As cities across the country struggle to respond to clamorous calls for and against removing monuments and memorials with ties to the Confederacy, Asheville’s long-standing debate about what to do about the Vance Monument — and the nearby marker commemorating Robert E. Lee and Confederate Col. John Connally — has heated up again.

Complicating the issue in North Carolina is a 2015 statute that strictly limits what municipalities can do with the monuments that speckle courthouse lawns, universities and public squares across the state.

Amid discussions centered on the law, Asheville’s history and the monuments’ context, a more basic conundrum has emerged: Who owns Pack Square?

This seemingly straightforward question is clouded by a 116-year-old contract between northern philanthropist George W. Pack and Buncombe County for the small spit of land at the center of Asheville’s physical and cultural identity. Though city and county officials have been scrutinizing the legal ramifications of the deed, neither municipality’s legal department can provide a definitive opinion about which entity can claim ownership of the parcel where the monuments stand at this time.

Off the map

In our digital age, an extensive online property database and map available through the Register of Deeds website (avl.mx/435) generally yields answers to questions about land ownership. But while the majority of Pack Square — including the amphitheater, Roger McGuire Green and Splasheville — falls under the purview of the county or city, the small rectangular square at the terminus of Patton Avenue where the Vance Monument, Lee/Connally marker and adjacent fountain sit has no identifiable owner listed. In fact, there’s not even a plat for the property.

Often this kind of inconsistency can be solved with a quick call to the Register of Deeds office. But after several hours of searching through public records that span over a century, Register of Deeds Drew Reisinger has no clear answer either. “When you first asked if I could help you shed some light on who owns the land of Pack Square, I thought I would likely be able to email you a deed from George Pack to the City or County and that would be the end of it,” Reisinger says. “This piece of property, that has been subject to lawsuits, is a good example of why citizens are strongly encouraged to get the help of an attorney when transferring property. While most of us have a general understanding of how property is transferred in North Carolina, the laws surrounding [it] are complex.”

City officials seem equally perplexed. At City Council’s Aug. 22 meeting, Council member Julie Mayfield alluded to the mystery in her response to residents’ calls to take the monuments down. “They may seem like simple questions … but they are not simple from a legal standpoint,” Mayfield, an attorney, said. “We, of course, have to be very careful not to put the city into legal jeopardy.”

‘Pack’ in the day

How can such a high-profile parcel of land in the center of Asheville not be accounted for? The answer begins with the arrival of George Willis Pack in 1884.

Pack Square’s namesake was a New Jersey native who built his fortune through logging operations in Wisconsin and Michigan. Seeking the healing climate that made Western North Carolina a favorite destination of America’s elite in the late 19th century, and possibly scouting Southern timber reserves, Pack and his wife moved to WNC in 1884, according to retired UNCA Special Collections archivist and historian Helen Wykle, who produced an extensive history of Pack Square as part of the the park’s renovation in 2006.

Pack immersed himself in the city’s development, buying up land and becoming a leading figure in the civic affairs of the region. He was an early advocate of such modern-day amenities as electricity, streetlights, sidewalks and sewerage systems. Pack was also influential in forming the Swannanoa Hunt Club — which would evolve into the Grove Park Inn — establishing public schools in the city, and founding the public library, Mission Hospital and several parks around Asheville.

“He saw a growing metropolis in this small city of Asheville and an opportunity to help build a community he had chosen to be invested in,” Wykle says.

Asheville’s odd couple

Pack also befriended other members of Asheville’s aristocracy, including Zebulon Vance, then a serving North Carolina senator. The friendship was a strange pairing ideologically: Vance, while not a fire-breathing secessionist, had actively served in the Confederate rebellion as a military officer and governor of North Carolina, and used his postwar position as a U.S. senator to limit African-Americans’ civil and voting rights across the South.

By contrast, Pack was a staunch abolitionist and prominent supporter of Abraham Lincoln during the war. Pack worked closely with Beaumont Street School, the first public school for African-Americans in Asheville, going so far as to personally pay the salaries of two teachers.

What was the bond between the Yankee anti-slavery industrialist and North Carolina’s Confederate “War Governor”? Wykle points to Vance’s more magnanimous side, noting that the governor took pains to feed federal prisoners during the Civil War and was supportive of the Jewish community at a time when anti-Semitism was rampant throughout the country.

Another explanation for the close relationship between the two men could be the institution of Freemasonry, she notes. Vance was known to be a member of the Freemasons at the time, a social sphere Pack was also thought to inhabit.

Pack and Vance remained steadfast friends until the latter’s death in 1894, with Pack serving as a pallbearer at Vance’s funeral. In 1896, Pack approached Buncombe County officials with a grand idea to commemorate his departed friend, according to a 1916 Asheville Citizen article: “‘If the county of Buncombe will give the land in front of the courthouse for a site for a monument in honor of Senator Zebulon B. Vance, I will give $2,000 toward the erection of such monument.’”

