Carl Petzold leans over a large stainless steel vat, watching its contents slowly circulate. It’s a humid afternoon, and he removes his hat, wipes sweat from his graying brow and brushes away a fly.

Like the rest of Petzold’s equipment, the former dairy vat has been repurposed to its current use. And in about a week, the swirling liquid it holds will become the newest flavor of Carl’s Carolina Spirits: peach moonshine.

While explaining the ratio of sugar to peaches, Petzold languidly reaches over to flick a June beetle from the froth collecting on top. “An old-timer told me once, ‘Son, if the bugs don’t come to it, don’t drink it,’” he says, grinning conspiratorially.

Petzold is one of a growing number of Western North Carolina craft distillers making legal moonshine. Blending traditional recipes with new technology and methods, these pioneers are bringing Appalachia’s most fabled and misunderstood product into the 21st century, changing cultural perceptions even as they adapt to shifting economic realities.

History of hooch

Variously known as white lightning, mountain dew and moonshine, white liquor is an integral thread in the American tapestry. With origins in early-19th-century Scots-Irish communities, ’shine was an important economic, cultural and political driver of antebellum Appalachia.

“Consumption of alcohol had a prominent place in the life and culture of the region,” Daniel S. Pierce writes in Corn From a Jar. Throughout the mountains, moonshine played a pivotal role in everything from elections to herbal remedies.

Conflict between governing bodies and bootleggers stretches back equally far. A 1791 federal excise tax on distilled spirits triggered the Whiskey Rebellion, as frontier farmers resisted government efforts to collect the tax. It was repealed in 1801, but in 1862, Congress passed a federal excise tax that still stands today, sparking the beginning of the “moonshine wars” in southern Appalachia.

Prohibition, in effect in North Carolina from 1909 to 1935, drove the market value of liquor through the roof. And the continuing cat-and-mouse game between federal agents and bootleggers produced characters and institutions that have become central to American life.

High-speed chases down narrow mountain roads evolved into NASCAR, as many early rumrunners transferred their talents to the racetrack. Larger-than-life figures like Quill Rose and Lewis Redmond helped mythologize the moonshiner, spawning countless dime novels based on their exploits.

Moonshine goes mainstream

By 2000, however, ’shine had mostly faded from the popular imagination, due to increased job opportunities in the southern Appalachians and the rising cost of ingredients. NASCAR had distanced itself from its boozy beginnings, and holdovers like Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton were known more for their personalities than their brewing prowess.

But a subsequent enthusiasm for craft brewing, and a loosened federal permitting process, piqued interest in the time-honored tradition. A new generation of students, entrepreneurs and self-described “rednecks” began seeing market potential in bringing back ’shine.

For Petzold, the path to white liquor began at the gas pump. “I originally started out making fuel alcohol” in response to a 2010 regional gas shortage, he reveals. Encouraged by friends and business associates, Petzold crossed over to moonshine two years later. “The process for making moonshine and making fuel is somewhat similar,” he notes. “I was able to switch pretty easily.”

Cody Bradford of Howling Moon Distillery says a combination of fiscal necessity and family history led him to try his hand at the still. “When the economy wasn’t doing so hot, me and a friend decided to start our own business and figured that liquor sells, even in a bad economy. Part of one of my stills,” he continues, “is my great-great-grandfather’s; we use an old family recipe.”

Asheville Distilling Co. founder Troy Ball was intrigued by the old moonshiners she met, who she says were producing a “nice, smooth, white whiskey. Why are we drinking Russian cocktails,” she wondered, “when we could be drinking American?”

Ball’s distillery, which opened in 2011, has achieved wide distribution. “We’re at Disney World and all the resorts there,” she notes. “We’re also at high-profile restaurants in Charleston, South Beach and, soon, Brooklyn. Brooklyn loves whiskey.”

Phases of production

“Practically anyone can make liquor, but it takes talent to make good liquor,” writes Pierce, a UNC Asheville history professor.

