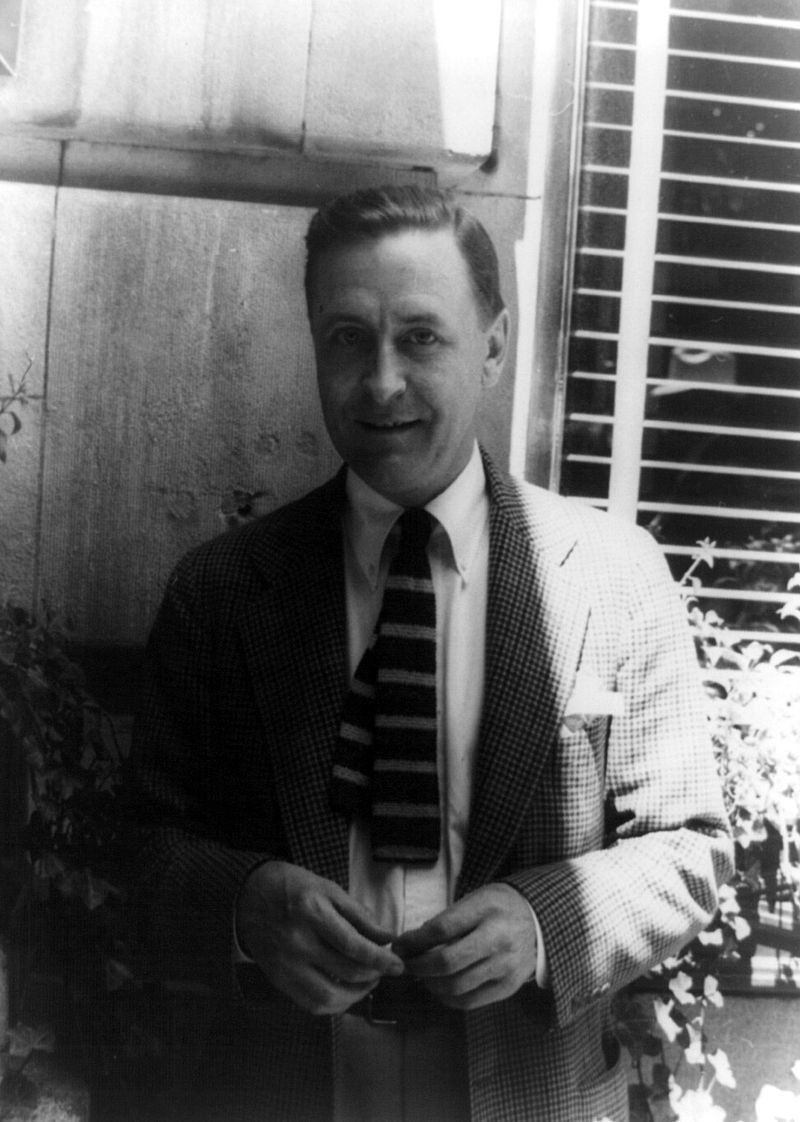

In 1936, while staying at the Grove Park Inn, a series of unfortunate events unfolded for writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. He arrived in Asheville to help transfer his wife, Zelda, to Highland Hospital where she sought psychiatric treatment. Later that summer, Fitzgerald dislocated his shoulder while diving into Beaver Lake (back when an actual diving board stood in the middle of the lake). By September, New York Post writer Michel Mok visited with Fitzgerald and wrote an article on him titled: “The Other Side of Paradise, Scott Fitzgerald, 40, Engulfed in Despair.” After the article appeared, Fitzgerald attempted suicide.

Years later, Professor Arthur Mizener would publish, The Far Side of Paradise – the first biography on F. Scott Fitzgerald. The book would be credited for reviving interest in Fitzgerald’s fiction. During his research, Mizener contacted Asheville resident, Martha Marie Shank, who had been hired as Fitzgerald’s business manager during his 1936 stay.

Shank’s letter is written 13 years after the events she’s describing, when she is 63 years old, retired and living in her Jefferson Apartment on Merrimon Avenue. Below are excerpts from Shank’s correspondence, recounting her time with the man responsible for such books as This Side of Paradise (1920), The Great Gatsby (1925) and Tender is the Night (1934).

Thanks, as always, to Pack Memorial Library’s Special Collections, North Carolina Room for its assistance.

On Oct. 26, 1949 Martha Marie Shank wrote:

…In October, 1936, I was called to Grove Park Inn to do some stenographic work for “a Mr. Fitzgerald,” but did not know until I got there that it was Scott Fitzgerald. I had read some of his books but knew nothing about him personally, and was surprised to find such a young man. At that time he had pretty well recovered from his shoulder injury which he told me he had received in a swimming pool accident. A nurse was with him, about whom I shall say more later. In the very beginning I did not know he was drinking. Had I known, and the extent, I should probably have quit right then. I soon learned that he was an alcoholic, but by that time I was sufficiently interested to stay on. Here I will say that at no time was he offensively or obnoxiously drunk, in the ordinary sense of the word, though I presume there was no time during his stay here that he was not under the influence of liquor. At first he tried in numerous ways to shock me, but when I didn’t “shock easy” he gave that up. For instance, he immediately began calling me by my first name, apparently to see how I would take it. I took it by calling him Scott, and from then on it was “Martha Marie” and “Scott.”

