This week’s column is an accompaniment to the preview article on historian Karen Cox’s upcoming Pack Memorial Library presentation, “Confederate Monuments in the Jim Crow South” (see “Dixie’s Daughters: Historian Karen Cox confronts Confederate monuments,” May 16, Xpress).

Among her many talking points, Cox will address the South’s “Lost Cause” narrative, which took shape in the aftermath of the Civil War. From textbooks to newspapers, from monuments to public orations, the Lost Cause mythology sought to present the Confederates’ wartime efforts not as one of defeat, but of heroism in the face of great odds. The campaign also aimed to reimagine slavery as both a benign and beneficial institution.

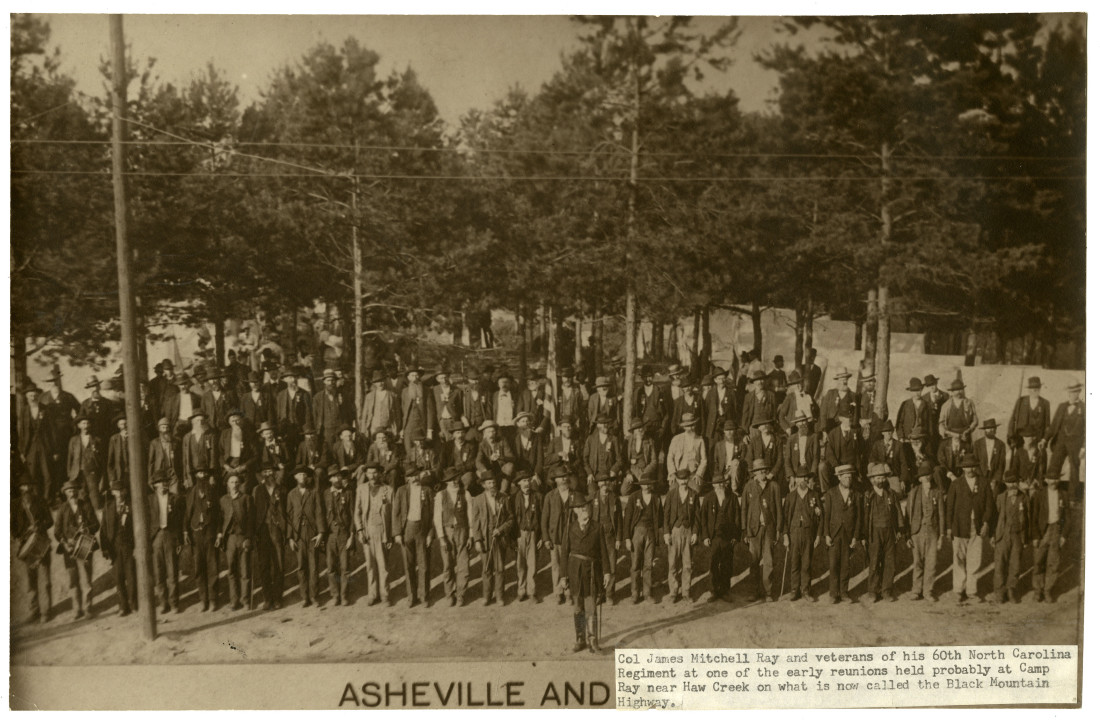

On Oct. 10, 1893, a crowd of veterans boarded the westbound train, leaving Asheville for Waynesville to attend the annual reunion and encampment of the Western North Carolina Confederate Veterans’ Association. The Asheville Weekly Citizen recapped the gathering in its Oct. 19, 1893, edition. Among the highlights, the newspaper included a talk given by Col. James Mitchell Ray of the 60th N.C. Regiment, who proclaimed:

“’Tis said ours was a lost cause. Again saw we, Nay! The effort to establish slavery was lost, the lives of thousands of true and gallant braves lost, but the greatest of all for which we so ably fought, the rights of a minority as against the usurpations of a grasping, tyrannical majority, was not lost … The gallant and stubborn fight we made will serve as a salutary warning to usurpers for all time to come.”

Similar sentiment would echo for decades to come. In addition to highlighting wartime valor against an imposing federal government, the Lost Cause narrative often portrayed slavery as a system advantageous to the slave.

