On Jan. 15, 1863, amid the Civil War, The Asheville News reported that enemies, “not in the shape of Northern soldiers, but … of disloyal men from Tennessee and our own State,” ransacked the nearby town of Marshall. Confederate soldiers, the article noted, were headed to Madison County to “restore order and security.”

Additional information, the paper continued, “will be fully known in due time.”

Subsequent reports explained how the region’s Union sympathizers, including those living in Shelton Laurel, were denied salt from Confederate commissioners. With food in short supply and salt critical for preserving meat, individuals took matters into their own hands.

Two months later, on March 17, 1863, The North Carolina Standard, based in Raleigh, shared an account from an unnamed source residing in the state’s western region. According to the individual, Confederate soldiers “shot down in cold blood” a number of Shelton Laurel residents accused of the January raid.

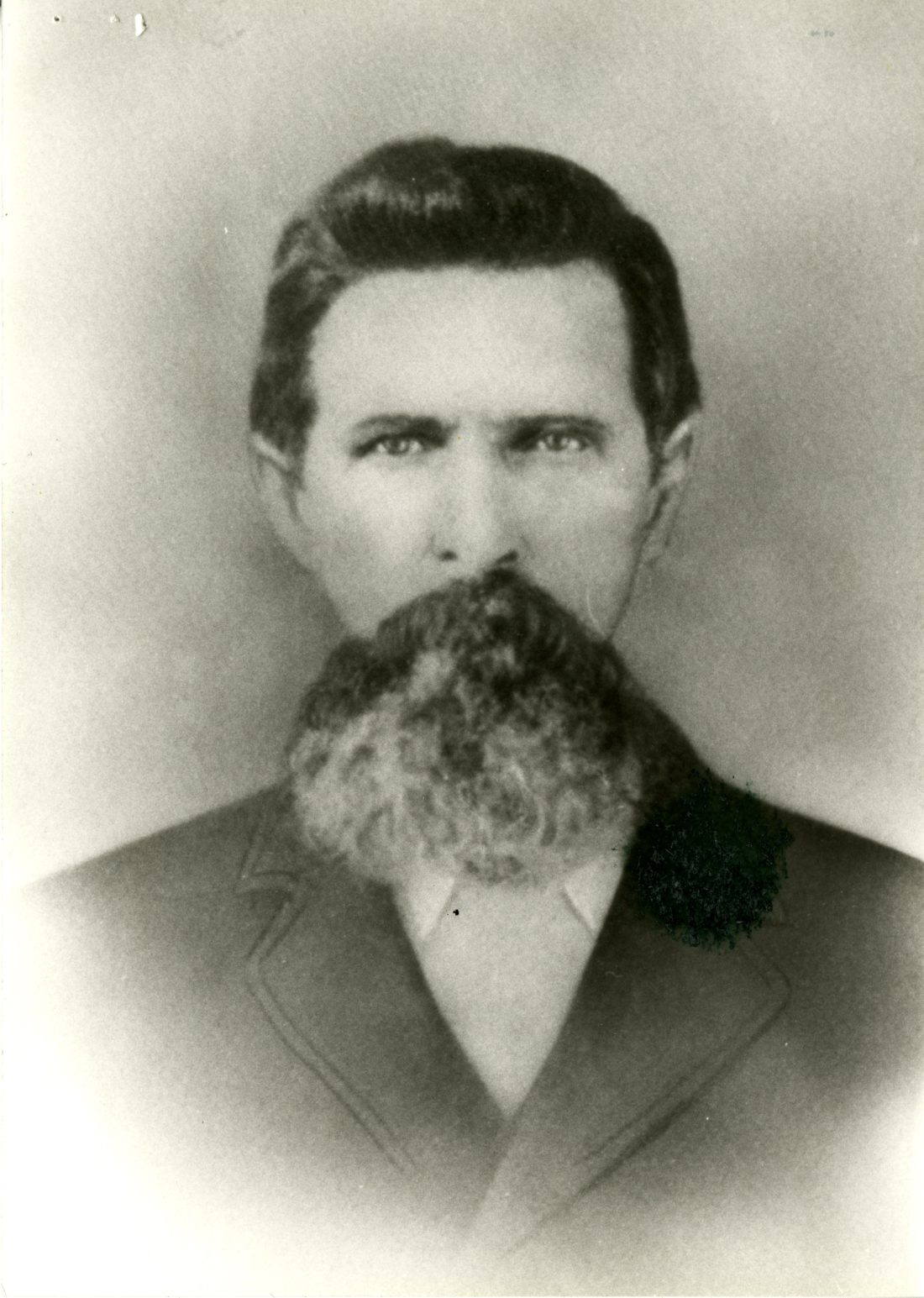

The source asserted that the officer who ordered the executions (identified in subsequent papers as Lt. Col. James Keith) “knew that the only object of the raid made by these [Shelton Laurel] men was to seize the salt, which they believed was wrongfully withheld from them.”

“I am no apologist for these miserable ignorant thieves,” the source continued. “But I hold that the Constitution and the laws of this country guarantee to every man and woman in the Confederacy, no matter what their crime, a fair and impartial trial.”

The North Carolina Standard agreed. The men accused of the raid “committed a great wrong against society,” the paper wrote. Along with the stolen salt, the article noted damage to private property and at least two wounded residents.

The men deserved lawful punishment, The North Carolina Standard continued. But instead, the paper observed: “The musket did the work. The red hand of vengeance was triumphant, and the voice of mercy, which is heard everywhere except in hell, was raised in vain.”