Ball’s operation uses heirloom white corn, grown and ground at Peaceful Valley Farm near Old Fort. “Having the incredibly rare Crooked Creek Corn was important to our recipe,” she says. “In the 1800s, if you lived in the mountains in Appalachia, you would be growing white corn and making whiskey from it.”

Asheville Distilling, notes Ball, also sacrifices volume for quality’s sake. “We don’t even use 100 percent of the distillate like most people do: only the heart of the distillation, instead of 99 percent of it and giving everyone a headache.”

Petzold, too, relies on an old family connection, buying his fruits from Henderson Farms in Flat Rock. Local produce, though, is only the beginning: His whole handcrafted setup consists of items originally used for something else.

“I believe I have the only wood-fired, steam-jacketed kettle in the entire country,” he says, pointing to a repurposed furnace welded to an old wood stove. Petzold harvests firewood from his property and water from local sources, builds his own filters and hand-bottles his product. “We live by the rule of keeping things simple,” he explains.

Howling Moon, too, sticks to time-honored practices. “We make it with a traditional still with a pot, a front keg and a ‘worm,’ or condenser,” says Bradford. And if modern technology is more efficient, he maintains that his approach yields a product “that anyone who’s ever had real moonshine will recognize.”

From holler to Hollywood

Moonshine’s renaissance is reflected in television shows like the Discovery Channel’s “Moonshiners” series, which presents a somewhat glorified version of the craft. Films like 2012’s Lawless also deal with Prohibition, bootlegging and the struggle between lawmen and mountain folk.

“A lot of it is nostalgia,” says Pierce, citing the media savvy of 20th-century ’shiners like Sutton. “Popcorn’s genius was in promoting, and in marketing his own image. He really led the revival.” In his later years, Sutton regaled the public with tales of his ’shine exploits in an autobiography and several documentaries.

That example has some local entrepreneurs considering how they, too, can capitalize on moonshine’s popularity. Georgia Malki, co-founder of Asheville’s Lex 18 moonshine bar, believes white liquor allows for innovation in ways that other spirits don’t.

“When something comes from a steep tradition, like whiskey or Scotch, the things that help provide it with stature are the very things that limit it,” she points out. “But there’s nothing like that around moonshine. It’s old but has no legal expectation: It’s the ultimate American spirit.”

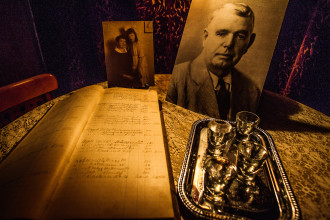

In creating Lex 18, Malki and her design team, Jack & Masters, have drawn on the property’s history as one of Asheville’s most notorious speak-easies. “We thought, ‘Isn’t it interesting that we’re in moonshine country and nobody’s doing moonshine'” as a theme, she says. “Here’s a building that served not only as a bar but later as a speak-easy, owned by a very innovative saloonkeeper and businessman, John O’Donnell. It doesn’t take a lot to put two and two together and decide that this is perfect for restoration.”

The Eureka Saloon, which operated on the same site from 1904-1933, featured trapdoors and a secret tunnel under Lexington Avenue and College Street, so bootleggers could discreetly transport product to neighboring businesses. Malki has some of Eureka’s old ledgers, which give clues to how O’Donnell masked his illicit trade. “He was cooking the books,” she explains. “He’s showing that what he’s buying is milk and some laundry and ice — to generate, in 1907, $283 a day using $2 worth of materials.”

Malki believes Asheville’s historical association with moonshine gives the area an advantage. “We shouldn’t let the Piedmont try to take the spotlight on moonshine. We’re in the mountains: We sit in the center of everything that was happening regionally.”

Ball, though, is quick to temper get-rich-quick dreams. “Everyone thinks they’re going to become overnight billionaires, which they’re not. It’s a costly thing to build a brand.”

Meanwhile, a recent market downturn is slowing growth. “Right now, it’s really on the decline,” Petzold reports. “If you look at the state’s numbers, yes, moonshine is selling. But if you look at the total revenue it produces and divide that by the number of distillers, it’s getting harder and harder for us to sell.”