On Sept. 18, 1896, The Asheville Daily Citizen reported on a meeting held by the Association of Southern Hospitals for the Insane. It took place inside the Battery Park Hotel. The article read: “One especially interesting feature was the discussion of the question ‘Has Emancipation Been Prejudicial to the Mental and Physical Health of the Negro?’”

According to the paper, findings presented at the meeting suggested freedom had in fact had an adverse effect on African-Americans, especially former male slaves. The article went on to include the opinions of several doctors present at the event. One suggested that before emancipation, the slave “had as a rule been well treated. His master compelled him to remain in at night, he did not frequent the saloon, and at night he was well housed.” Another claimed that “during the period of servitude the negro was really more profitted than the slave owners.”

The Lost Cause narrative would spread beyond the perimeters of the South. On June 3, 1901, The Asheville Daily Citizen included the transcription of a speech by Capt. Richmond Pearson Hobson of Alabama. The oration took place in Detroit at a ceremony honoring deceased federal soldiers. (“Another sign of the changes time has wrought,” the paper declared.) Within his speech, Hobson proclaimed:

“I believe that slavery as it had existed from the foundation of our nation was a part of divine providence to redeem a portion of the benighted races of Africa. How else would natives have ever been brought over? How else even if such a thing as voluntary immigration could have taken place, could the unhappy emigrants have taken care of themselves when found adrift in a new continent? How could they in such a condition have been brought under the uplifting influences of a higher civilization? There is no answer except that slavery was for these reasons necessary. And, my friends, believe me, for I have seen the old darkeys and have listened to their accounts of the times before war, that on the whole the condition of slavery with the highly cultured people of the south was indeed a beneficial one. Thus instead of the fact of slavery being a blot I consider it in all its elements a credit to the south.”

Exactly 10 years later, on June 3, 1911, The Asheville Gazette-News reported the local Memorial Day speech delivered by a Rev. Saumenig. The article’s headline read, “Defeat of South not a Lost Cause.” Early on in his talk, Saumenig bemoaned his own absence from battle, stating:

“It was my misfortune not to have been born in time to share the privations of those of my friends and brethren who manfully, honestly and bravely and with righteous, holy and well defined purpose fought under the flag of the Confederacy.”

Near the end of his speech, Saumenig addressed the duty of all Southerners moving forward:

“It is the bounden duty of the southerner, the profound obligation imposed upon the Daughters of the Confederacy, as an organization, to employ every honorable means within their power to see that the text books of history used in our public schools shall be those giving the facts and truths about the cause and the war of ‘61-’65.”

Five years later, author Daniel Harvey Hill would publish his 1916 textbook, Young People’s History of North Carolina. In addressing the question of slavery and its role leading up to in the Civil War, Hill wrote:

“The Abolition party of the North was growing stronger each year, and was by its pushing zeal keeping the nation stirred to its depths. Already many Southerners, feeling that the Constitution was being violated, were declaring the need of withdrawal from the Union.”

Later in the textbook, Hill claimed relations between former slaves and ex-Confederates would have remained peaceful had it not been for the introduction of federal agencies in the South during Reconstruction. He wrote: “If they and their former owners had been left alone in the State, each race would soon have been helpful to the other.”

Decades later, in the 1942 textbook, The Story of Our State: North Carolina, author W.C. Allen posed the following question to the book’s young readers: “Was slavery good or bad?”

Allen answered:

“Sometimes masters were cruel and treated their slaves brutally, but that was unusual. … It was greatly to the interest of slave owners to take good care of their slaves so that they would bring a good price when sold. Besides, the majority of slave owners in the South were good men and treated their slaves kindly, almost like members of their own families.

Some time you will read ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ a novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe, about slavery times, and you may get a different idea about how slave owners in the South treated their slaves. Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in the North and got the idea that our forefathers were cruel to their slaves. But the people who lived among us know that masters, with very few exceptions, were kind to their slaves.”

Peculiarities of spelling and punctuation as well as antiquated and offensive language are preserved from the original documents.

I am not certain, but I think you are mistaken in your description of Richmond Pearson Hobson as a former Confederate officer – unless there was another prominent man of the same name hailing from Alabama during that era.

Hobson was born in 1870 in Alabama, son of Sarah and James Hobson – and nephew of the Honorable Richmond Pearson of North Carolina. He graduated from the USNA in 1889.

He was a hero of the Spanish-American War, responsible for the failed attempt to scuttle the retired collier USS Merrimac, at the entrance to Santiago Bay, and he received the Medal of Honor for this action. He left the Navy around 1903 at the rank of Captain.

