by Kristin D’Agostino

In 1892, author George Chapin published the book Health Resorts of the South. Not surprisingly, it included a chapter on Asheville. The section began with a quote by poet John Greenleaf Whittier: “And the pale health seeker findeth there/the wine of life in the pleasant air.”

At that time of the book’s publication, the world was in the throes of one of history’s deadliest diseases: tuberculosis. In the 19th century it’s estimated that the disease killed 7 million people per year. Highly contagious, doctors believed symptoms — which included debilitating pain in the lungs and coughing up blood — could be controlled by bed rest and time spent in the mountains.

“The idea was that illness could be contracted through miasma or ‘bad air,’” says Katherine Cutshall, manager at Buncombe County Special Collections at Pack Memorial Library. As the U.S. became more industrialized, she continues, “physicians recommended their patients seek fresh clean air.”

According to Cutshall, the Cherokee once frequented area hot springs for health benefits and restorative qualities. Later, in the 1770s, the region’s first white settlers held similar beliefs about the region’s wellness features.

By 1871, Dr. Horatio P. Gatchell established The Villa in Asheville, the nation’s first sanitarium. Originally located in the Kenilworth section of Asheville, Gatchell later relocated the facility to Haywood and College streets. Once established, the doctor collaborated closely with outdoor enthusiast (and future Asheville mayor) E.J. Aston to promote his new health resort in the pamphlet Western North Carolina: Its Resources, Climate, Climate, Scenery and Salubrity. The brochure compared Asheville’s mountains to those in Vienna and Geneva, popular destinations in Europe to treat individuals with TB.

The city’s 1896-97 directory asserted that in New England, 1-in-4 deaths were due to consumption; but in Western North Carolina, the directory asserted, the figure was 1-in-33. Medical minds of the time attributed the region’s healing properties to the city’s elevation, which they claimed created air pressure that matched that in human blood vessels.

Asheville was quickly becoming a hub for medical tourism. At its peak the city had 130 boardinghouses and sanitariums. This appeal eventually led to the arrival of E.W. Grove, whose impact on the city is present to this day.

‘Never too old to build castles’

