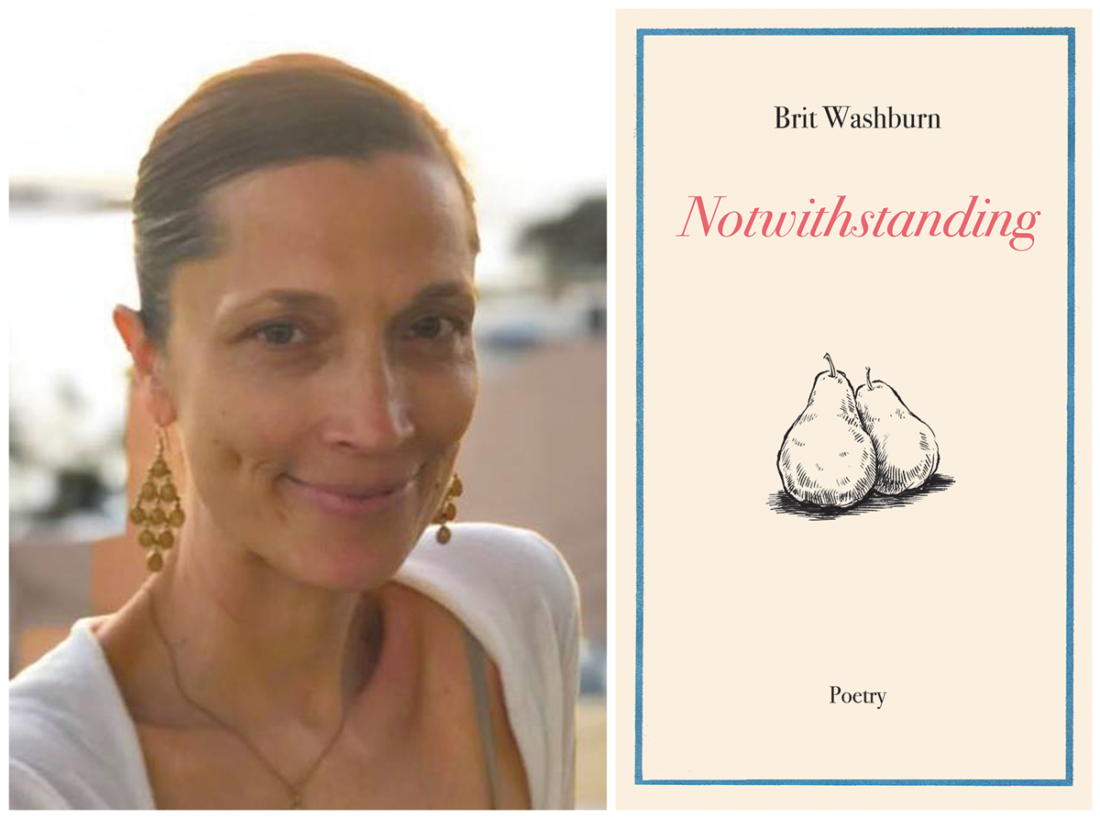

Local poet Brit Washburn doesn’t associate poetry with writing.

“It has, for as long as it has appealed to me, seemed a thing apart — the byproduct of a way of being in the world,” says the award-winning poet and author of the 2019 collection Notwithstanding. “To be a poet, to my mind, is to be aware. … To pay attention; to be curious and alert; to be receptive and reflective, reverent and irreverent, romantic and skeptical; to mourn and to praise; to contemplate, celebrate and salvage what we can of the universe, on behalf of our species. To be a poet, then, is no more or less than to be fully human and to translate and distill that experience into language so meticulously as to evoke and redeem something of life itself.”

Originally from northern Michigan, Washburn is a graduate of the Creative Writing Program at Interlochen Arts Academy and Goddard College in Vermont. She’s lived and studied in multiple states and countries, including New York, Hawaii, South Carolina, Brazil, France and Italy, before relocating to Asheville in 2017.

“The natural world and changes of season have always strongly informed my life and work, and moving to Western North Carolina has felt, in some respects, like a homecoming for me after so many years in tropical and subtropical settings which, however beautiful, always felt foreign,” she says.

Xpress recently spoke with Washburn about the importance of specificity within poetry, forms of inspiration and the ways a poem can help readers feel less alone. Along with the conversation is her poem, “November 11.”

November 11

Once a week or so, when we’ve dropped

her brother at the gym, and if there are

no pressing errands to be run, I take

my daughter on a date—a flight

of kombucha at Rosetta’s kitchen;

sushi at a sidewalk café, doughnuts

at Vortex or, her favorite, avocado

toast at the City Bakery.A window seat if one’s available.