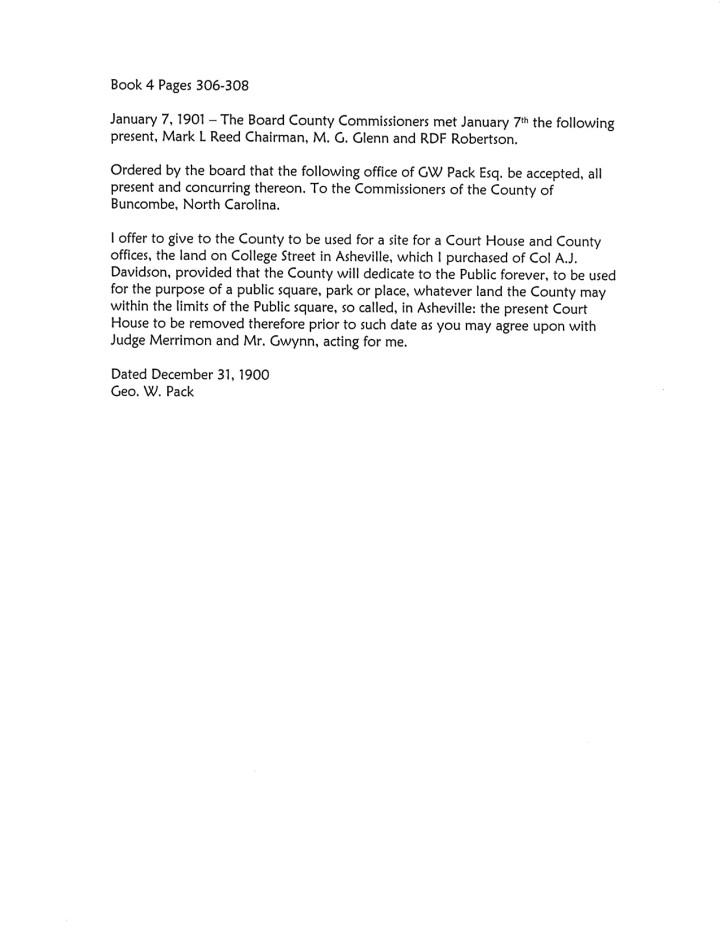

In addition to the personal donation, Pack was actively involved in the fundraising campaign for the additional $1,300 needed to complete the project. Buncombe County commissioners soon passed a resolution that “the land in front of the courthouse belonging to the County of Buncombe be forever dedicated to the use contemplated and referred to” in Pack’s proposition, and promised to furnish all deeds and papers to make it official.

Inauspicious start

The scene downtown on March 8, 1898, was one of joyous expectation, as Asheville residents gathered to witness the capping of the 65-foot Vance obelisk. As hundreds looked on, tragedy almost struck on that blustery day, according to an article in the Asheville Citizen from the time.

“[The] placing of the capstone was the most ticklish part of the work,” reported the Citizen. As the stone was hoisted into the air by a rope, the boom supporting it began to sway, and “there was a sound of cracking timbers that struck terror in those who watched,” sending the crowd into a wild rush, tumbling over each other.

Luckily, no one was hurt. The boom was rebuilt, the capstone set three days later, and the grand tribute to Vance was complete.

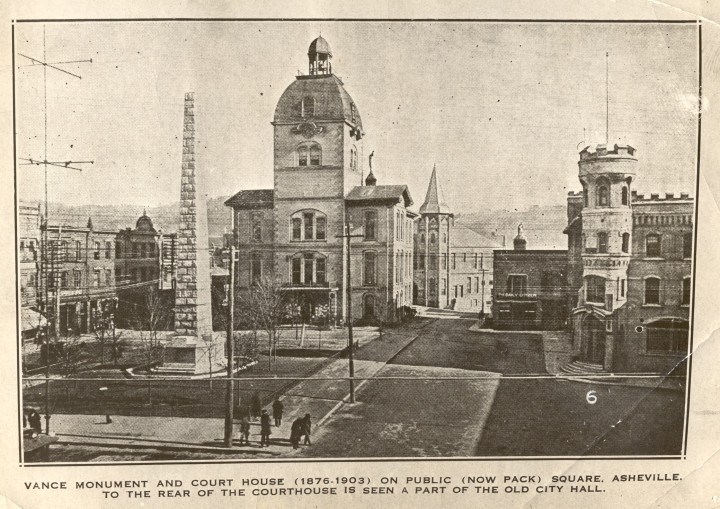

‘A public square so called’

Like many of the memorials erected across the South during the same era, the Vance Monument was placed in a prominent location. The Buncombe County Courthouse sat a couple hundred feet behind the site on what was then called Courthouse Square, overlooking the busy main thoroughfare of the growing city. While residents of the time may have marveled over their soaring new monument, the courthouse it fronted was less well-regarded. Historian A.F. Sondley described it as a “pretentious brick house,” and several historical accounts note its poor condition by the turn of the century.

