Robert Goettling and his wife are “amateur people trying to live a little bit green.” In their former home in Chicago, they installed 36 solar panels on their roof to run the home off-grid, selling the remaining energy back to the electric company.

When the couple decided to leave the city and move to Asheville, they looked for a private homestead where they could “get more into the whole sustainable, green thing,” Goettling says. An opportunity soon presented itself in Woodfin — a discounted price on a lone home on a mountainside, the only standing residential structure in a 400-acre defaulted development.

“There was no one else up here,” Goetting says. “When the bank took the development over, this was the only house that was even under construction.”

But within a month after the Goettlings moved in, that begin to change. “All of a sudden we started to notice there were guys mowing and taking care of the roads,” Goettling recalls. “Then we started seeing lights on in the sales office.”

The bank had hired a local company to salvage the project. The property was soon split between two development firms, and lots began to sell. Goettling says parcels that were priced at $700,000 in 2006 were being being offered at $90,000, including lots on ridge tops or mountainsides with steep slopes.

Dismayed by the new construction, Goettling and his wife began negotiations to purchase some of the undeveloped land. Initially, they hoped for 20 to 30 acres, but when the bank failed to find new investors, the couple were able to grab 165.

“We didn’t know when we bought it what we really wanted to do,” Goettling says. “But after we saw the development going on, we knew there was no way we could do anything but protect it. Because the rest of the mountain is going to be ruined.”

The pair began planning a conservation project temporarily called Ecostead Versant. Planned construction is minimal, limited to a barn, a greenhouse, irrigation ponds, an education center and small, dormitory-style housing where people could stay while studying sustainability principles.

Goettling and his wife are bankrolling the entire project, free from grants or financing that would “compromise their vision.” They’re partnering with local permaculturists, landscape architects, preservationists and engineers to “preserve everything forever,” Goettling says. It’s an ambitious project and not one they expect many of their new neighbors will be able to follow.

“Most people won’t be able to do what we’re doing, but the goal is to allow people to see what you can do,” Goettling explains. “And what better place to do that than a site where you can look around and see everything that has been done the wrong way and also see what it looks like when it’s done the right way.”

When the country becomes the city

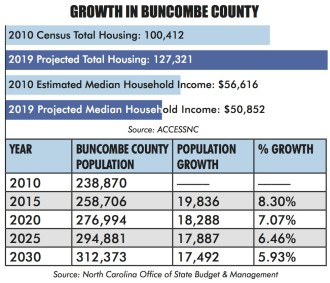

The Goettlings aren’t the only Buncombe County residents who have come face to face with rapid rural development. As more and more people move to the Asheville area, the need for housing is facilitating larger-scale development in traditionally small, isolated and rural communities. And how to approach that development sustainably isn’t always easy to figure out or agree upon.

Take the recent example of Coggins Farm. When the 169-acre historic farmstead off Riceville Road went on the market, many neighboring residents raised concerns of high-density development that would threaten their rural way of life. Those fears seemed poised to become a reality when developer Case Enterprises LLC (later called Coggins Farm LLC) submitted plans for a mixed-use development featuring a school, retail spaces and 382 residential units. Though some praised the proposed development for its inclusion of practices often labeled sustainable — clustered housing, walkability and open space for agriculture — others questioned the developers’ commitment to those ideas when confronted with a bottom line.

Meanwhile, another community group called Coggins Conservation Project pursued its own plans to purchase the property and began promoting a land-use principle called New Ruralism. According to CCP organizer Ron Ainspan, the group’s hope was to maintain the property primarily as a place for agriculture and as a public resource.

“One of the basic notions of New Ruralism is that it designates and protects agriculture lands in rural areas on the outskirts of urban areas as a way to help the vitality of both the city and the countryside,” Ainspan explains. “The New Urbanist approach creates walkable cities with more traditional neighborhoods and encourages cities to be self-contained and sustainable. New Ruralism reflects that in a way because it protects the characteristics of the traditional rural communities that surround the city while supporting urban areas through fostering the local food systems.”

Ultimately, CPP’s plan for the Coggins site was not successful. Coggins Farm LLC finalized its purchase of the property in June with a revised plan that some in Riceville would likely consider a victory. The final plan calls for 99 residential units, removes many additional construction elements (including the school and the commercial areas), and the developers say the design includes community gathering spots and trails that honor the history of the land.