Because these men were denied a trial, the paper deemed the 64th Regiment’s actions “both cowardly and wicked.”

By the summer of 1863 several newspapers — including the Baltimore Sun and The New York Times — picked up on the story and ran a syndicated article describing the January killing of the 13 men and boys, which became known as the Shelton Laurel Massacre.

The piece features gruesome and dramatic details about the executions, including alleged pleas made by one of the youngest victims, 12-year-old William Shelton.

“Poor little Billy was wounded in both arms. He ran to an officer, clasped him around his legs, and besought him to spare his life. ‘You have killed my father and my three brothers; you have shot me in both arms — I forgive you for all this; I can get well. Let me go home to my mother and sisters.’ What a heart of adamant the man must have who could disregard such an appeal! The little boy was dragged back to the place of execution; again the terrible word ‘fire!’ was given, and he fell dead, eight balls having entered his body.”

The syndicated report went on to note that a number of Shelton Laurel women were also brutally “whipped and hung by the neck till they were almost dead.” Among the assault victims was an 85-year-old resident. “And the men who did this were called soldiers!” the article decried.

No members of the North Carolina 64th Regiment were ever tried for the deaths of the 13 people killed in Madison County on Jan. 19, 1863.

Today, the Shelton Laurel Massacre continues to inspire debate, research and publications, including the most recent work of historical fiction And the Crows Took Their Eyes by local author Vicki Lane. (See “Author Vicki Lane Takes Multiple Views of the Shelton Laurel Massacre,” Oct. 23, Xpress)

Editor’s note: Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation are preserved from the original document.

UPDATED: The article’s photo caption was updated on Nov. 9 to more accurately describe Keith’s role in the massacre.