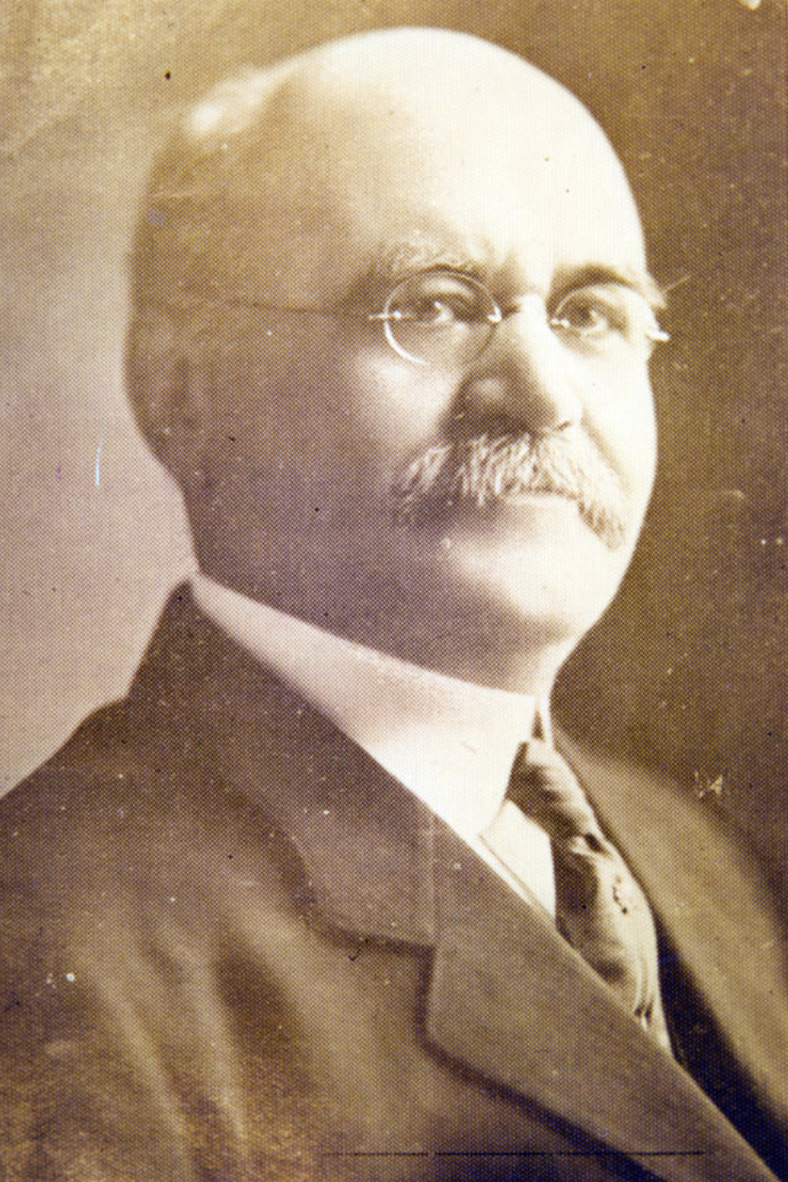

In the 1880s, before his arrival in Asheville, Grove was building his reputation in the medical world as a young pharmacist in Paris, Tenn. At the time, malaria was taking the South by storm. Grove’s first wife, Mary Louisa Moore, and his daughter, Irma, both died from the illness.

Quinine, a plant-derived medicine with a strong bitter taste, was known to help curb malarial fevers and chills. Determined to make the solution more palatable, Grove created a sweet syrup with lemon flavoring and marketed it as a tasteless chill tonic. The product bore an eye-catching label: a half-child, half-pig smiled at consumers; beneath the creature the label read, “Grove’s Tasteless Chill Tonic. Makes Children and Adults Fat as Pigs.” According to Omni Grove Park Inn’s website, Grove eventually sold over 1.5 million bottles.

Health issues ultimately led Grove to relocate to Asheville. In 1897, he built a summer home in the city. By 1905, he began exploring development opportunities in the area, amassing hundreds of acres in North Asheville.

Then, seeing an opportunity to capitalize on the city’s blossoming tourism trade, Grove set out to build a world-class luxury hotel on Sunset Mountain. However, there was one big problem. The elite travelers who had been coming to Asheville since the completion of the railroad in 1880 were weary of the city’s growing reputation as a national TB sanitarium.

“The disease carried a massive stigma,” says Cutshall. “It was associated with uncleanliness and poverty. Grove wanted his resort to be for pleasure, not for sickness. … He went as far as purchasing area boardinghouses and sanitariums only to tear them down as part of his efforts to dissociate his resort from the area’s reputation as a health resort.”

In the end, Grove’s vision won out. According to writer K.C. Cronin, the city ceased marketing itself as a national TB sanitarium; Grove and his son-in-law Fred Seely completed their plans for the Grove Park Inn.

The hotel’s groundbreaking ceremonies took place on July 9, 1912. The following year, on July 12, 1913, it opened. The Asheville Gazette-News reported the inn’s completion. In its July 14, 1913, edition, the paper featured an excerpt from a speech Grove offered guests during the inn’s opening night ceremony:

“A man is never too old to build castles and dream dreams. Standing here tonight in the midst of my friends and invited guests, I find a dream realized and a castle materialized.

“After a long mountain walk one evening, at the sunset hour, scarcely more than a year ago, I sat down here to rest, and while almost entranced by the panorama of these encircling mountains and a restful outlook upon green fields, the dreams of an old-time inn came to me — an inn whose exterior, and interior as well, should present a home-like and wholesome simplicity, whose hospitable doors should ever be open wide, inviting the traveler to rest awhile, shut in from the busy world outside.

“It affords me far more gratification than I can express in having in my immediate family an architect and builder who, by his artistic conception, by his untiring zeal, has studied out the very minutest details, making my dream a reality indeed and accomplishing what in so short a time, seems almost beyond human endurance.”

Grove went on to leave his mark on downtown Asheville with the construction of such buildings as the Grove Arcade and the Battery Park Hotel. When Grove died in 1927, he was buried in his family plot in Paris, Tenn.

His medicine company — complete with its cure-all chill tonic — would long outlive him. The business was renamed Grove Laboratories in 1934. And though the pig body would eventually be removed from its advertisements, the baby’s face remained a key feature when Bristol-Meyers bought out the company in 1957.

“The elite travelers who had been coming to Asheville since the completion of the railroad in 1880 were weary of the city’s growing reputation as a national TB sanitarium.

The disease carried a massive stigma,” says Cutshall. “It was associated with uncleanliness and poverty. Grove wanted his resort to be for pleasure, not for sickness. …”He (Grove) went as far as purchasing area boardinghouses and sanitariums only to tear them down as part of his efforts to dissociate his resort from the area’s reputation as a health resort.”

Look at this man Grove’s morality. Maybe we should tear down the Grove Park Inn.

Well, at least it wasn’t about the Sullivan Act.