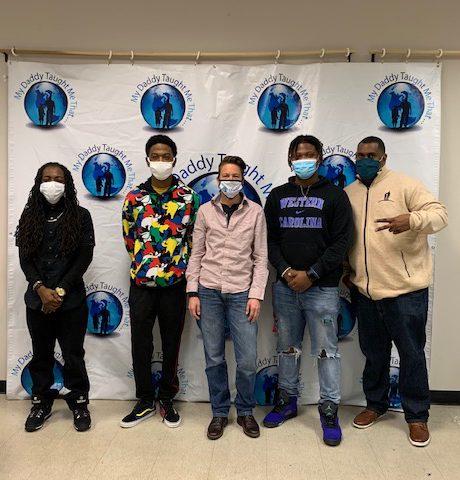

In early January, Buncombe County announced a new partnership with four community organizations — the SPARC Foundation; Umoja Health, Wellness and Justice Collective; My Daddy Taught Me That; and the Racial Justice Coalition — to develop a community-led strategy to help address gun violence. Funded using a portion of the county’s $1.75 million Safety and Justice Challenge grant, which aims to reduce jail populations, the team plans to provide residents comprehensive services to support the journey out of poverty and trauma.

“In this day and age, it’s really hard to come up with a novel idea about anything,” says Jackie Latek, executive director of the SPARC Foundation. “What we’re doing here is taking existing programs that have evidence and research behind them that have worked, and we’re pulling those programs together.”

Tough nut to crack

Enter the newly formed Violence Interruptors Street Team. The goal is to shine a light into one or two neighborhoods overwhelmed by gun violence, Latek says, with each partner organization tackling a different systemic problem that could lead someone to commit violence.

Her organization, the SPARC Foundation, will work to develop pathways to financial stability and connect residents to medical resources. Umoja Health, Wellness and Justice Collective, under the guidance of Michael Hayes, will focus on resolving community trauma through multiday resiliency training and listening circles. Community members will be trained as Umoja facilitators, explains Hayes, the organization’s executive director, ultimately becoming a resource for healing in areas facing the greatest challenges.

Student ambassadors from My Daddy Taught Me That will build relationships with young people in the targeted communities (which haven’t yet been selected), says MDTMT founder Keynon Lake. The youths’ role will be as “boots on the ground,” working to teach conflict resolution skills and share the many opportunities available to youths in Asheville and beyond.

Connecting with individuals committing gun violence is a tougher nut to crack. That’s where the Racial Justice Coalition comes in, says community liaison Rob Thomas. While the other partner organizations are out in the community, he’ll be identifying programs that have demonstrated success at reducing gun violence elsewhere and creating a proposal detailing what it would take to implement something similar in Asheville.

The group points to Operation Peacekeeper, a Stockton, Calif.-based initiative that employs “street-wise” individuals trained in conflict resolution, mediation and mentorship to work with young adults at highest risk of gang involvement and gun-related violence. A 2002 study of the Operation Peacekeeper model by Harvard University researcher Anthony Braga found a 42% decrease in monthly gun homicides, compared with pre-intervention trends.

The grant establishes a hierarchy that shares decision-making power equally among all partners. Keeping the focus on community leadership, rather than law enforcement, is key to building neighborhood trust, Latek says. “For the county to put money towards an initiative to address gun violence without it being police-focused, that’s new in my mind,” she says.

‘Left unchecked’

In 2020, the Asheville Police Department responded to 10 homicides within city limits, says department spokesperson Christina Hallingse. Eight of the victims were Black men. The weekend of Thanksgiving saw seven shootings over three days; on Nov. 30, a 17-year-old was killed in a shooting in Montford.

Gun violence is a “serious public health crisis” that the APD takes very seriously, Chief David Zack wrote in a statement to Xpress. “Working with community members and partner organizations is imperative to develop and implement a successful gun violence reduction strategy,” he said.

But the impact of the violence continues to disproportionately fall on people of color, says Lake of MDTMT. “There has been a blind eye to this. We haven’t had the proper responses from law enforcement or our local government, so you’re left with a group of people left unchecked and not properly cared for.”

In 2019, Black people comprised 25% of the Buncombe County Detention Facility’s population and 69% of gun-violence victims, despite representing only 6.3% of the county’s population. In early 2020, justice system staff worked to reduce the number of people incarcerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even as the number of those detained went down by nearly 40%, however, racial disparities intensified. By July, the jail’s Black population had risen to 33% of the total.

Stopping gun violence before it occurs is critical to keeping jail populations low, Iheanacho explains. Gun violence episodes often trigger higher-level felony charges, which take longer to prosecute. Judges are less likely to release individuals charged with violent offenses on bail pretrial, she adds, leaving more people in custody as they wait for their day in court.

That said, violence isn’t confined to gun use or to predominantly Black communities, explains Grits, a member of the Racial Justice Coalition. Though domestic violence, intimate partner violence and sexual violence exist in every community, when white people hear the word “violence,” they automatically and unfairly think about neighborhoods of color, the activist posits.

“We continue to write off this demographic and say that they’re all violent,” Grits says. “And then we put forth these ‘solutions’ that are largely law enforcement-based from folks who don’t live in the community, but we’re not redistributing resources to ensure folks can get out of bad situations.”

Uphill push

Change isn’t going to happen overnight, leaders caution. Mentorship programs can take years to show shifts in mindsets, Hayes says, and repairing generations of trauma will likely require decades of work.

From redlining to predatory lending; from the era of mass incarceration to the enormous achievement gap between Black and white students enrolled in Asheville City Schools, gun violence cannot be solved without understanding the history of racism that drove many Black communities into poverty, Thomas argues. “You have to understand the history so the solution will not be seen as charity, because the solution will require a lot of resources, from people to money to infrastructure,” he says.

Residents in communities experiencing high rates of violence are likewise tired of watching programs come and go within a few years, Latek adds, making continued county support all the more important. “If we’re going to push this rock up a hill, don’t pull our people away from us when we get halfway up,” she says. “We need to get this rock to the top, before it comes crashing back down on us.”

Buncombe County hopes to continue funding the program after its first year, says Hannah Legerton, the Justice Services grants manager. Staff has applied for an additional year of Safety and Justice Challenge grant funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; if awarded, the renewal includes a one-year program extension. Longer term, the county is beginning to look for outside funding streams to continue projects that have demonstrated success, she says.

If the city of Asheville wanted to get involved, Thomas suggests using a portion of the Asheville Police Department’s $30.1 million annual operating budget. As activists continue to advocate for a 50% cut to the APD budget, a fraction of that funding for a program like this could have a huge impact, he says.

“Gun violence isn’t just a Black-person thing, it’s not just a poor-person thing, it’s an everybody problem — you could get shot or robbed if you’ve been doing everything right in your life,” Thomas says. “With this program, we’re trying to work a miracle with a hope and a wish.”

Ok, black people shooting black people, maybe us people with guns that aren’t in cities aren’t the problem, and biden’s plan is stupid…