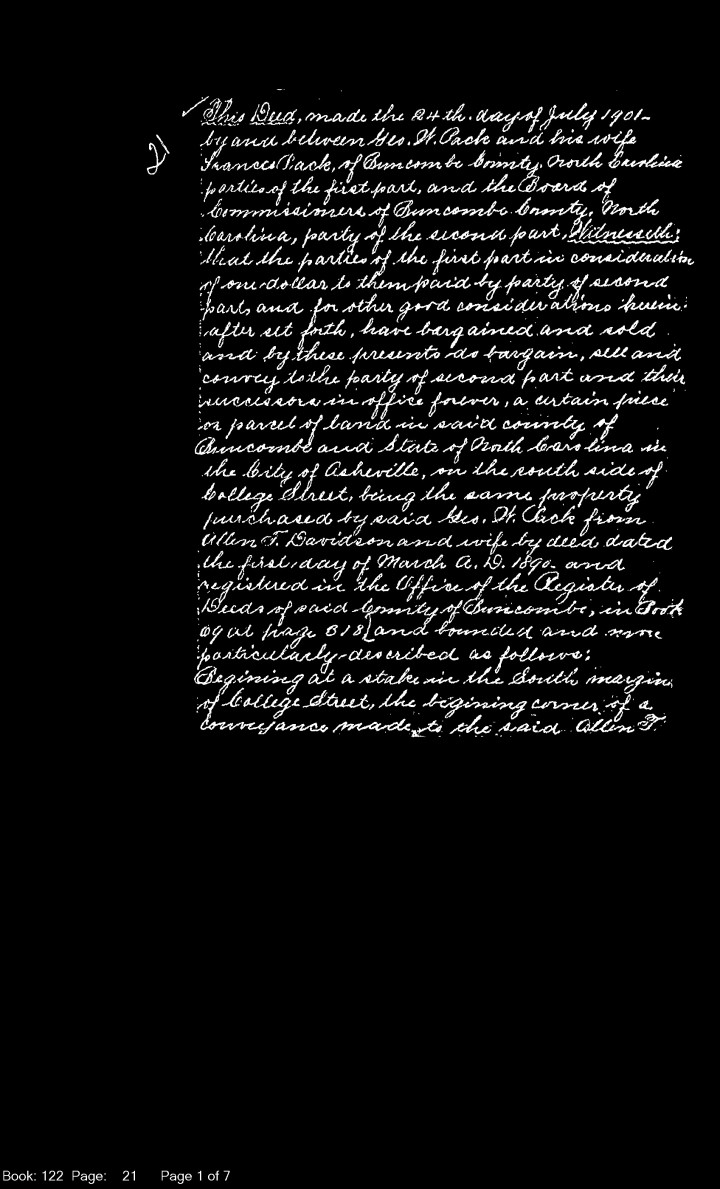

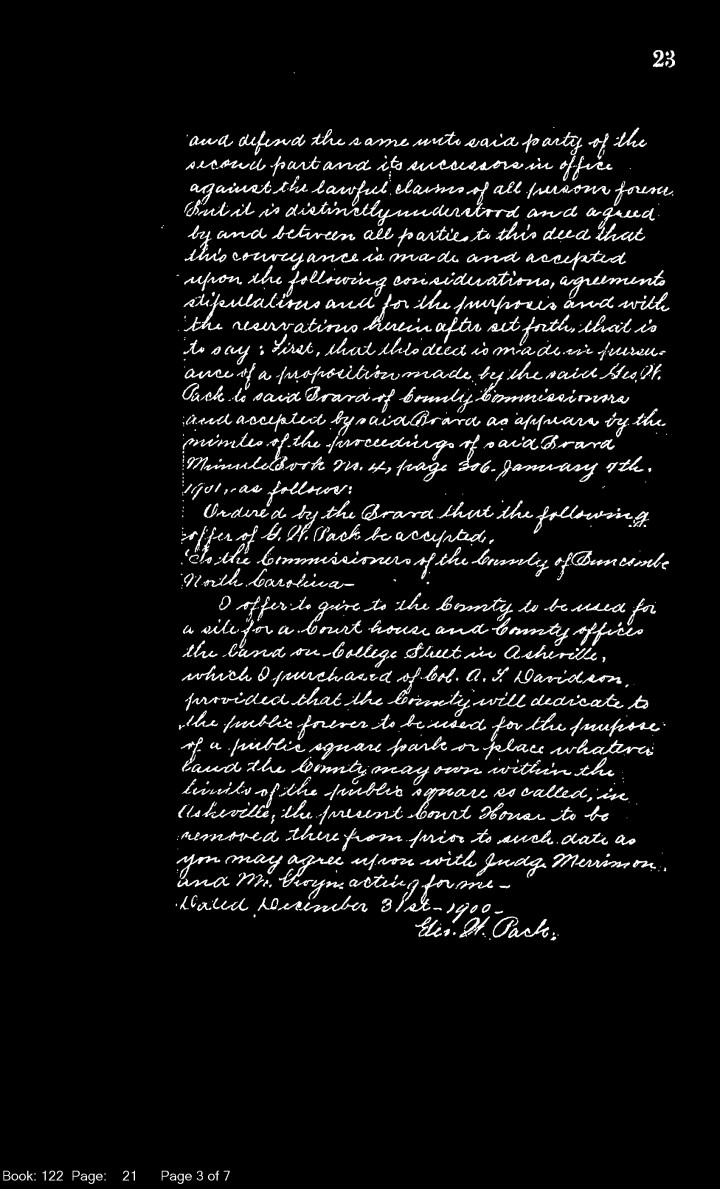

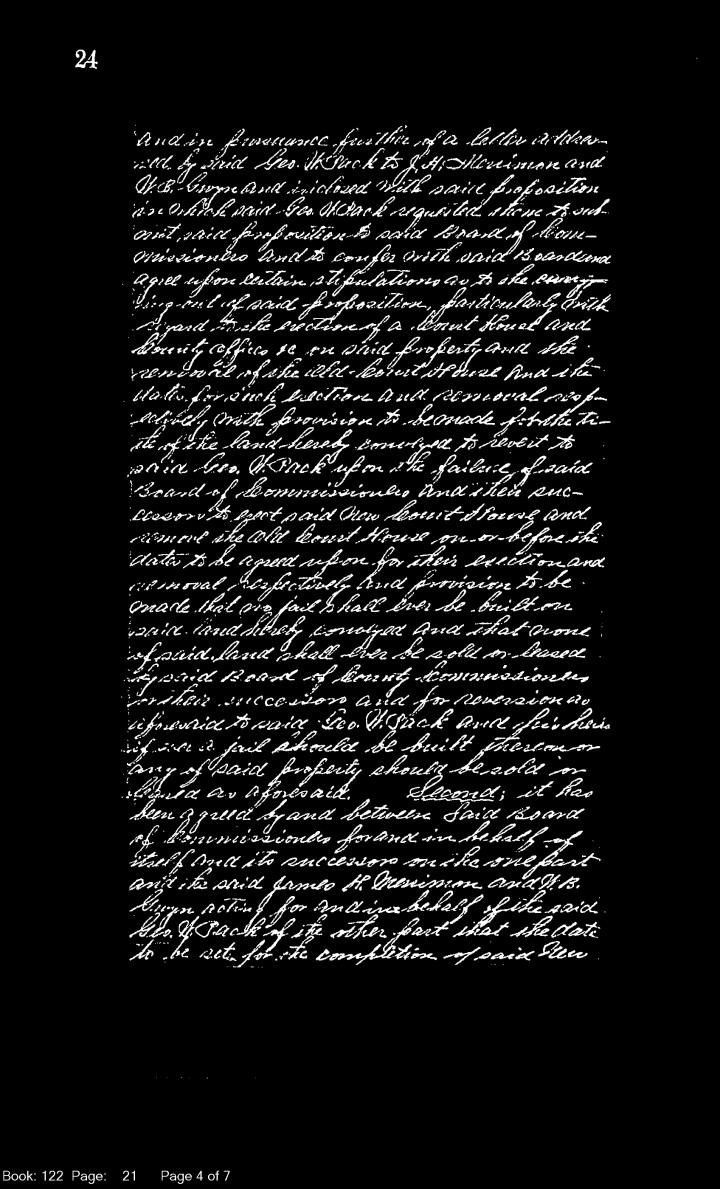

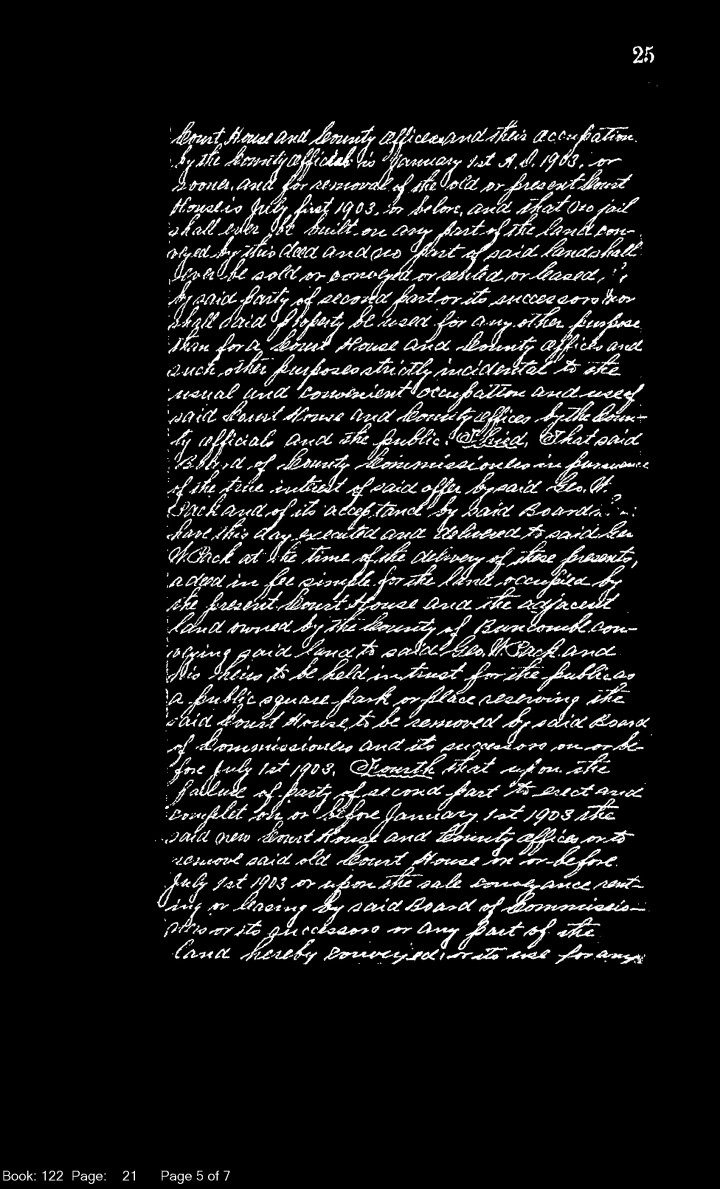

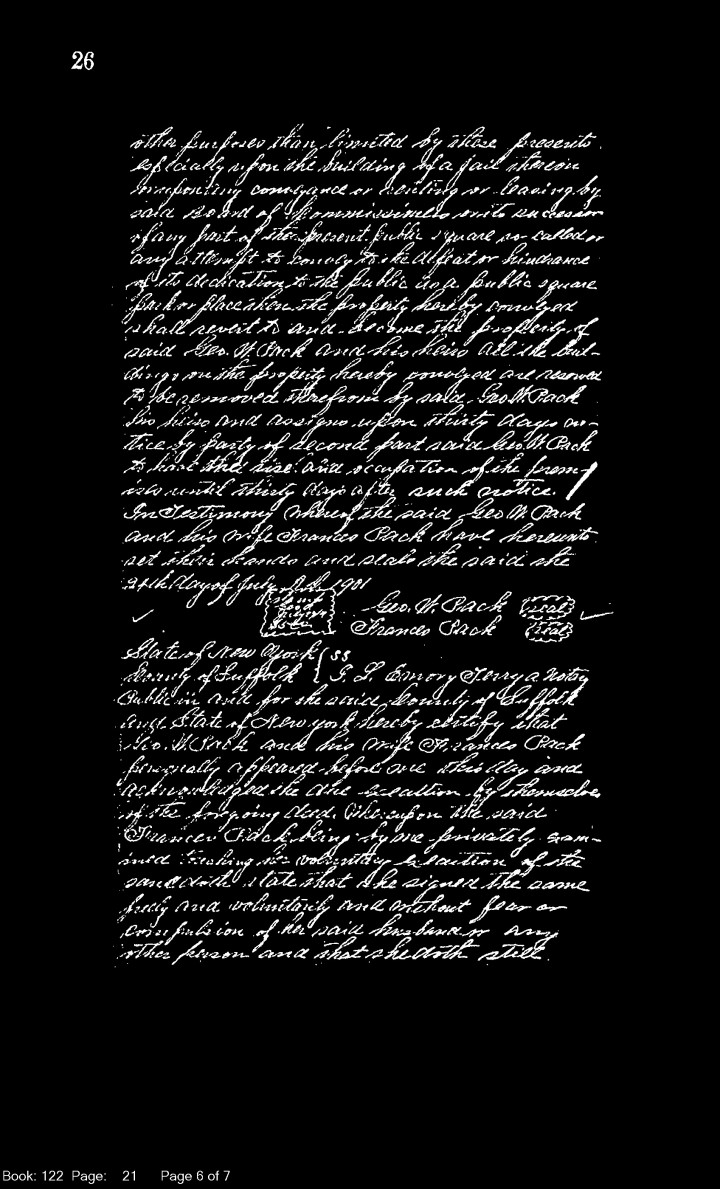

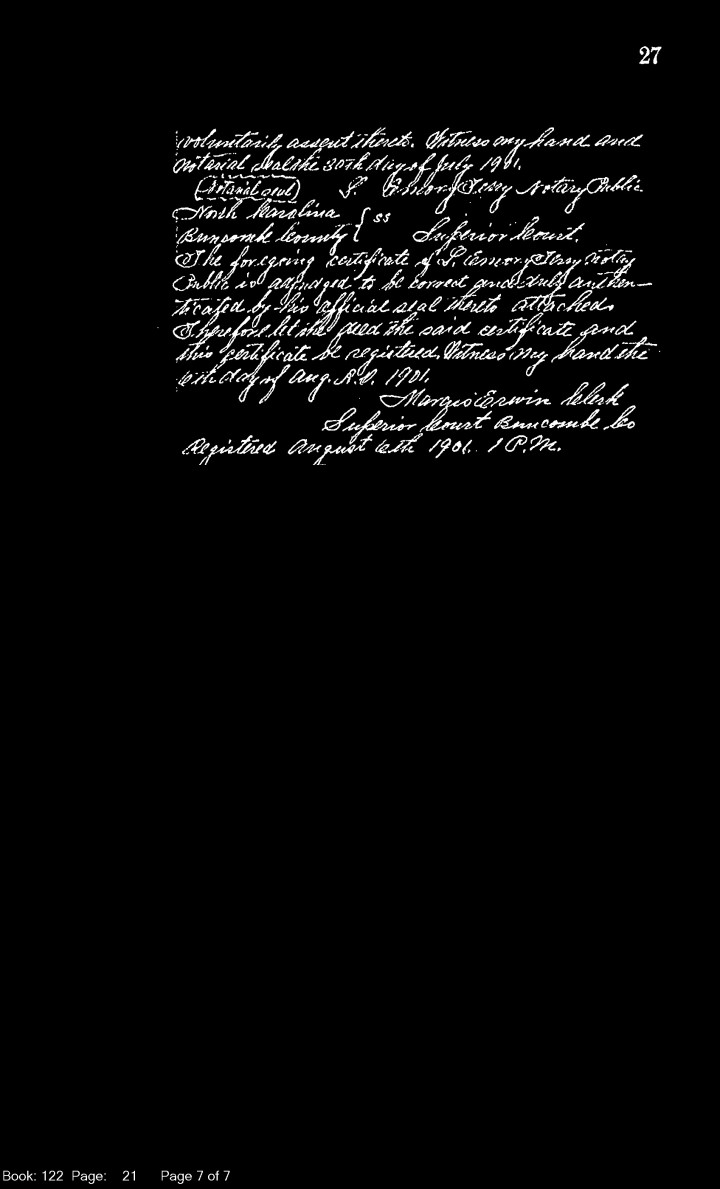

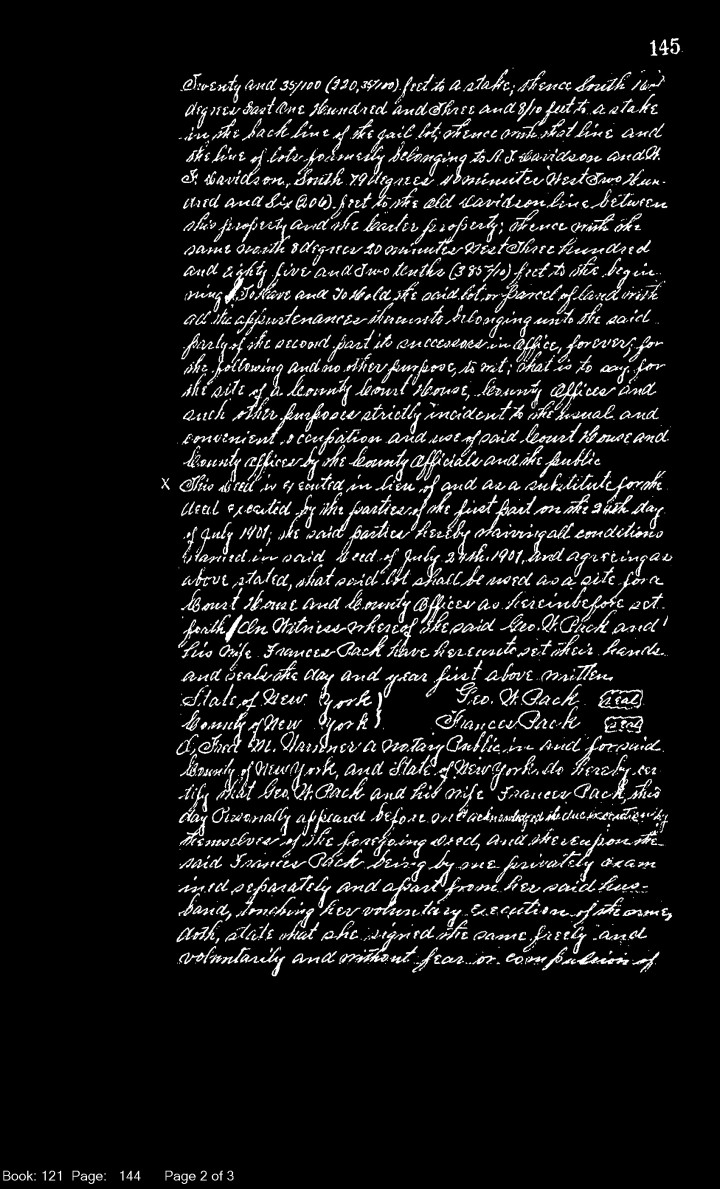

Pack once again came to the county’s aid in July 1901, when he offered the deed to 4 acres behind the courthouse for a fee of $1, for the purposes of building a new courthouse and county building. In return, the county gave Pack “the land occupied by the present Court House and the adjacent land … to be held in trust for the public square park or place” by Pack and his heirs, according to a transcript of the 1901 deed. Photographs and maps from the time show this area most likely included the area where the monuments now stand.

Pack further stipulated that “that no jail shall ever be built on said land hereby conveyed and that none of said land shall ever be sold or leased by said Board of County Commissioners or their successors.” Under this version, the county-owned parcel would mirror Pack’s vision for the old courthouse property on a larger scale: “dedicate[d] to the public forever to be used for the purposes of a public square so called, in Asheville,” according to transcripts of the 1901 deed.

