Our series “Look Homeward” returns for its first 2024 installment. As readers may recall, this recurring feature explores the life, work and impact of Asheville author Thomas Wolfe on our area’s local writers, educators, historians and creatives.

Previous articles have included conversations with author Wiley Cash, musician and writer Alex McWalters, and Kayla Seay, site manager at the Thomas Wolfe Memorial.

In this month’s column, we speak with Katherine Cutshall, manager of the Buncombe County Special Collections, located in the basement of downtown Asheville’s Pack Memorial Library.

On Tuesday, Feb. 13, at 5:30 p.m., the library will host “Exile From Altamont? Race and Belonging in Thomas Wolfe’s Asheville, Part 1.” The series will continue Saturday, Feb. 17, at 2:30 p.m. Both events take place in Lord Auditorium at Pack Memorial Library, 67 Haywood St. Presenters will include Andrea Clark, Darin Waters, Kevin Young and previous “Look Homeward” participant Terry Roberts.

Xpress: Could we begin with your favorite Thomas Wolfe line and why it resonates with you?

“Fiction is not fact, but fiction is fact selected and understood, fiction is fact rearranged and charged with a purpose.”

Admittedly, I have never been able to make it very far in Wolfe’s most famous work, Look Homeward, Angel. It isn’t for lack of trying, I’ve attempted it several times. However, I felt compelled to read something by Wolfe, which is how I discovered his play Welcome to Our City. I fell in love.

This play [written by Wolfe in the early 1920s while studying at Harvard] is the first time he explicitly wrote about Altamont — the fictional town inspired by Asheville. … Hoping to learn more about Wolfe’s motivations for writing the play, I read the preface to Look Homeward, Angel and I came across the above quote that summed up the heart of Wolfe’s intent for his stories set in Altamont. This fictionalized Asheville provided him with seemingly endless opportunities to offer up his perspective, and criticism, of the culture and politics of his time. This line makes it clear that Wolfe saw his fiction as a catalyst for discussion of real-world issues.

Fill readers in on Welcome to Our City. What issues does the play specifically address and what about it spoke to you?

Welcome to Our City immediately grabbed my attention because I felt like I was reading yesterday’s news, only this play is 100 years old. At the time, I was in graduate school and thinking and writing a lot about tourism and its impact on Asheville throughout its history.

Set in 1923, the play chronicles the plot of a group of wealthy real estate investors who conspire to “do away with” the historically Black business and residential district of the town. The investors hope to secure cheap property for developing a white hotel and residential neighborhood under the banner of “Altamont: Bigger, Better, Brighter!” The main conflict arises when an affluent Black doctor leads a resistance and a riot ensues.

Throughout Welcome to Our City, Wolfe explores the intersections of race, class and gender while grappling with other sociopolitical themes of the New South. Though none of the events described in the play happened exactly the way Wolfe portrayed them, they are a rearrangement and exaggeration of fact.

Would you mind offering readers an overview of how the tourism industry evolved in Asheville within Wolfe’s lifetime: 1900-38?

Tourism, or something that looks a lot like it, has been a part of Buncombe County’s economy since some of the earliest days of colonial settlement. Folks from across the Southeast visited the area seeking respite from the intense heat and mosquito-borne diseases of the low country. In the early years, travel was rather difficult, but the introduction of passenger rail service to Asheville in 1880 kicked the industry into high gear.

During Wolfe’s early life, tens of thousands of visitors flocked to Asheville every year, and the city’s population soared. Given that his mother operated a boardinghouse, young Tom was in the thick of it. This influx of people and cash had a major impact on the development of the city. Asheville quickly became denser and more cosmopolitan — telephone service, electric streetcars and other modern amenities were available to travelers. People from across the country began investing in real estate at unsustainable rates. This era of prosperity couldn’t last forever, and by the time the Great Depression swept the nation, Asheville’s bubble had already burst.

As a historian, which of the many buildings that stood in Wolfe’s time, but have since been razed, would you have loved to explore and why?

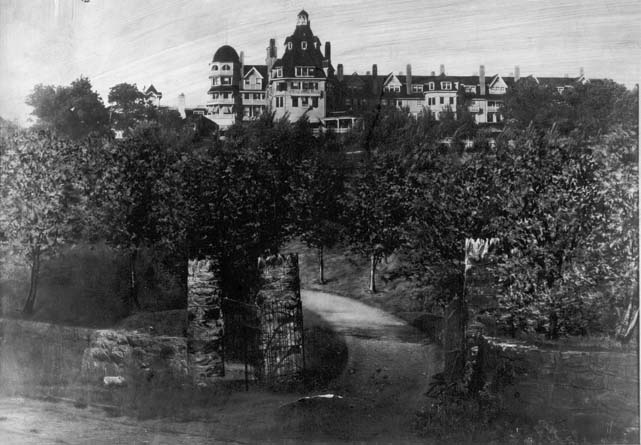

The “old” Battery Park Hotel. It was such an iconic feature of Asheville’s skyline for so long, and I have a hard time wrapping my head around just how different the landscape would have been before the the hill was razed.

Help new residents, or readers unfamiliar with it, understand the enormity of that former site and just how drastically different Asheville would look today had the land itself remained.

The Battery Park we see today was totally different than what was on the site when Thomas Wolfe was a child. Rather than the Spanish Revival-style building, the original hotel was a massive Queen Anne-style structure situated on the top of a large hill. The peak of the hill was about as high as the present hotel. Thousands of tons of earth were moved to create the plateau we know today and to fill in Coxe Avenue so that the road slopes rather than its previous steep drop-off.

During Wolfe’s time, Battery Hill rose far above the city and had a greater presence than the current hill and hotel. In Look Homeward Angel, Wolfe complained about the “new” Battery Park Hotel and other modern hotels going up all over Altamont, saying it was “stamped out of the same mold, as if by some gigantic biscuit-cutter of hotels that had produced a thousand others like it all over the country.”

As a historian, if you could meet with Wolfe and ask him one question about his time growing up in Asheville, what would you be dying to ask?

First, I’d want him to spend a week in 2024 Asheville. Then I’d like to hear his reflections on that week. I’m so curious to know his thoughts on 100 years of “progress.”

Do you think any of the city’s progress would surprise him?

It depends on what you mean by progress. In Welcome to Our City, “progress” — that is, to achieve “Altamont: Bigger, Better, Brighter!” — is framed as a farce and a cover for undermining working-class folks and other marginalized groups. I think he would probably roll his eyes and give a chuckle at exactly how little has changed.

Tuberculosis patients were a big part of the boom in the growths of tourists and residents in the early 1900’s .. The climate was said to be beneficial .. As a person who grew up in Asheville in the 50’s with both childhood asthma and a bad mold allergy I could never grasp how that could be. We spent a month every two years in the hot, high, and dry desert of Midland TX which I found to be FAR more hospitable to my ability to breath than the humid, cooler Asheville air. Ironically TB is what killed Wolfe (who was my grandfathers 1st cousin) at age 38.