Coffee for me, bubbly water

for her, and no one and nothing

to compete for our attention.I try not to look at my phone, try

to answer her questions

such as today’s about alfalfa

sprouts and Veteran’s Day,

the things that remain

mysteries to six year-olds—And to me, hard pressed as I am

to explain war, or why

her grandfather would never want

to be thanked for his service

in Vietnam, how often we don’t

know what we’re getting into

until it’s too late, then find ourselves

having done something

we can’t undo, and hate.All the while, she keeps

taking bites, her eyes wide

and glistening, as his must have been,

then, before I knew him,

the tangle of tiny shoots

the Arabs called the father

of all foods

curled into a small nest

on the side of her plate.

Xpress: Can you speak to the inspiration behind this poem?

Brit Washburn: As with most of what I write, this poem arose when I paused for a moment to notice. Multitasking, however necessary, is really hard for me, and it’s only when I’m doing one thing at a time that the impulse to write asserts itself. This happens most often when I’m reading or walking or sitting down with a cup of tea. In the case of this poem, it was while having coffee and avocado toast at City Bakery on Charlotte Street with my little girl. I noticed where I was and who I was with and why and what the sensory experience was like. Paying attention in this way almost always elicits an emotional response from me and frequently a tenderness toward the world around me. It has never seemed to me a mere coincidence that attention and tenderness share a root.

How do you think about the inclusion of proper business names and public locations within your work, especially as it relates to nonlocal readers.

All of us inhabit a highly specific world: We go to particular grocery stores and walk down specific streets, and the woods are full of certain species — even if those are different stores and streets and species for each of us. It makes sense to me then to learn and call these places and things by name, as a way of honoring their individuality. It also helps to ground writing in what is real and tangible, to avoid abstraction, which can be fatal. That said, most of what I write is set at home, or out in the natural world, so I would say “November 11” is a relatively rare instance of businesses being cited in my work, probably thanks to Frank O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died.”

Could you elaborate on the notion that abstraction can be fatal?

I like the idea that “the hands do the work of the heart,” and I like to think that language does, too: that it can allow us to translate subjective experience — our thoughts and feelings and impressions — into concrete imagery — sounds and sights and scents and tastes and textures that can be offered up to the reader, the other, extended like a branch or a hand. Abstraction does the opposite. Etymologically, it is a drawing away. The hand it extends is empty or nonexistent. It has no weight behind it, provides nothing to bite into, hold onto. An apple can be grasped, devoured. We can feel it fill our stomachs, crave it in its absence. So, I guess when I say abstraction can be fatal, I mean words devoid of substance offer little sustenance. Poems composed of abstractions are likely to fall flat, leave us feeling confused or cold or, worst of all, nothing. But throw in some bread and a wool blanket, and we begin to feel less alone in the world. If I would have poems do one thing, that would be it.

What was the revision process like for this poem in particular and your poetry in general?

Revision, for me, begins almost as soon as I put pen to paper, if not before then, in my head. I might write a few words and then shuffle them around before going further. Or sometimes a poem will be born close to whole, but I’ll immediately circle back to the beginning and start fiddling. As a result, I almost never have multiple “drafts.” My poems are much more like what we’re told of the human body: continuously shedding cells and generating new ones, so that every seven years, we’re an entirely different organism, but the process has been imperceptible. Similarly, I think I’m always making innumerable choices about form and structure when I write, but I rarely make big, conscious changes. The poems just evolve, as though they themselves are trying to find their way.

Within this poem, you’re capturing a moment with your daughter and a memory of your father. What was the process like in merging those two experiences within the poem itself?

My mother talks a lot about the symmetry of aging: how growing old is much like growing up, but in reverse. There is a way in which the wonder we see in the eyes of children mirrors the hard-won wisdom and wistfulness in the eyes of the elderly. Perhaps this was in the back of my mind when I wrote of them together. The juxtaposition of contrasts often seems to throw their relative significance into relief — war and alfalfa sprouts, for example — though in the case of my father and daughter, there’s nothing relative about it — neither could be more significant to me.

Is there a local poet whose new collection has you particularly excited and why?

I’m excited to see a collection from the Candler-based poet Mackenzie Kozak, though it has yet to come out. If confined to already published books, Nickole Brown‘s bestiary, To Those Who Were Our First Gods, is a feat in service of literature’s highest purpose: the cultivation of compassion. And Swannanoa-based poet Maggie Anderson‘s Dear All is among the most devastating books I’ve read in the past decade.

Lastly, who are the four poets on your Mount Rushmore?

My first thought would be just to let the mountain be a poem unto itself or stand for the great mountain poets Hanshan and Gary Snyder. But if we’re talking about American poets who have been important to me, I’d say Richard Hugo, Jim Harrison, Jane Kenyon and Louise Glück would be right up there.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.