As long as even one child lacks access to health care, Kim Elliott believes she needs to advocate for that child. The way she sees it, it’s part of her job, both as superintendent of the Jackson County Public Schools and as a caring human being.

So when Tammy Greenwell, chief operating officer of Blue Ridge Health, suggested that they sit down to talk about an in-school clinic, Elliott eagerly agreed.

“It made sense to go down this road,” says Elliott, who was already familiar with the organization’s school-based clinics in Henderson County. “Thanks to Blue Ridge Health, we already have better access to care than a lot of other rural districts, but we still have people who need better access.”

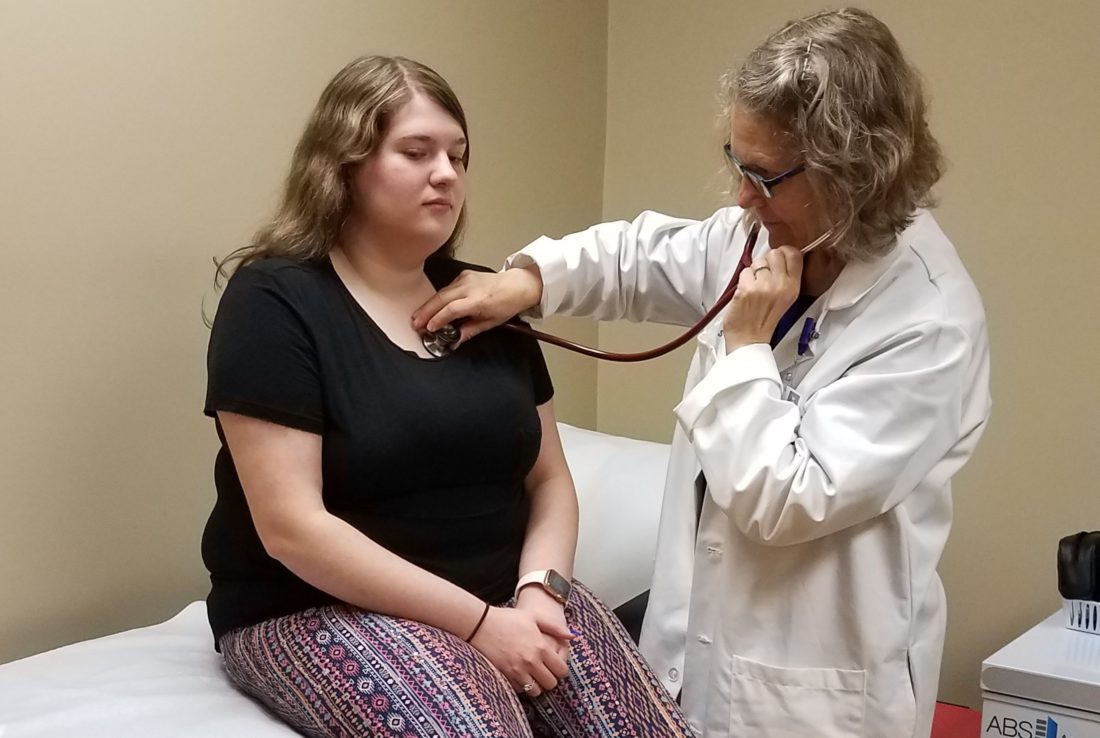

School-based health clinics bring needed preventive and acute care, health education and other services to students. The programs vary from district to district because each community designs its own program, says Lee Homan, Blue Ridge Health’s director of marketing and communications.

So far, the nonprofit has opened eight school-based clinics: five in Henderson County, where the child poverty rate is 22.5% and 5% of children have no health insurance; one in neighboring Polk County (21.3% child poverty, 5.8% uninsured children); and, last month, two in Jackson County. Those numbers are from The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s 2018 Kids Count report.

These clinics offer basic care and accept all forms of insurance. For people who are uninsured or who have a high-deductible policy, there’s a sliding scale based on income and household size, and if a higher level of care is needed, those patients can be seen at one of Blue Ridge Health’s primary clinics.

“We do not turn anyone away on the basis of inability to pay,” stresses Greenwell, adding, “This care is accessible.”

Even uninsured patients who subsequently obtain insurance can continue to see the Blue Ridge Health physicians. That’s often not the case at free clinics, which may not have the capacity to continue seeing people once they have other options.

The two new Jackson County clinics are in Fairview School (K-8) and Smoky Mountain High School. Elliott says she hopes to see expanded hours at both clinics and to open additional clinics in the future.

“Every child — everyone — should have access to health care,” she declares.

High-deductible plans on the rise

Nationwide, about 2,000 school-based clinics serve more than 2 million students, primarily in areas with a shortage of health care providers, notes Homan.

All the schools in the Jackson County system are designated Title I, meaning they receive supplemental federal funds because they have a large percentage of low-income families, Elliott explains.

In Jackson County, the child poverty rate is 22.5%, according to the Kids Count report. It also found that 6.6% of children in the county are uninsured. In all these counties, the figures don’t include insured children whose family policy has a deductible of $1,000 or more.

Although many low-income children in North Carolina are covered by NC Health Choice, some still fall through the cracks, says Greenwell. In addition, growing numbers of children whose parents have high-deductible insurance plans are still left with no effective access to care since, under IRS rules, those policies may require people to pay as much as $6,650 before benefits kick in.

In 2018, 47% of health insurance policies for people under 65 were high-deductible plans, according to a National Center for Health Statistics survey. That’s up from 43.7% the year before.

For many working families, a high deductible renders their policy essentially unusable. Often, says Greenwell, families are forced to postpone getting care because they haven’t met their deductible and can’t afford to see the doctor. In effect, says Elliott, they have no insurance.

The challenges don’t end there, however. Many parents either can’t take time off from work to bring a child to the doctor or they have to take unpaid time off, which puts a further dent in the family finances, says Dr. Judy Seago, the pediatrician who oversees Blue Ridge Health’s school-based clinics.

“We see children with a wide range of problems: appendicitis, respiratory infections, flu. We saw whooping cough in Hendersonville last year,” Seago recalls. “A lot of these children can be seen and treated while their parents are at work, as long as they’re registered.”

To register, parents must provide a health history and give permission for their child to be treated.

Saving lives and dollars

In the long run, these clinics also save money, notes Elliott, since the cost of postponing treatment can be high.

“Children can have a respiratory infection develop into pneumonia,” she points out. “Asthma can get much, much worse. Complications like these can be extremely dangerous for a child and much more expensive to treat.”

The solution, she says, is to manage chronic illnesses and treat minor infections before they become life-threatening.

Startup funding for the Jackson County clinics came from the Great Smokies Health Foundation, which provided $5,000, and the Foundation for a Healthy Carolina, which gave $25,000. The money was used to purchase medical and computer equipment, furniture and supplies.

“Children learn best when they are well,” says Elliott. “If we can help them be well, they’ll have a better chance at a good life — better health, a better learning experience, a better job.”

According to a 2018 report by the American Public Health Association, students who use school-based clinics have better grade-point averages and attendance records than their peers who lack access to such facilities. School-based health centers “have tremendous potential to improve the health and well-being of the entire student population,” the report states.

Other benefits, it notes, include:

- Higher grade promotion.

- Reduced suspension rates.

- Reduced noncompletion rates.

- Increased use of vaccination and preventive services.

- Fewer emergency department visits and hospital admissions.

- Higher contraceptive use among females.

- Improved prenatal care and higher birth weights.

- Lower illegal substance use and alcohol consumption.

- Reduced violence.

“It’s pretty much a win for everyone,” says Elliott.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.