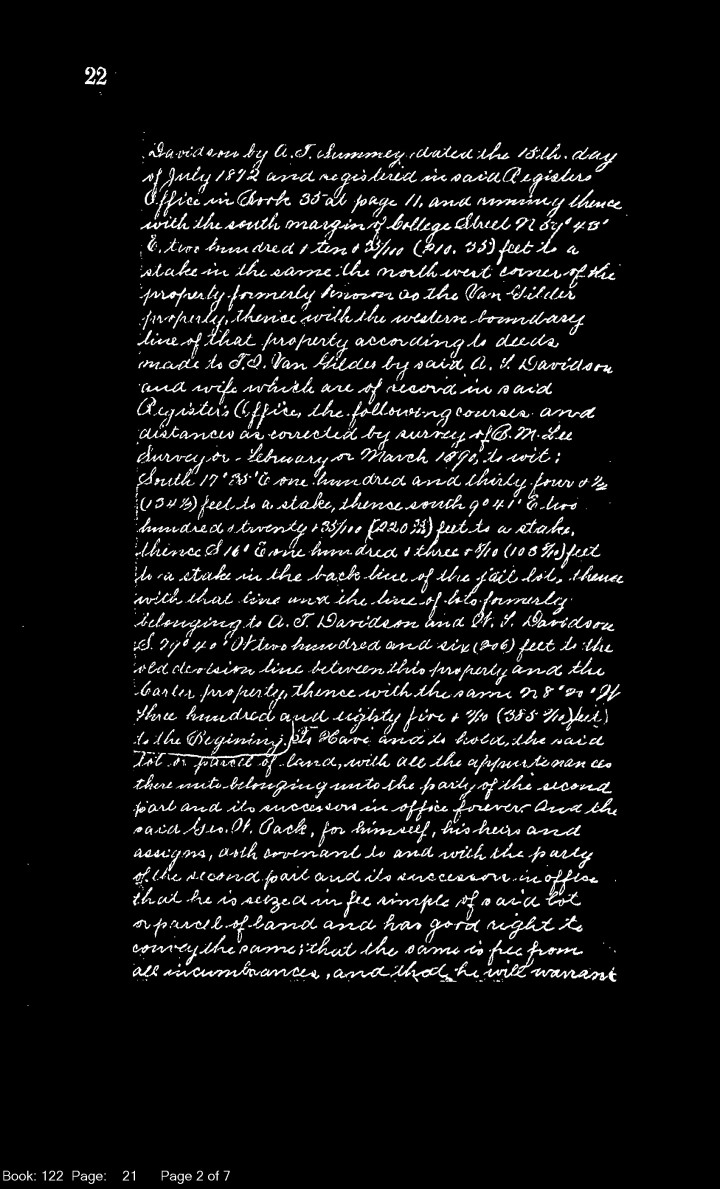

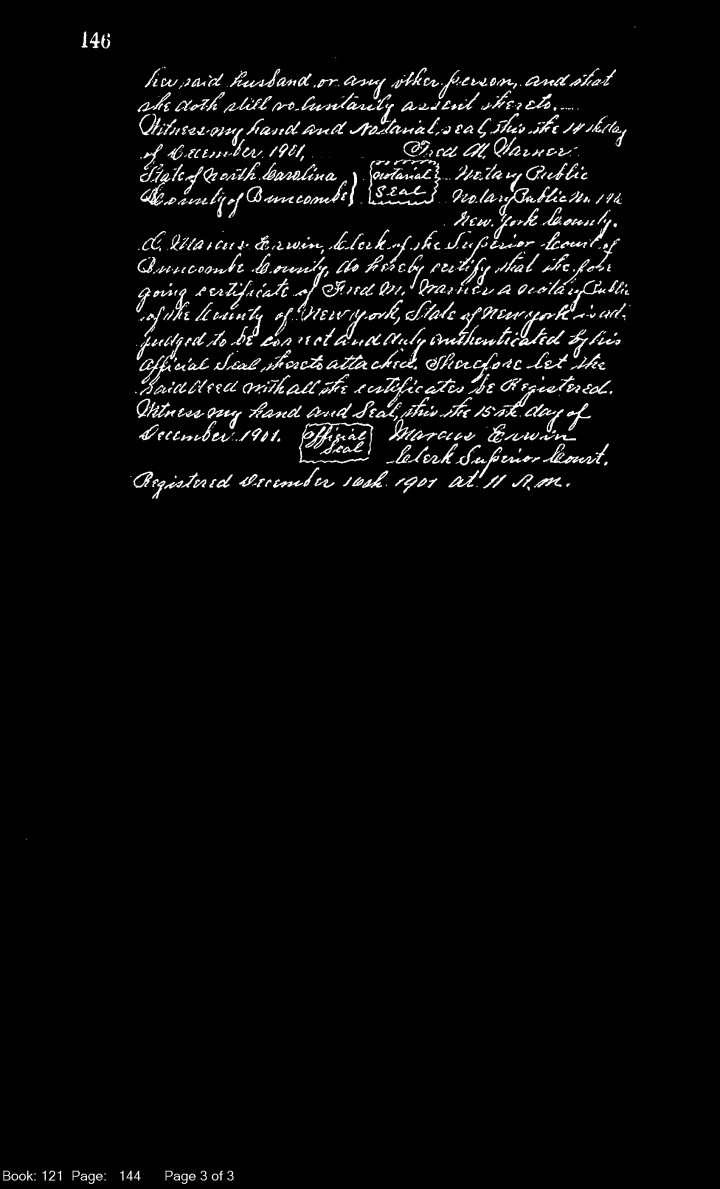

In December of 1901, however, Pack issued a second deed, “executed in lieu of and as a substitute for” the July 24, 1901 deed, in which the language barring a jailhouse on the property sold by Pack to Buncombe County, as well as the provisions that said land be reserved for a public space, were removed. However, the second deed makes no mention of the old courthouse property given to the Pack family, nor is there any indication that the county signed off on this second agreement.

For his contributions to the evolution of this area of Asheville, Pack was commemorated by the city in 1903, when Courthouse Square was rededicated as Pack Place.

No good deed goes undone

As the 20th century progressed, members of the public occasionally called for the removal of the Vance Monument, not on any moral ground but due to its perceived unsightliness. A 1975 WLOS editorial titled, “Vance Monument: Beautiful or Ugly?” determined that “Zeb Vance has far better memorials than this mass of stone,” while Asheville Citizen-Times published citizens’ suggestions to move it closer to the Vance Birthplace, a state historic site in Reems Creek. Nothing seems to have come from these discussions, however.

The two versions of Pack’s cryptic 1901 deed with the county, however, would continue to be a headache for the city and county to the present day. A 1916 Asheville Citizen article, ruminating on the topic, came to the conclusion that “Accepting the deed according to Mr. Pack’s stipulations….It appears that the city has nothing to do with the square except by its agreement to keep and maintain it in order….Pack Square never did belong to the city. The title to it is not in the county, nor in the city, but is vested in the heirs of the late George Pack, to be held by them in trust for the use of the public.”

The city’s intent to develop a portion of Pack Square in the 1920s ran into resistance over whether the project would constitute a violation of the Pack agreement. A similar situation arose again in 2006, when real estate developer Black Dog Realty purchased a portion of Pack Square adjacent to Pack’s Tavern with the intention of building condominiums there. Several residents, claiming to be descendants of George Pack, filed suit against Black Dog Realty and Buncombe County, arguing that the condominium project constituted a breach of Pack’s stipulation that the property remain open to the public.

