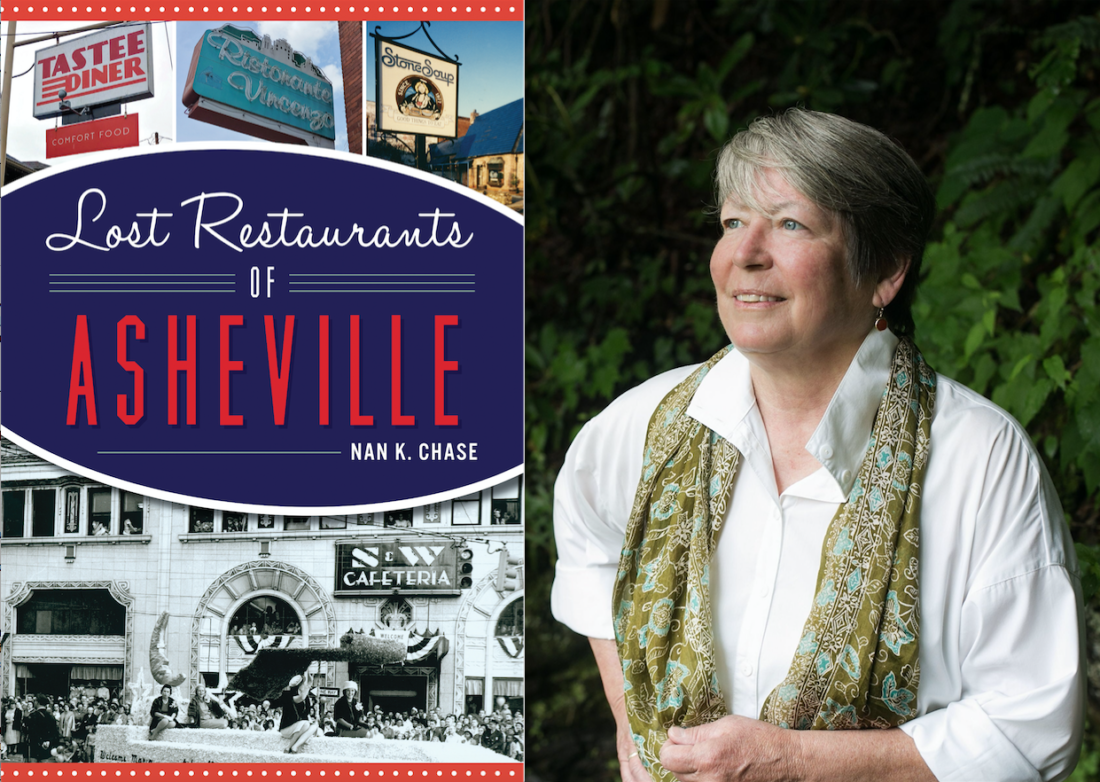

Don’t let the title of Nan Chase’s latest book — Lost Restaurants of Asheville — fool you. Yes, eateries of yesteryear fill its pages, but the work is far from a simple, nostalgic look back at the city’s former drive-ins, lunch counters and burger joints.

“It’s not a smiley-face history,” says the author — a fact she shared with the book’s publisher, The History Press, before taking on the project.

Along with old recipes, classified ads and photographs from bygone eras, the book’s chapters examine immigration, segregation and gentrification. Her goal for writing the book, notes Chase, was to tell the city’s true story.

On Wednesday, Dec. 18, the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library will celebrate its release with a launch party. Chase will speak at the event as well as hold a book signing.

Images of the past

By Chase’s estimate, thousands of restaurants have come and gone since Asheville’s incorporation in 1797. The 32 featured establishments in her book, however, operated primarily in the 20th century. As part of The History Press’ Lost Restaurants series, available photography played a determining factor, Chase explains.

Many of the featured images show the interior layout of former restaurants like the Red Carpet Room at Bucks on Tunnel Road, the Biltmore Plaza Recreation Center and the original S&W Cafeteria. Others capture unique signage, advertisements and menu designs. Shots of more recent establishments like Stone Soup and Laurey’s Gourmet Comfort Food are also featured.