That downturn is partly due to a flood of new brands that vary in quality. “There are some substandard products being put out with the good products, and people get turned off,” says Petzold. “There’s big-name products out there that don’t even distill. It’s a farce.” Instead, he says, they simply dilute neutral grain spirits with water and add flavoring.

Competition among craft distillers is generally friendly but fierce, as more and more operations vie for sales in a limited market. “Do I hate them? Yes, I hate them,” says Petzold, his tone somewhere between wry humor and bemused sincerity. “I just want to strangle them all, because a lot of them started with money. They didn’t have their nose to the grindstone.”

Pay to play

One major difference between illicit moonshiners and their legal counterparts is the latter’s willingness to comply with federal and state liquor laws. “It’s called excise tax,” says Petzold, “and that sh*t has got to be paid.”

Setting up shop is time-consuming and expensive, notes Bradford. “It took us about two years just to get our permit. They want to tax every single part of it: everything you buy, everything you make or dump out.”

Distillers selling domestically must pay federal taxes within 15 days of a sale. And while rates vary depending on the product, a 750-milliliter jar of moonshine racks up about $2.14 in taxes, compared with less than $1 per bottle for beer and wine, according to the U.S. Treasury Department’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

North Carolina also oversees and regulates the distribution and sale of liquor through the state Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission and localized ABC boards.

Created in 1937, the commission is “the chief regulator of all alcoholic beverages in the state,” says Public Affairs Director Agnes Stevens. Responsible for warehousing, documenting and distributing liquor to 423 ABC retail stores, the agency also collects taxes and fees and determines which products can be sold in the state, and how.

The regulatory body works closely with local law enforcement agencies and the state’s Alcohol Law Enforcement branch to enforce liquor provisions. Distillers must apply for both federal and state permits before manufacturing begins, and the commission, notes Stevens, doesn’t issue a permit until federal officials have approved both the product and the label. The distillery is then entered into the state system, and its products are assigned specific codes for tracking sales and distribution.

Distillers, says Petzold, are notified electronically whenever a sale is made, helping them track their products. ABC stores must pay the distiller within 30 days of placing an order. “I set the shelf price,” he explains, “and then they deduct the state’s taxes, bailment charges and other fees, and we get the rest.”

Most local distillers seem to feel that the taxes are manageable and that the commission isn’t difficult to work with, though some question certain facets of the regulatory body’s operating methods. “It’s a complicated process, and it’s highly regulated and taxed,” says Bradford.

And Malki says that while she understands the need for health and safety requirements, other aspects of the law need revisiting. “To suggest that we want to discourage people from drinking is silly. That’s a moral judgment and really shouldn’t be decided by the state.”

Meanwhile, changes to state liquor laws last month have loosened restrictions on distillers selling directly to consumers. Distillers in areas with at least one ABC store are now allowed to sell each visitor one “commemorative” bottle per year.

In the current economic environment, says Stevens, “The challenge is for distillers to differentiate themselves in an increasingly crowded market.”

Malki agrees, saying the overall success of the industry depends on how well distillers understand this. “Right now, vodka stands as the No. 1 spirit in the U.S., because bartenders found it to be one of the most versatile ingredients to produce a range of different cocktails for customers.” But she believes that moonshine, with its “extraordinary versatility and more traditional skews and profiles of flavors,” can eventually claim that crown.

For his part, Petzold sees product diversity as “security for the house. It helps keep the lights on.”

Dark side of the moon

Amid the excitement surrounding these legal operations, it’s easy to forget that there are still many small-time ’shiners distilling in the shadows. One such native resident, who declined to be named, describes his operation as “pretty small — a couple gallons a batch. We got what’s called a silver still; it’s galvanized to prevent corrosion.” And most of those who choose to carry on their business beyond the reach of Uncle Sam, he continues, “are working the same recipes they have for generations, whether it’s a family tradition or learned from a friend.”