Actually Lt Col Keith WAS tried, and convicted for the massacre. Though Governor Vance sent the State Attorney General, Merrimon, to investigate during the war, by the time the facts were known the 64th NC was out of the state. Civilian courts were not operating in most places, so getting an extradition hearing was impossible with the war on. The new state Constitution was accepted in 1868 and civilian government resumed, and straightaway Keith was indicted for thirteen counts of murder. His lawyers obtained a change of venue, to Buncombe County. Keith was tried, for simplicity’s sake, at first only for the best case prosecutors thought they could make, and was promptly convicted. Keith appealed to the state Supreme Court, and pending this appeal was lodged in the county jail, little better than a log pen on College Street. The state Supreme Court rendered its opinion, and advised that this was all a waste of time, as even before Keith was indicted President Johnson had issued a blanket pardon covering all parties of any side for anything and everything they had done during the war. This covered Keith’s case, so no conviction could be sustained against him for any of this episode, nor against any other participant in the massacre. Keith had not waited for this result, and had escaped from the Buncombe County jail and disappeared. About thirty-five years later he returned to the area, and told of his alleged adventures in Mexico, and circulated a pamphlet in which he claimed to have killed a man in a gunfight or duel in defense of the virtues of southern womanhood. Nobody was too impressed or interested and he disappeared again, to what ultimate fate no one knows. It should be pointed out that Keith was not the commander of the 64th NC. Keith was second in command, the lieutenant colonel, with Lawrence M. Allen of Marshall as the colonel. When the salt riot took place in Marshall Allen’s two children were sick and dying of scarlet fever in his home there (Allen was away with the army) and the rioters entered his home and took the sheets and blankets off the dying children, who did go ahead and die. About half of the 64th NC was companies raised in Madison County, men who had known or known of the Sheltons all their lives. This incident with the colonel’s dead children did not sit well. The Sheltons, who with their kin had been almost all the salt rioters, lived on Little Laurel Creek, also know as Shelton Laurel. The top of the valley containing the creek is at the Tennessee line. (In 1797 the boundary line surveying party marking this boundary found the first two Sheltons already there when they got to the top of Little Laurel, these being Roderick “Stob Rod” and his brother, Coonrod, one living in a cave, the other in a hollow tree). The plan of the portion of the 64th NC involved was a good one. Part of them would circle around and get up on the ridge and move to the top of Little Laurel, to cut off escape in that direction. The rest would enter the valley from below and come up the creek. This lower party was shot at twice from ambush as the operation began. They did take a rope and throw it over a branch and put one end around the neck of an old woman, and hoisted her up until her shoe tips were scuffing dirt. But then they let her go, and she probably knew nothing to tell them anyway other than the ones that they were hunting were in the bushes somewhere. They caught fourteen men and boys, and put them in a corn crib to keep overnight. At the time Madison was in the Department of Western North Carolina and East Tennessee, with headquarters at Knoxville, so they were going to have to walk these fourteen to Knoxville. Instead, they decided to shoot them. The next morning when they were called to come out, the youngest boy held back and hid, so it was thirteen that got marched down the road about a mile, made to kneel, and shot in the back of the head, and buried in one single mass grave. Some years after the war the Federal government passed pension legislation, and the survivors of these thirteen filed a claim (by now embellishing just a bit and alleging that their homes were burned too, as they watched their menfolk killed). Zeb Vance and Augustus Merrimon happily endorsed their petition, willing to let them collect a pension if they could obtain one. The problem was that to collect a survivor’s pension the deceased needed to have been a member of the armed forces of the United States. So the surviving Sheltons went ahead and said they WERE members of the armed forces of the United States, having enlisted one another in 1861 (when the youngest was 10) and made a stab then at getting through to Union territory, but had to turn back and go home, where they held themselves in instant readiness for their chance. In fact, at least one of these thirteen was a deserter from Company B of the 29th NC, this being a newer Stob Rod Shelton. There were other incidents around of meanness during the war. Colonel Walker of the Thomas Legion was home on sick leave at Murphy when a party took him from the dinner table with his family. His wife ran after and found him murdered in the road. Captain Edney’s father, of Hendersonville, was old Captain Edney, having been for many years a captain in the militia. In a case of mistaken identity a party called for Captain Edney to come out and shot him dead on his doorstep. People knew who did these things, but they let it lie, and usually the names of the perpetrators died with the people who knew them.