In 2008, a judge issued a summary judgement in favor of the plaintiffs on the grounds that Buncombe County did not have the right to approve the sale of any portion of the land that would impede public access to the property deeded to the county from Pack in 1901. However, an appeals court ruling in 2009 overturned the initial judgement, according to County Attorney Michael Frue, on the basis that North Carolina law gives authority to counties to manage county land as they see fit. In addition, there is no clear indication that county commissioners serving when Pack completed the deed ever approved all of Pack’s conditions.

The Appeals Court ruling also stated that the plaintiffs were unable to prove they were direct descendants of George Pack, according to the legal reference website findlaw.com. Despite the ruling, the condominium project was abandoned in 2009.

Ghost in the desert

By that time, the known descendants of the Pack family had left Asheville far behind. George Willis Pack died in 1906 in New York; his son and successor, Charles Lathrop Pack, soon became a leading figure in the nascent conservation movement but seems to have had little interest in Asheville’s affairs. Charles’ son Arthur would continue his father and grandfather’s philanthropic work in his chosen home of New Mexico, where he owned the famous Ghost Ranch, which hosted the likes of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Mark Bahti, Arthur Pack’s grandson, says that family stories of George Willis’ land holdings during his time in Asheville took on a more dramatic tone. “We’d heard as kids that George Willis had been asked by the city or the county to hold some land during the Carpetbagger era, because they didn’t want someone else to get a hold of it,” says Bahti, who runs a Native American jewelry gallery, Bahti Indian Arts, out of Tucson, Ariz., and Santa Fe, N.M. “It was good to get that story straightened back out again, a little closer to the facts.”

