Local poet Luke Hankins isn’t short of literary credentials and publications.

While in graduate school at Indiana University, he held the Yusef Komunyakaa Fellowship in Poetry. And his work has twice been shortlisted for the Montreal International Poetry Prize. But in the end, the poet says, “the only accomplishment any writer should worry about … is remaining devoted to the craft and calling of writing.”

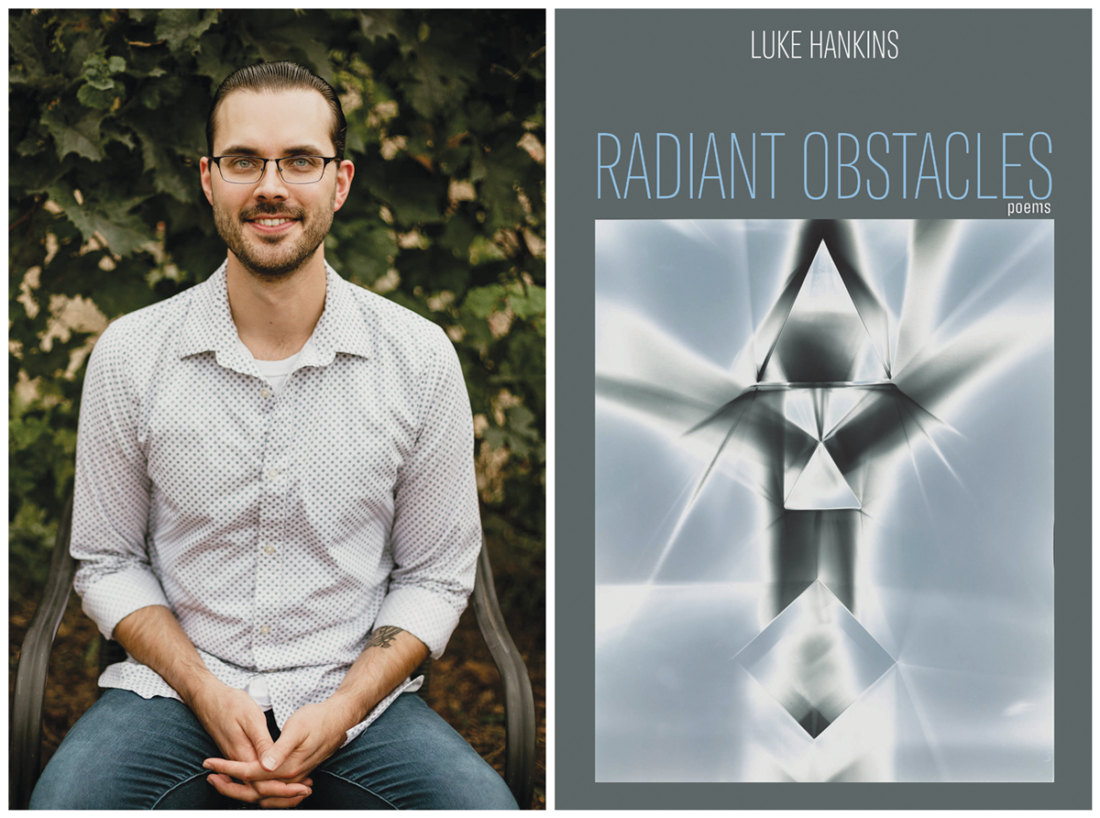

The founder of Orison Books, a local nonprofit literary press, Hankins is also the author of two poetry collections and the 2016 collection of essays, The Work of Creation: Selected Prose. His latest book of poems, Radiant Obstacles, came out in 2020.

Xpress recently spoke with Hankins about his writings, the power of metaphor and his interest in spiritual dilemmas. Along with the chat is his poem, “Even the River,” featured in Radiant Obstacles.

Even the River

In a constant murmur of leaves and branches

the mountains have been speaking to me

about how you left them, cardinals

flashing in and out of branches

signaling in red semaphore their grief

at your departure. All of nature

seems to address and blame me.

I walk around holding out my hands,

palms upturned, in a gesture

of bewilderment and surrender,

suggesting my innocence

but also my willingness to hold

the guilt that finds no other place to rest.

I go out at midnight to comfort the river

near the tracks where the trains pass

in a slow, unrelenting fury all night,

the spark of metal on metal

winding through the dark,

blaring their enormous questions

that I don’t know how to answer.

And even the river resists my touch,

like a small child who continues

to feel slighted

no matter how long

her father sits by her bed

stroking her hair and singing.

Xpress: Take us to the start — what inspired this poem?

Hankins: Like many of my poems, this one was inspired by a real-life event, a circumstantial separation from someone I cared about, but it became highly fictionalized. The actual event had nothing to do with guilt on anyone’s part, but the feeling of loss led me to imagine a character experiencing loss for which he did feel guilt and the way that sense of loss and guilt might overwhelm him to the point that he felt that the natural world around him was also grieving and accusing him of driving the person away. On one level, the poem is an exercise in an intentional “pathetic fallacy” — the projection of human feelings onto the nonhuman world. It’s not meant to reflect a material, objective truth, but a psychological one.

Let’s jump to the ending. Can you speak to the poem’s final image, which pulls readers away from the natural world?

That, to me, is part of the magic of metaphor — things can simultaneously be one thing and a quite different thing. The speaker doesn’t literally move inside, is still at the river, but through metaphor, a completely different scene is overlaid or, better, intertwined with the literal scene. Together, they become (I hope) more than either could be in isolation.

For readers less familiar with your work, what are some recurring themes and topics that you find yourself returning to as a poet, and what attracts you to them?

My poems tend to engage philosophical or spiritual dilemmas, often using the natural world as an occasion or a vehicle for the meditations. “Even the River” is actually sort of an outlier for me, though it does appear in a section of Radiant Obstacles focused on human interconnection and relationships more than is typical for me, and the poems in the section are on the more narrative side of the spectrum. So, I do have at least some range, I suppose!

How do you hope your poetry impacts readers?

I think that everyone who writes or makes art or music tries to make something that’s true to their own experience of what it means to be human. So, I don’t set out to offer something that I think is outside the bourn of others’ experiences. There’s the old saying — overused, but still useful, I think — “The particular is the universal.”

I have faith that delving into my own experience of the world will resonate with others because humans share so much in common despite all the superficial differences. The reason I fell in love with poetry as a teenager, in fact, was for that very reason — reading something written in a very different place and time, but which struck me as a profound expression of something I recognized, something I, too, had felt or thought. As John Keats wrote, poetry “should strike the reader as a wording of [their] own highest thoughts and appear almost a remembrance.”

That being said, not all poems will speak to all people in the same way or to the same degree. So, it’s a good thing there are so many poets. We can each find the work that speaks most deeply to us.

Is there a collection from a local poet that excites you and why?

Eric Tran just moved away from Asheville — but for the purpose of this question, I’m going to consider him a local. His second poetry collection, Mouth, Sugar, and Smoke, was recently released by Diode Editions. These powerful poems delve into grief over a former lover’s substance dependence and also celebrate queer eros.

Lastly, who are the four poets on your Mount Rushmore?

Can I cheat? I’m going to cheat. Dead poets: George Herbert, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Dickinson, Rainer Maria Rilke. Living poets: Jane Hirshfield, Jericho Brown, Christian Wiman, Li-Young Lee.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.