Thanks for the additional insight, Kevin. I adjusted the photo caption to more accurately reflect Keith’s role.

According to the 2006 Encyclopedia of North Carolina, published by UNC Press and edited by William S. Powell, no one stood trial for the killings. Please note, my response here is not to call into question your research, just to note where my information came from.

With that said, after reading your comment I did reach out to author Vicki Lane and she agrees with your assessment that Keith did go to trial for one of the 13 killings. But according to Lane, he was not convicted. The author notes she is not an expert on the topic. Lane also points out that there are many discrepancies among the earliest accounts of the massacre.

Again, thanks for the information shared and thanks for reading Xpress.

State v. Keith, 63 N.C. 140 (N.C. 1869). Its not entirely clear from the opinion but it is possible that the trial judge allowed Keith an interlocutory appeal (before a judgment was entered) from the trial judge’s denial of Keith’s claims under the Amnesty Act, that he had been pardoned, because that Amnesty Act had been repealed. However the state Supreme Court held here that, once pardoned, you cannot be unpardoned, and ordered the prisoner freed.

Also I should mention that the Shelton Laurel Massacre was possibly the subject of two lengthy inquiries by the military justice system. The North Carolina courts remained open, so the Confederate military courts had to find a home other than the county courthouse, which they did in the Asheville Military Academy, on Academy Street (today Montford Avenue, and William Randolph School stands on this property). The colonel of the 29th NC was in Asheville for almost a year, and conducted two what were described as “courts martial”, one lasting from January through April, 1864, and the next from April through September 1864. These are VERY LONG for military proceedings. No record of the proceedings survive, and there are only oblique references that I have ever been able to find, hinting at inquiry into the Shelton Laurel Massacre.

Mr. Calder,

An excellent resource you should consider for future pieces regarding Appalachian history is Mr. Michael C. Hardy. You won’t be disappointed.

Thank you for the recommendation and thanks for reading Xpress!

Mr. Calder, that was a fine article! I sure wish that some day the old Asheville News of 1863 would show up! I’m sure it would give plenty of initial reactions to the massacre – although quite different than the New York Times article. We do have some reactions from the southern perspective. Here are a few examples: January 20, 1863 – “I have heard nothing from the Laurel war yet. Hope to hear soon of the tories being exterminated.” January 22, 1863 – “We have killed some 30 tories & taken 16 prisoners. We have a force of over a thousand men in the tory region.” January 25, 1863 – “A good many tories have been killed by Col. Allen’s Regiment. I hope they may exterminate them this time.” (Cornelia Henry journal). January 26, 1863 – “The militia of Madison and Yancey were also on hand, and the authorities are determined to make clean work of it. . . Their recent outrages called for severe punishment, which we do not doubt they have received before now.” (The Daily Progress, Raleigh, NC). January 28, 1863 – “The number engaged in the outbreak did not in my opinion exceed fifty or sixty. But there is no doubt a considerable number of renegades scattered over the mountains. The guilty have in part [or fact?] been punished, and the remainder are dispersed.” (Col. William H. Thomas to his wife, from Warm Springs, NC). May 18, 1863 – “SIR: I had the honor to request of you some time since an examination into the case of Lieut. Col. J. A. Keith, Sixty-fourth North Carolina Troops, charged with the murder of some unarmed prisoners and little boys during the recent troubles in the mountains of this State. I have heard by rumor only that he was brought before a court-martial and honorably acquitted by producing an order for his conduct from General Davis, commanding in East Tennessee. I have also been officially notified of his resignation. Will it be consistent with your sense of duty to furnish me a copy of the proceedings of the court-martial in his case? Murder is a crime against the common law in this State and he is now subject to that law.” (Governor Z. B. Vance to James A. Seddon, Secretary of War). Vance got it right by saying “by rumor only.” There was never a court-martial of James Keith. Keith was not indicted for 13 murders – only 6 or 7. According to a newspaper of the time, he was tried on one case and found not guilty.

