In 1997, Leni Sitnick started campaigning for mayor of Asheville on a platform that included a focus on the local economy.

“It was my idea that we should support the businesses that already exist in Asheville and help them thrive and survive, and to look at Asheville’s existing strengths and try to promote things that were successful,” Sitnick says. “One of those things was the magical and wonderful history that already existed for Asheville and Western North Carolina in the movie industry.”

Fresh off the filming of My Fellow Americans (1996), the area previously welcomed such famous productions as The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and The Fugitive (1993), and was home to numerous behind-the-scenes professionals. What was lacking was something to help bring these various industry components together and celebrate their accomplishments while continuing to enhance the region’s draw.

Street credentials

Sitnick was elected to office that November and says Asheville City Council and various municipal departments supported pursuing ways to elevate the local film community. A few years later, Melissa Porter, then festival director for the Asheville Parks & Recreation Department, was invited by her sister-in-law, who was living in Utah, to attend the Sundance Film Festival in Park City.

“I went out there and absolutely fell in love with the town and the look of it and what they were bringing to Utah and the thought process behind it,” Porter says. “And I was like, ‘This so could be Asheville.’ I could just feel that energy that we could do something really great.”

Porter, who also coordinated the Bele Chere summer festival, ran the idea by Asheville Parks & Recreation director Irby Brinson. He encouraged her to meet with community members, then write a strategic plan and create a budget to take before City Council.

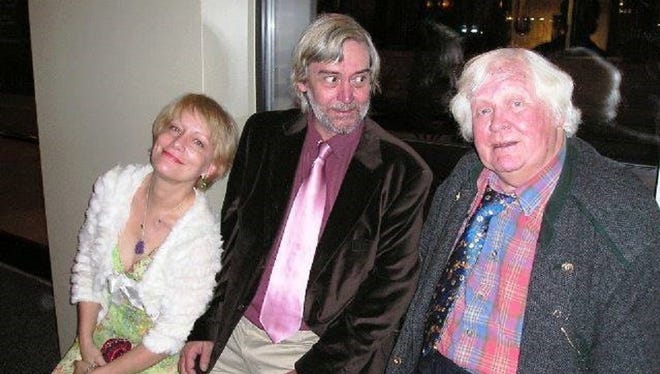

The proposal was approved and, with guidance from economic development nonprofit AdvantageWest’s WNC Film Commission, Porter assembled a festival advisory board composed of local film industry members, among them film and television production veteran Lee Nesbitt Madison. Other key figures involved in steering the festival included John Cram and Neal Reed of the Fine Arts Theatre, former Xpress film critic Ken Hanke and the marketing team of Steve Lutz and Kathi Petersen.

The multiyear process resulted in the inaugural Asheville Film Festival in 2003, which Sitnick and Porter recall as being an exciting, multiday event at numerous downtown venues, culminating in an awards ceremony at Blue Ridge Motion Pictures, housed in the current Highland Brewing Co. complex. AFF’s early success soon attracted such notable filmmakers as Ron Howard (2004), Ken Russell (2005) and Don Mancini (2005-07).

Meanwhile, one of the city’s most famous celebrities also partook in the festivities.

“At the time, Andie MacDowell lived here and she was involved from the beginning,” Porter says. “We were able to use her name to get street credibility in a national and regional way.”

Following the inaugural AFF, the city hired Western Carolina University’s Center for Regional Development to survey the 8,000-plus attendees. Of the 635 people who responded, 388 reported spending an average of $133 per day. Eighty-three stayed in local hotels, spending an average of $119 per day for lodging. Though festivalgoers’ chief complaint was that many films were sold out, almost all stated they planned to return for the 2004 event.

Brief but memorable

In hindsight, Porter believes that AFF was somewhat ahead of its time in that it lacked the budget to become a true destination film festival. Funding hovered around $90,000 from 2006-08, then dropped to $67,400 in 2009, part of a 30% overall decreased budget for the Festivals Fund, partly prompted by the economic recession. In turn, Porter feels that it grew more difficult to maintain year after year; especially after she left her job at the city in 2008, and Nesbitt Madison stepped down as advisory committee chair the same year, both prior to that year’s festival. Nevertheless, Porter is proud of the work that she and her collaborators put into it.

“There’s a handful of events that I look back on with such strong memories and bonds,” says Porter, now a managing partner at Asheville Event Co. “Like so many other people in the community, I gave a lot of my time and vision to that event.”

Asheville had also evolved over that time. In tandem with dedicated entrepreneurs, downtown Asheville was thriving — to the point that, according to Porter, Bele Chere was causing many business owners to lose money instead of attracting customers. The summer festival became increasingly difficult to program from a political standpoint and ended after its 2013 edition.