Lex 18 doesn’t sell illegal products, but Malki believes outlaw ’shiners are an important facet of mountain heritage. “We really have to guard against creating a corporate structure for everything that happens in our country,” she maintains. “Whether it’s a hobby or selling to neighbors, [moonshine’s] an important part of the American tradition, and certain things in life shouldn’t be dictated by somebody’s idea of legitimate business.”

But with legal alternatives now available and homemade hooch’s market value drastically reduced, old-fashioned ’shiners find themselves in a peculiar situation.

“It’s very challenging when your family’s been doing it for a long time,” says Malki, “and now anyone can walk into an ABC store and get a fancy bottle of moonshine in all kinds of colors and flavors. Where does that leave you?”

Some have branched out into more lucrative (and dangerous) trades. “The profit margins on growing marijuana or making methamphetamine are a lot greater than those of moonshining,” notes Pierce. “When they have a moonshine bust these days, the folks are often caught with meth or marijuana, too.”

He also cautions consumers about purchasing illegally made liquor. “You don’t know if it’s been run through a car radiator or what’s been added to it.”

Bradford concurs. “You have a lot of younger people jumping on the bandwagon and saying they’re ‘moonshiners’ who know nothing about it.” Improper production practices, he notes, can lead to things like copper poisoning or exposure to methane, a byproduct of distillation. “A lot of the old-timers who make it were taught by their family; they know the dangers and secrets and [process]. If you just saw it on TV and bought a still and try to make it, you can kill somebody,” adds Bradford.

And beneath the romantic veneer surrounding moonshine and its makers, violence still lurks.

In March 2013, Calup Joe Caston was found near a boat ramp outside Bryson City, severely beaten and stabbed through the back with a samurai sword. Rushed to Mission Hospital, Caston was pronounced dead on arrival. Investigators pinned the attack on members of the Savage Anarchy Knights, a local moonshining gang; within days, eight men were arrested. According to a WLOS report, the Knights suspected Caston of having spoken to authorities about their activities.

Charged with first-degree murder, kidnapping and robbery with a deadly weapon, alleged gang leader Joshua Price recently copped a plea. He’ll avoid the death penalty, but the 22-year-old will spend the rest of his life in prison without parole. The remaining defendants are awaiting trial.

Good moon rising

Squatting at the entrance to Petzold’s distillery in Shelton Laurel, we watch intermittent rain clouds crest the ridgelines. I ask about the upcoming distillery tours, organized by the state to ferry visitors around the region for a peek into local operations.

“I wasn’t quite prepared for this year, but they talked me into it,” he reveals, gesturing at half-finished insulation and construction debris — signs of a business built from the ground up.

Petzold wants to add another building to house the bottling equipment, and there are plans for a merchandise area where, under the new laws, visitors can buy a jar of his product and perhaps a hat or T-shirt.

Meanwhile, he’s excited about the new batch of peach ’shine. Other flavors are also in the works, though Petzold isn’t ready to share details yet. As with every other facet of his operation, he’s prefers to take it slow.

“The pace that I’m setting is really going to get us back to the production level where I cannot do it by myself,” he muses. Petzold used to go to conventions and shows, actively marketing the product. But family concerns and a fluctuating market made him reconsider. “I said, ‘You know what, Carl? You’re putting food on the table. Don’t rush.'”

Petzold plans to start making his own barrels, and he hopes to grow sugar cane and eventually produce molasses and raw sugar, cutting operating costs while creating additional products. Like any mountain man worth his salt, he knows that the more things you produce yourself, the less you have to depend on others. He’s also thinking about his children.

“This is all really for them,” says Petzold. “I want to leave this whole thing at a point where my kids can take over, and I can sit back and get out of the way.”

Taking a pinch of Copenhagen tobacco, he stares into the distance. “Maybe then I’ll have some time to get back to fishing. Or go bear hunting again.”

And maybe, eventually, the Carl Petzolds of the world will fade into the background, joining prior generations of innovators and outlaws, businessmen and farmers who’ve roamed and chased one another across these mountains, like children after fireflies, trying to catch “white lightning” in a jar.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.