You say you know he came here because of an attack of tuberculosis and had been sent to Dr. Ringer (not Ringler) by Dr. Baker. This may be true. He told me he came to Asheville in order to put Zelda in Highland Hospital. I know he had tuberculosis and was treated by Dr. Ringer, but this treatment had ceased when I first knew him. …

You say that he had been drinking very heavily for some years. In all his conversations with me on this subject he gave me to understand that he had not, for any great length of time, been a drinking man; that he had taken his writing very seriously and worked hard and that his heavy drinking was relatively recent. I have no period of time in mind; but according to him, his wife’s mental illness and his own crack-up, or loss of ability to write were the causes of his drinking. At that time, I thought the drinking was an effect, but now I am not sure. I am sure, though, that he felt his writing ability had left, or was leaving him for good.

He brooded on this, and tried so desperately hard to write, and the result was largely trash, as he well knew. He wrote and re-wrote and re-re-wrote some stories, none of which was much good. … There were periods when he was trying to write and considerable lengths of time when he made no attempt. When he did try, it was more or less in a frenzy. There was much more time, I should say, when he was making no effort than when he was. He spoke of the reaction to his published articles on “cracking up,” and was a little amused by it. My fellow townsman, Tom Wolfe, was one who wrote and berated him and there were others.

The stenographic work I went to the Inn to do soon amounted to little or nothing – he wrote only the most necessary business letters and a very few personal ones, the latter being chiefly to Scotty [Fitzgerald’s daughter]. But he liked to have us there and as I had a good assistant in my office I did stay with him a good deal. Practically all the time I was there he had a nurse whom I will identify as Dorothy. She was very good for him, I thought. She was young (possibly 30) and attractive, but very level-headed. She was intelligent and compassionable, and I must say the three of us had some very good times! Sometimes he was gay and talkative and utterly charming. At others he was tragically depressed. Meals were sent up to his rooms and Dorothy and I did our level best to get him to eat, but I never saw him take more than a few bites. Apparently, he lived on gin and beer – that is what he drank all the time I was there. I have no idea how much gin he averaged a day, but it was plenty.

Next week we will continue Shank’s letter on Fitzgerald.

As always, I love this series of articles.

Writers who drink-who would’ve ever thought?

Even during Prohibition.

All the characters from The Great Gatsby except the narrator as well as anybody who visits the Grove Park Inn make me want to drink heavily too.

Enjoy reading your articles.

Love these letters and articles you are writing!!

Very interesting. I’ve heard that when Zelda Fitzgerald was a patient at Highland’s Hospital, she’d sometimes visit with Thomas Wolfe’s mother, Julia, at her boarding house in Asheville & that they’d sit on the porch & they became good friends. Zelda was a Southern girl, from Montgomery, Alabama, and I’ve always felt F. Scott Fitzgerald’s writing had a Southern flavor to it, probably due to her influence. Zelda wrote one novel, herself, called “Save Me the Waltz.”

I know she stayed there briefly in 1943. She wrote a letter describing her desire to leave. “The house is so dirty I think it best to go before atrification sets in. It seems remarkable that the vitality and inclusive metaphor and will-to-live of Wolfe’s prose should have known these origins.”

The last time I toured the Wolfe house, the guide actually pointed out the room in which Zelda stayed for a short time. Apparently, Zelda believed the boarding house was beneath her.

Mr. Richard Hurley (former HR director for Square D) once told me that his dad was working as some kid of aide or secretary for Mr. Fitzgerald during his stay in Asheville and was with him when he injured his shoulder. He improvised a sling using a typewriter ribbon, and he still had a thank you note from Fitzgerald to Mr. Hurley, Sr thanking him for his assistance.

This is great. Thanks for sharing.

I’m curious if the original of the letter your are quoting is in the North Carolina Room at Pack Library. How much of her letter is quoted in the Mizener biography?

I’m not sure how much of it is quoted by Mizener. Nor am I positive the letter in the North Carolina Room is the original. It certainly looks and feels like an original, typed on onion skin.

The swimming pool at Beaver Lake was not in the middle, but down at the far end; the remains of the retaining wall separating the pool from the larger lake can still be seen via Glen Falls Road. The middle of Beaver Lake would have been hundreds of feet from either shore, and so not easily reachable by most swimmers. The pool was demolished in the 1950s. https://packlibraryncroom.wordpress.com/2014/06/28/all-city-pools-now-open-except-the-one-at-beaver-lake/