Meanwhile, AFF had its own issues. Despite programming some of its highest-profile films yet, including awards season darlings Slumdog Millionaire and The Wrestler, the festival continued to lose money in 2008 — as was the case each year — and various partners expressed frustration at its organization under the new city leadership of Superintendent of Cultural Arts Diane Ruggiero.

An early 2009 Xpress report depicts a festival on its last legs with attendance down and organization in disarray. Hanke bemoaned a perennial lack of planning, stemming from the absence of a full-time festival director, and the event taking a back seat to Bele Chere each year. And Orbit DVD owner Marc McCloud proclaimed “the whole thing has been botched,” pointing to an emphasis on parties and celebrities over quality films.

In June 2010, citing fiscal responsibility, City Council voted 6-0 to cease funding AFF. After a year hiatus, AFF officially concluded its run in 2011 with a one-day, free event where locally made national releases Patch Adams, 28 Days and In Dreams were screened.

“It was a really good opportunity and it had a real economic impact. There were people that came and stayed, and it was a destination — and this is before the big beer boom,” says Reed, now the director of operations for the Fine Arts’ parent company, New Morning Ltd. “But the economic development goals aren’t the same, and our current environment of tourism and being a destination for things has changed.”

Torchbearers

Multiple local film festivals have come and gone since AFF concluded. The former Carolina Cinemas Asheville (now The Carolina Cinemark Asheville) hosted the indie-centric Ricochet Film Festival in 2010 and the genre-focused ActionFest, 2010-12. The latter event brought such action stars as Chuck Norris and Gina Carano to town for career achievement awards before shifting to a monthly series in 2013, ultimately its final year.

Area filmmakers Sandi and Tom Anton, who wanted to buy AFF, launched the Asheville Cinema Festival in 2011 and used connections with The Weinstein Co. to program local premieres of such future Academy Award winners as The Artist and Silver Linings Playbook. The event was last held in 2014. There was also a noncity-sponsored Asheville Film Festival, which ran 2016-18 at A-B Tech and screened small independent films. Each festival ended without explanation.

Current active offerings include the Asheville Jewish Film Festival (which began in 2009); Cat Fly Film Festival (2017), which supports up-and-coming indie filmmakers across the Southeast; and Connect Beyond Festival (2018), which uses music, film and storytelling to help forge bonds among creators. Asheville also attracts popular one- or two-day traveling adventure film festivals (e.g., Reel Rock and the Fly Fishing Film Tour) that consistently sell out spaces like Diana Wortham Theatre and Highland Brewing. The Fine Arts Theatre hosts AJFF and Connect Beyond, and Reed believes that such small, grassroots events are the future of film festivals.

“Studios and studio film, even in the last 20 years, has changed so much. And what we now call ‘independent film’ has changed so much,” he says. “We have filmmakers now that make films with phones. With a MacBook Pro, a good camera and a few thousand dollars, you can make a stunning film, so the definition of film and the structure of film and the way films are made has changed and is evolving.”

In addition to the democratization of filmmaking, those creators can now get their work to a larger audience at a vastly reduced price thanks to the rise in on-demand streaming. Reed sees the increased access as “nothing but a good thing” for everyone who loves quality films but he misses the purity of sitting in a theater and watching an image projected on a screen that’s produced by light passing through a celluloid reel. He notes that experience was all but nixed in 2012 when studios switched to a digital distribution model, a move that he says killed 30% of independent theaters — and has prompted several digital-averse cinephiles within his friends circle to stay away from theaters ever since.

“Add COVID to this mix, and now you’ve got people that don’t want to go and spend time in a room with other people, and then people of a generation that have no understanding of a shared reaction to a film — that laughter in a room,” Reed says. “Film festivals were originally ultimately tied to theaters, and so with that changing dynamic, if there’s no need to go to a theater to see a film, then why is there a need to go to the theater to see a film for a film festival?”

Along with their traditional in-person screenings, Sundance, the Toronto International Film Festival and other premier North American fests now offer digital programming, allowing interested parties to view films from home. And while numerous film critics and movie lovers continue to spend upward of a week hopping between theaters, subsisting on street food and watching films from 8 a.m. until beyond midnight — as Reed did for many years at TIFF — the theatrical exclusivity that film festivals once offered has dwindled, and, in turn, the interest in engaging in such activities.

“It was just so much different when a movie theater was the place to watch a film,” Reed says. “And that’s the big aspect that you can quantify and say it’s not the case anymore.”

For self-proclaimed “movie freak” Sitnick, the shifting paradigm likewise feels like a loss. The rise in ticket costs have resulted in her rarely going to theaters in recent years, and though she’s attended one screening during the pandemic, the atmosphere barely resembled the days before home viewing became a viable alternative.

“There were two other people in the theater,” she says. “With all of the opportunities on TV, and Netflix and Google, and streaming this and streaming that, the theaters are suffering. But the industry continues.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.