But Ainspan says that proponents of New Ruralism see the transformation of historic, rural farmlands into private development as a loss since the land will not be accessible or useful to the public.

“Even if the development is ‘greener,’ unless that land is accessible, it doesn’t matter,” Ainspan says. “One important principle of New Ruralism is that these agricultural areas be accessible to all residents of the community. When you create a private development, even if it has one farm or a conservation area, you create a ‘country genteel’ and the land isn’t being used to promote what’s best for the greater rural area or the neighboring city.”

How we define sustainability

While it might seem that the term “sustainable” or theories like New Ruralism and New Urbanism are freshly coined buzz terms, urban planner David Nutter, owner of Nutter Associates, says the concepts behind these ideas aren’t exactly new.

Pointing to the ideas of landscape architect Fredrick Law Olsmtead, author Ebenezer Howard and planner Randall Arendt, Nutter says there’s a long tradition in community planning of examining the relationship between urban and rural spaces.

“We’ve been thinking about these things all along the way, though I don’t remember anyone calling it ‘sustainability’ 50 years ago,” he says. “But I believe town planning has always been dedicated to the idea of sustainability, even if we didn’t have the environmental science that we’ve developed in the meantime.”

According to Joan Walker, campaign coordinator at MountainTrue, one very essential point that’s made by New Ruralism proponents is the idea that urban and rural areas are ultimately linked.

“In the city, we often think of the county as the ‘out there,’” Walker says. “But the two are dependent on each other. In Asheville, we are defined by the land around us. Our water, our great local food, our resources, can be protected or wrecked in the county.”

Growth is inevitable, Walker says, so the question can no longer be, “How do we keep development out of rural areas?” Instead, she suggests finding a way to prioritize how we want development to proceed. The same piece of land can be developed in very different ways with different visual, ecological and cultural impacts, she adds. Housing can be clustered to reduce the disruption of natural vegetation, and land can be designated as preserved green space.

Of course, just because a developer bills a project as environmentally friendly or sustainable doesn’t make it so. “When you’re looking at a claim of something being ‘green,’ whether that’s a product or a building or a subdivision, you need to ask questions and look out beyond your personal boundaries — think about how it impacts other communities,” Walker says. “For example, you can say you have green space in a development, but if you have a field that you keep mowed and sprayed with pesticides, you might as well pave it because you’re pulling from water for irrigation, polluting the ground with chemicals and providing no vegetation for wildlife.”

So what does make a development sustainable? Nutter says ideal developments are mixed-use, combining residential, commercial and cultural opportunities, and combine the three elements of sustainability: healthy physical environments, social networks and an economic system that can continue itself.

“Interconnection is key,” he explains. “All these things have to mesh with each other. I think that’s the whole point of sustainability — it’s one system.”

Nutter says there are several questions you can ask when determining if your subdivision or community is sustainable: Is it walkable? Is it close to employment or commercial shopping opportunities and institutions like hospitals, schools or churches? How steep are the slopes, and is there a plan to handle water runoff and erosion? How is the water quality? Where is the well and the septic tank, and what condition are they in? Does the neighborhood have a diverse mix of people? Is it accessible to people from a variety of backgrounds? Where can children play? Is there green space, and is it continuous green space that connects to other properties and allows wildlife to roam?

These sorts of questions are being asked and addressed in progressive subdivisions throughout the United States, Nutter adds, pointing to examples such as Seaside in Fort Walton Beach, Fla., Chesire Village near Black Mountain and parts of Biltmore Park. But a greener subdivision also means residents need to be willing to forsake more destructive amenities, he adds, including heavy reliance on automobiles or the desire for sweeping mountain views — usually attained through deforestation.

Of course, in order to make homes in these subdivisions affordable, the developer also has to hit a price point. Maintaining all the sustainability principles that were present in the development’s design may be a challenge, Nutter says, especially as the cost of labor and materials rises. And with Asheville and Buncombe County seeing an influx of younger people with moderate incomes, there is not only a housing gap — meaning more people are moving here than the current housing stock can hold — but also a demand for affordable homes, even if those homes might be not as green as they were originally envisioned.