Thanks for all this, Dan. Fascinating!

It is seldom necessary for a defendant in a criminal trial to appeal to the state Supreme Court when he has already been acquitted. These things are, in some degree, POSSIBLE: 1) Keith had been acquitted of the one charge upon which he was tried but remained in custody on the other charges, so he had nothing to appeal yet, but given the novel circumstances both the trial court and the Supreme Court agreed to allow his appeal to proceed; or 2) having ruled against Keith in his trial on the issues of amnesty and immunity the trial judge agreed to halt the proceedings in the middle of the trial to allow Keith to appeal this specific issue to the state Supreme Court, and they’d all wait around for a few months for the matter to be decided in Raleigh, if the Supreme Court cooperated and took the case for decision. However, quoting from the opinion is State v. Keith, 63 N.C. 140 (N.C. 1869), “The prisoner was held under seven different charges of murder. The case stated that this was an indictment for the murder of Roderic Shelton, in Madison county…As several other indictments against the prisoner are somewhat loosely referred to in the transcript of the record sent to this Court; it is proper to say, that the indictment against him for the murder of Roderick Shelton, is the only one which appears to have been adjudicated in the Superior Court, and it is the only one which is in this Court.” APPEARS TO HAVE BEEN adjudicated, not, “is pending” or “held in abeyance pending our decision”, and moreover of necessity has been adjudicated in such a way as to provide the defendant grounds for appeal, which would be a guilty verdict. And the final words of the opinion in State v. Keith , 63 N.C. 140 (1869) are these: “Judgment reversed.” Meaning there WAS a judgment, and it was reversed, and the prisoner discharged.

Hey Kevin, thanks as always for the additional information here and elsewhere on the thread.

Mr. White, I appreciate your interest and input with this story. It was the Raleigh Standard of Feb. 22, 1869 that said Keith was acquitted for the murder of James Shelton, Jr., but was still held in jail for other cases. (May be fact – may not be). From reading the Supreme Court decision, it looked to me like that during the trial of Roderick Shelton, Keith’s lawyer made motion to “discharge the prisoner” due to the Amnesty Act. The Judge refused, and Keith appealed. Supreme Court decision was , “We think the Judge should have discharged the prisoner. Let this opinion be certified, &c. Per Curiam Judgement reversed.” Keith actually broke out of Asheville jail just days before the decision was known. He ended up in Arkansas. Col. Allen also fled to Arkansas (with other Madison County men) just after the war ended. It was actually Col. Allen instead of Lt. Col. Keith that had the phamplet published, “Partisan Campaigns of Col. Lawrence M. Allen,” (the short title) detailing Allen’s duel in Mexico and other incidents (some true, some not). Some of those 13 killed were deserters of Allen and Keith’s 64th NC. We’ll never know the full truth of what happened in January 1863 in Shelton Laurel.

In 1868, just as today, trial judges for ample good reasons were and are reluctant to allow appeal to a higher court before conclusion of the trial. Having once empaneled a jury and begun to take evidence, then as now, the defendant can take exception to rulings of the trial judge, and, should he lose, make his exceptions the basis of an appeal. What the Supreme Court reversed here is a judgment, and a judgment is the final result of a trial. It was not a ruling that was reversed, some decision of the trial judge on the way to a judgment, but an adjudicated judgment of guilt for the murder of Roderick Shelton. Keith may have subsequently actually been acquitted for the murder of James Shelton, Jr., but, had he been found guilty of murdering James Shelton, Jr., that conviction too would have been vacated on appeal if the Supreme Court adhered to the reasoning given in State v. Keith, and there is no reason to think that Court would have changed its thinking, given the rationale set forth in State v. Keith. Moreover the announced rationale in State v. Keith makes plain that any attempt to prosecute any participant in the Shelton Laurel Massacre for the murders would be fruitless. And at any rate it is not correct to assert that no member of the 64th NC was ever prosecuted for the murders, implying that the civil and military authorities were willing to countenance murder depending upon just who it was that was killed, both during and after the war.