After his naval service he entered politics and became the Democratic US Representative from Alabama – he was a supporter of women’s suffrage and prohibition. He was promoted to the rank of Rear Admiral (two star) by special act of Congress in 1934 and died in 1937. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9155/richmond-pearson-hobson

Hello Phillip,

Thank you. I double-checked the newspaper article. Indeed, I mistook his title. I’ve made the correction for the online version. The quote offered by Hobson, however, is true to the June 3, 1901 publication.

Always good to hear from you.

I didn’t dispute the quote. Only the identity of the man…..I am sure that his quote reflected the sentiments of most of the South – and a good part of the North – at that time.

I didn’t mean to suggest you did. I bungled Hobson’s title. I wanted to assure you and other readers that was the extent of it.

Thanks – I didn’t think that was what you meant – but no telling what interpretation certain of the other readers might have!

I would also add that several occurrences around the time of the Spanish-American War did much to reunite the Nation and bring about a nationwide appreciation of the courage of former Confederate Soldiers (the death of President James Garfield, a former Union general who was popular in the North and South, brought much of the country together in mourning in 1881).

General Fitzhugh Lee (nephew of General Robert E. Lee) was serving as the US Consul General in Havana when the USS Maine exploded. His conduct as the first US government official to deal with the tragedy gained him the admiration of the nation. Lee and 3 other former Confederate generals were appointed by President McKinley as Major Generals of US Volunteers. The most prominent of these was General Joseph “Fightin’ Joe” Wheeler, CSA, who was serving as a Congressman from Alabama when the War broke out, became a combatant commander in Cuba.

General Wheeler was a small man – not much over 5 feet tall, and several reports of his actions under fire in Cuba captured the National imagination – even Tin Pan Alley cranked out a tune in his honor called “He Laid Away His Coat of Gray to Wear the Union Blue” – Wheeler went on to receive a commission as a Brigadier General in the US Regular Army after the War – the only former Confederate general to do so.

Some scholars think that President McKinley’s decision to bring on some old Confederates in high-visibility roles in Cuba did more to heal the rift between North and South than anything else to that point. Some of the romanticism regarding the Confederacy was brought about not so much by white supremacists seeking to re-establish themselves (although was part of it), as it was due to the desire of Americans to heal the Nation. Other evidences of this were the sympathetic treatment of the South in popular literature and early movies – and the naming of military bases located in the South after Southern leaders – as I write, I am sitting between J.E.B. Stuart Avenue and Pleasonton Rd – respectively named after Confederate and Union cavalry generals.

My point is that some – not all, but some – of what is seen as the “Lost Cause Narrative” today came about largely due to the National movement for reunification of the North and South – and the aging and passing of the GAR and Confederate veterans as the years went on – especially when things like the 50 year and 75 year Blue and Gray Reunions at Gettysburg in 1913 and 1938 were recorded on motion pictures. There was much more to the whole thing than white supremacists trying to make in-your-face gestures towards blacks and Yankees.

National reunification was part of it, I agree. How that reunification came about, and at whose expense, is part of the overall narrative, as well.

Thus it has been many times down thru our history and world history – the advances, recoveries, discoveries, progress, etc., of one Nation, race, or group always came at the expense of someone or something else. Very few things that have benefited everyone equally – or at all…

That’s a very fuzzy way to admit that many American policies ostensibly guided by principles of national unity just happened to exclude the same groups of someones.

If we can all agree, at a bare minimum, that a non-negligible part of the reason for Confederate statues was to promote a Lost Cause narrative mired in white supremacy, then it should be a simple matter to take that part of the statue (and whatever might come attached) and remove it to a less obnoxious location. The most significant public spaces would then be freed up for better (though not necessarily perfect) uses, including statues of heroes who bring a bit less baggage to the platform. Whatever “benefit” people might have once seen in prematurely ending Reconstruction and promoting a national reconciliation on the backs of African Americans, we have ceased to cherish it so much today. At least I have. To keep Confederate statues where they are, therefore, produces little good, preserves bad ideas, imposes unnecessary social costs, and squanders huge opportunity benefits. At some point, even the most radical Southern partisans must put aside ideology and learn to be fiscally responsible.

I suppose I should say “to keep all Confederate statues where they are.” Some might be okay — say, in a battlefield context or something like that.