Planning for the future

While communities have rallied in opposition to projects like the Coggins Farm development (now called Sovereign Oaks) or the proposed 140-unit Maple Trace subdivision in Reems Creek, Walker says there hasn’t been much of a county-wide effort to define how we want development of rural areas to proceed.

“We need to look at, over time, what is going to be the aggregate impact of these decisions we’re making,” she says. “And I don’t think we can do that on a development-by-development basis.”

Nutter points out that other parts of the country have looked to smart growth principles —a planning theory that promotes keeping development within existing urban centers where services and infrastructure already exist.

“Normally, smart growth in the United states is facilitated if not insisted upon by the state government of that place,” Nutter says. “But we have to be realistic. We do not have that in North Carolina. In fact, we seem to have a growing state resistance to this sort of thing.”

Nutter adds that Asheville and Buncombe County have made several strides in planning, including the county’s density standards and designated use districts and the city’s accessory dwelling ordinance, which will increase the opportunity for affordable housing in existing lots. But he adds that large portions of truly rural Buncombe have open-use districts where there are few restrictions on what can be built. There can also be resistance in these areas to any increased zoning.

“There’s a culture and a way of life in many agricultural and very rural areas that tends to not want the kind of zoning that is like a city’s zoning,” Nutter says. “This is true all across the United States.”

Other states, such as Oregon, Maryland, Massachusetts and Delaware are stricter with their smart growth zoning, Nutter adds. Oregon has a growth line around cities like Portland where areas surrounding the city are preserved to protect agricultural land as well as undeveloped rural land such as mountainsides and steep slopes. But don’t expect to see those kinds of regulations in WNC anytime soon, he says.

“I’m not sure Buncombe County is ready yet for strong controls on the outside rural areas,” he explains. “People who live in those places love their land and also want to protect it, but they don’t want a lot of government control. This is a property rights state, and America in many ways was founded on property rights.”

Walker adds that ultimately neighbors will need to come together to decide what they want development in their communities to look like. She adds that tools such as form-based codes or zoning overlays can help communities to enforce additional restrictions on development, but ultimately it takes organizing — communicating with commissioners, going to planning board meetings and asking questions of planners — to see real results.

“Decision-makers or people who sit on the planning board don’t just dictate what’s going to happen,” Walker says. “They want to hear from communities. There are plenty of places — Sandy Mush, Reems Creek, Leicester — that are going to be seeing more development. The Coggins property is not the last large farm that’s going to be facing development issues.”

Thinking ahead

Walker notes that the influx of new people to the area means urban growth is going to continue spreading out into the rural areas on the city’s borders. “We need to recognize that a lot of people are going to come here, and that’s good because they have good things to contribute to our community,” she says. “But we have to figure out how we’re going to accommodate all these people in a way that is best for everyone. And that takes planning.”

Goettling adds that many new homeowners fall victim to what they don’t know by purchasing discounted lots that are too steep or will disrupt wildlife. “They see a great deal on a lot, and they buy it, and who can blame them for that?” he says. “I know that most people do not want to destroy the things that make this place so beautiful, and I know that they do not want to hurt their community.”

Ultimately, everyone is a “sustainability wannabe” with a lot left to learn, Goettling says. But he hopes his project will help others to think about the impact of their own development.

“If you buy 170 acres or you buy a small lot, you have to look at it as ‘You just bought the responsibility to take care of it and to think about what happens to it after you’re gone,’” he says. “If instead of thinking about having a cool house with a view, if you’re focusing on the responsibility of taking care of that particular piece of land and doing what’s right for that space, you get so much more enjoyment out of it and ultimately a better outcome for everyone around you too.”

You answered some questions about the Coggin’s Farm. I hear about it on NPR and wondered. “Safe place to wander.” What does that mean? Armed guards or patrol dogs? When I wander, the most I worry about is stepping into a hornet’s nest. People are such scaredy cats.

Carrie, I love reading your stuff.

Thanks Dona!

What’s the carbon footprint of these developments, both relative to urban areas and relative to “less attentive” development in the same area? That’s really the bottom line question for sustainability, isn’t it?