And then there are a handful of gems like the Silver Dollar Cafe. Originally located on Roberts Street, the entire building was loaded onto a truck bed and moved to Clingman Avenue in the early 1970s — the chapter’s featured image shows the small building headed to its new site. Operational from 1934 to 2011, the former cafe is now home to All Souls Pizza.

Of course, not all of the book’s photography is as whimsical. For example, a pair of holiday photographs, circa 1950, reflects Asheville’s then strict adherence to segregation laws. Both photos were taken at Tingles Cafe, which operated from 1918-73.

In the first image, the restaurant’s white staff poses before a Christmas tree alongside owner Alvis Tingle; half the group is seated at a table (adorned with white linen and holiday décor), while the other half stands. The second photo shows the cafe’s black staff gathered around the same Christmas tree; the women are lined up in a single row while the male chefs crouch in the empty space previously occupied by the table.

Mudholes and volcanos

Though photography may have played a part in shaping the book’s focus, Chase’s research and language are what bring the stories to life. In one example, the author’s vivid descriptions transport readers back to the start of the 20th century. “Greek immigrants had begun settling around Asheville soon after 1900, when much of the downtown was still a ‘mud hole’ with only rudimentary public services,” Chase writes. “Sidewalks were wooden planks laid over knee-deep mire. But demand for food was high, and working in cafes and restaurants quickly became a favored career.”

A few chapters later, readers are in post-World War II Asheville, when a series of drive-ins on Tunnel Road were all the rage. The drive-in restaurant model itself is emblematic of the period’s popular portrayal as a time of innocence and prosperity, when carefree teenagers cruised the streets, grabbing burgers and milkshakes on Friday nights.

Rather than perpetuate this narrative, Chase reminds readers of the social and political unrest that simmered beneath the surface. “In the first exhilarating postwar years, it would be nearly impossible to see [the social] changes ahead, the cracks in the foundation, the seismic shifts between the races and the sexes that would fracture the cultural landscape,” she writes. “It was as though Americans were about to build an amusement park on a volcano.”

Later, as the country grappled with civil rights and protested the Vietnam War, Asheville’s downtown fell into a death spiral. Businesses and restaurants alike fled the district for the latest craze: the indoor shopping mall. Of course, the mass exodus is what ultimately made it possible for the next wave of culinary visionaries, who in the late ’70s and ’80s took advantage of the cheap rent in the city’s seedy downtown, paving the way for today’s nationally recognized, award-winning restaurants and chefs.

“There would not have been a twenty-first-century rebirth of downtown Asheville if first it hadn’t died,” Chase writes. “That dying took only fifteen years, but the misery lasted far longer.”

A toast to the industry

The book’s inclusion of social history lends weight to a topic that might have otherwise been forgettable. With it, Chase offers an interwoven and complex tale that is both unique to Asheville and reflective of the country at large.

But along with an honest look back, Lost Restaurants of Asheville is also a celebration of the city’s culinary scene and the sense of community each former establishment created. Through this lens, the book reads as an extended toast to the entrepreneurial spirit and work ethic of Asheville’s bakers, bartenders, owners and chefs — past and present.

WHAT: Lost Restaurants of Asheville launch party

WHERE: Lord Auditorium at Pack Memorial Library, 67 Haywood St. avl.mx/6eu

WHEN: Wednesday, Dec. 18, 6-7 p.m. Free

Great overview of what looks to be a great book. What “lost restaurants” do your readers remember? What was the name of the Chinese restaurant on Broadway St in the early 1970s? The restaurant at the top of the Battery Park Hotel? Does Schandler’s Pickle Barrel count as a “lost restaurant?”

The. Chinese place was Paradise Restaurant…see that chapter. Schandler’s reappears as a location of Stone Soup, I think, today’s Mellow Mushroom. There are lots of amusing stories, including a lobster rescue.