According to Bahti, Arthur Pack dissolved the family fortune into a variety of charitable organizations and nonprofit ventures prior to his death in 1975. “His goal was to give away every dime before he died; essentially, through his will and his trust, he did that,” he says. However, Bahti is not aware of any title transfers or dealings regarding the Pack family’s rights to Pack Square.

“I’ve been through his papers, and I didn’t run across any reference to it there. I don’t recall his ever having mentioned going to Asheville for anything; that may be why the key paperwork is missing, or not where it should be,” Bahti suggests. “I suspect that it came to his attention and he thought, ‘Good grief,’ and signed off on a quitclaim, which I would assume means returning title to the city or county there.”

A quitclaim deed from 1977 between Buncombe County and the city of Asheville regarding Pack Square would seem to support that idea, but no clear evidence of a certified title indicating what the deed entailed, or what the motivation for its execution was, according to the county attorney Frue.

For his part, Bahti says he’s more than happy to return Pack Square to local ownership, if it turns out his family still retains the rights to it. “If it turned out that it wasn’t properly done, we wouldn’t throw up a tent,” he laughs. “If a quitclaim needed to be issued, we’d certainly be more than happy to oblige.”

Law and order

In the case of the monuments, the 1901 deed offers an intriguing question: If the Pack family did indeed retain the rights to the old courthouse land until Arthur Pack dissolved the family trust in 1975 and did not return ownership to the county or city, is that land considered “public property” under the 2015 law?

“The statute doesn’t specify or distinguish between what kind of public property; it’s just a broad, general term for public property,” says UNC School of Government professor Adam Lovelady, who published an extensive breakdown of the law as it pertains to Confederate monuments. “My read of that would be any property held by the state or a political subdivision of the state — like the DOT or a state park or city- or county-owned property, or potentially even property owned by a water district or some other kind of public authority.”

The landowner is only part of the equation, however, says Lovelady. “The clear thing from the statute is that ownership of the object matters: If it’s owned by the state, certain rules apply; if it’s owned by the city or county, other rules apply; if it’s owned by a private party, and there’s an agreement concerning removal and relocation, then certain rules apply.”

But if determining the ownership of the dirt upon which the Vance Monument and Lee/Connally marker sit is difficult, determining who owns the actual monuments may be nigh impossible without legal action. While Frue declined to offer an on-the-record opinion on the ownership issue, the lack of an official resolution from the county or city of acceptance of the monument leaves doubt around who retains rights over the Vance obelisk and Lee/Connally slab.

The options are many: George Pack provided most of the the funding for the original construction of the Vance Monument, if historical accounts are to be believed, while the Lee/Connally marker was funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In UNC’s statewide Commemorative Landscapes catalog, the city of Asheville is listed as the “custodian” of both monuments, while the latest rededication of the Vance monument in 2015 is to “the people of North Carolina.”

One potential source of clues, if not a definitive answer, might lie hidden in the partially transcribed papers of Pack’s attorney and confidant, Walter B. Gwyn, in UNC Asheville’s Special Collections, says historian Wykle. “There are two volumes of these letters, and they’re an incredible chronicle of the history of Asheville by the man who really was the legal representative and real estate investor for Pack,” she says. “I think, contained within that, there’s a substantial amount of information that has not yet seen the light of day.”

Little things mean a lot

While the mystery of who owns Pack Square and the monuments may not be solved anytime soon, Wykle believes the issue offers residents an opportunity to consider the complex nature of public property and how a community interacts with it.

“It’s like a lot of parks in our country: They’re under constant evolution, though they may visually appear the same,” she says. “I’m more interested in the social and cultural side of that space, how we relate to our public spaces and how we handle ourselves in our civic dialogues. Really taking a look at how we relate to our public spaces, and what those mean in terms of civic education, might be more instructive than pulling forward the arguments and litigation again.”

Unfortunately, it might just take litigation to get some concise answers on how that property, and others across the state, will be handled in light of the 2015 statute, Lovelady says. “Given the current events and the discussions that are going on, there’s a lot of interest in trying to figure out how this law applies, and what it means,” he says, “but there’s not any case law to help us figure that out.”

Reisinger hopes that city and county attorneys will be able to come to a consensus on the property in the near future. “We need to first agree on owns this property before we answer the question of how we are going to deal with our Confederate monuments in light of the tragedy in Charlottesville,” he says. “I hope the City and County attorneys can give you, and their respective boards, a concrete answer on this issue soon.”

Ironically, the Pack family coat of arms alludes to the very kinds of complications that George Willis Pack’s 1901 deed presents. “The inscription, ‘Le pire ennemi du bien est la peu pres,’” wrote Wykle in her 2006 study of Pack Square’s history, “basically reads ‘It’s the little things that will get you.’”

One wonders if Pack ever imagined how prophetic that motto would be.

An excellent story, thoroughly researched, thoroughly reported. A public service to have published this. It adds greatly to the conversation about the monument.

Given that one of Asheville’s greatest benefactors, George Willis Pack, commissioned and paid for the Vance Monument in honor of his friend, Zebulon Vance, and that Pack, an anti-slavery advocate could wish to honor Pack this way, it would be disrespectful to Pack to remove the monument. The Jefferson Davis-Robert E. Lee monument should go. Keep the Vance-Pack Monument for what it means to the history of this city. It’s as much a monument for Pack as it is for Vance.

Thanks for a reasoned reply to an interesting issue.

Great report. Happy to give $10 a month. I’m getting a great deal !

I say keep the monument as it’s a wonderful phallic example of our patriarchal history.

The Cherokee indigenous people.