Mr. White, I must apologize for my statement above: “From reading the Supreme Court decision, it looked to me like that during the trial of Roderick Shelton, Keith’s lawyer made motion to “discharge the prisoner” due to the Amnesty Act. The Judge refused, and Keith appealed.” I just re-read transcripts of the Roderick Shelton case from Madison Co. to Buncombe Co. ( got them years ago from State Archives). The records were not of a TRIAL, but of an INDICTMENT. The motion to discharge Keith was made in Buncombe court after the Indictment in Madison. I have no record that a TRIAL for the murder of Roderick Shelton ever took place. If you like, I can send you records I have.

I would love to see your records, Mr Slagle. You’ve obviously put a lot of thought and time into trying to resolve the issues. Again, I do not know that a mere indictment would be “ripe” for appeal. Typically what would happen would be defendant’s counsel made his motion and raised the issue, but was unsuccessful, and counsel then noted for the record his exception to the ruling. Typically only those issues to which a party objected during trial, but had their objections overruled, then took an exception to for the record, could be raised on appeal. Probably this pleading of the Amnesty Act was a pretrial motion, immediately before the trial. The Supreme Court would not have spoken of a “judgment”, which has a specific legal meaning, if there were not one. You can reach me at kjw796158@gmail.com.

Some papers sent. What you say makes perfect sense. But the key, I think is wording in decision – “… it is proper to say, that the indictment against him for the murder of Roderick Shelton, is the only one which APPEARS TO HAVE BEEN adjudicated in the Superior Court. . . ” Appears to have been adjudicated vs. WAS adjudicated? Seems he was not sure.

After reviewing the papers you sent I agree with you. Keith made his motion claiming Amnesty, was denied, and the trial court was willing for him to go ahead and appeal at this preliminary stage, to obtain clarification of the state of the law. And the Supreme Court “allowed his appeal” (without requiring an appeal bond) because they wanted to make crystal clear that though the Amnesty Act might have been repealed, the instant it had been enacted all members of the service were immediately pardoned for anything they had done, or not done during the war, and this Amnesty and pardon was still in effect, even if the law that accomplished this result had been repealed. Which leads to the further idea that if Keith had in fact been acquitted for the murder of James Shelton, Jr., it must have been before this indictment for the murder of Roderick Shelton came up on the docket, because the solicitor and the judge would have known better after the result in this case than to bother to attempt further prosecution.

My ancestors were members of the 64th NC, conscripted from across the TN state line (barely) living on the other side of Shelton Laurel on Viking Mountain, literally a 30 minute hike away. Just wanted to note that a large body of the 64th surrendered to the 13thTN Cal in 1863 in a battle at Cumberland Gap. Most of the men who surrendered then joined the Union Army for the rest of the war, including my two ancestors. Some of the men who surrendered did not join the Union Army and instead were sent to prison at Camp Douglas. To myself, this shows proof that many of the men in the 64th did not support Kirk and his actions, as they risked imprisonment rather then to continue serving the Confederacy under a man who massacred their neighbors and kin. Just a thought.

R. Pierson, would you mind sharing names of your ancestors in the 64th? There was not a ‘battle’ at the Gap in Sept. 1863 – the Confederate General Frazier just saw it prudent to surrender.

Thank you for clarifying that there was not a battle. That may have been something that I assumed took place.

I am a decendent of William and James Oscar Payne, who were brothers. William and most of his family moved to the Fayetteville, Ark. area in the decades following the war. James had severe rheumatism, so he and most of his children stayed around Greene and Washington Co., Tenn. area. At one of the older family cemeteries, you can literally look up and see the TN/NC line with Shelton Laurel located just on the other side of the mountaintop.