At PEAK Academy during a recent school day, a student was repeatedly speaking out of turn in class, intentionally disrupting the learning process for other students. A teacher stepped out to walk with him down the hall, acknowledging his frustrations rather than blaming him for feeling upset. A little break from the classroom may be all he needed, the teacher offered.

They were on their way to what PEAK administrators call a “reset room” — a place students who may be feeling overwhelmed, inadequate or downright indignant can go to assess their emotions and reset until they are in a place where learning is once again possible. In many instances, this is used in lieu of traditional discipline, when a student might otherwise earn a write-up or trip to the principal’s office for repeatedly speaking out of turn or belittling his classmates.

This technique is one example of how the third-year Asheville public charter school, whose student body is majority Black, has begun to successfully close an achievement gap between white and Black students that has consistently been an issue in Asheville City Schools since it earned a worst-in-the-state designation in 2017.

The school was born after Black community leaders’ frustrations with continued failures by a revolving door of ACS superintendents — there had been four in six years at that point — to successfully address the issue boiled over in 2019, says Dwight Mullen, a retired professor of political science at UNC Asheville who serves on the board of PEAK Academy.

“Each one of them had been hired to address and close the disparities by race. And none of them were successful — none of them. So that led to the charter school approach,” he says.

The result was PEAK Academy, a public charter school started in 2021 in a building owned by Trinity United Methodist Church in West Asheville. PEAK’s executive director, Kidada Wynn, says the mostly Black staff and faculty have created a space where Black students feel accepted, respected and loved in a way that allows them to focus on learning rather than worrying about when they might be disciplined next. The charter also assures that students’ families incur no expenses for sending their children there.

PEAK — an acronym that stands for Prepare and Empower students to Achieve excellence and obtain Knowledge — started with kindergarten through third grade and added fourth and fifth grades this school year. Per its charter, it will add at least one grade per year up to eighth grade. Currently, 176 students are enrolled.

Feeling safe

The reset room, which Wynn brought to PEAK when she arrived in November 2022, is one of many techniques administrators say they use to show students that they are safe at school. They say Black students in particular reported feeling afraid of constantly getting in trouble or suspended at traditional public schools before they came to PEAK, making it hard to focus on learning.

That is reflected in data collected by the Youth Justice Project, an arm of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, showing that Black students in ACS were almost 12 times as likely as white students to receive a short-term suspension in 2021-22, the most recent school year for which the project had data.

Camesha Minto, PEAK’s director of curriculum instruction and testing, says when students express despair and frustration, teachers at PEAK get down to the students’ level rather than sending them down a disciplinary track.

“We try our very best to ensure that we are extending that patience, that grace. And we’re also giving our kiddos that ear to kind of listen to what it is that they’re saying, understand where they’re coming from and also use that background knowledge that we have of, ‘Oh, my goodness, this little kiddo might not have had breakfast this morning. This little kiddo might not have had a good night’s sleep last night.’ We can empathize with that and be like, ‘OK, take a minute if you need to, but you are going to do this. Because it’s not that we can’t, it’s just that we can’t yet.’”

Keeping students in classrooms is just part of an approach that has led to better scores for Black students in grade-level proficiency in math and reading than all schools in the Asheville City Schools district in the 2022-23 school year. Peak Academic Bar Chart

Districtwide, Asheville City Schools’s achievement gap hasn’t improved since 2015-16, when it was the largest of any of the state’s 114 districts, according to data from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

“Addressing the long-standing achievement gap within ACS is one of my top priorities,” says ACS Superintendent Maggie Fehrman. “I completely understand the frustration of Black leaders in our community. We know that a strong sense of belonging is one of the foundational elements that needs to be in place for each student to achieve their full potential, and I am committed to ensuring that happens. We are about to undergo a comprehensive strategic planning process focusing on identifying innovative and proven practices to address the disproportionate outcomes in ACS.”

Just 14% of Black students achieved grade-level proficiency in math and reading for grades 3-8 in ACS in 2022-23 compared with 74% of white students. In 2016-17, those numbers were 23% and 83% for Black and white students in ACS, respectively.

While there is still a large gap of 38 points in Buncombe County Schools, it mirrors state averages.

Although some assume charter schools scrape the cream off the top of public schools’ student body, part of PEAK’s mission is to serve the most economically disadvantaged students in the community. Iesha Gilliam, PEAK’s director of student services, notes that about 72% of its 176 students live in public housing.

PEAK focuses its recruiting efforts in those lower-income neighborhoods, although it is open to anyone who wishes to attend. Its student body is majority Black, Gilliam says, because those are the students most interested in attending a school geared toward closing the racial achievement gap.

And the school is doing just that. In just its second year open, about 54% of Black students at PEAK achieve grade-level proficiency.

Wynn says in addition to inventive disciplinary tools, another reason PEAK’s students are showing improvement is her successful recruitment of highly educated Black faculty.

“Those two things together — [experienced Black staff and tools such as reset rooms] — have been what has changed the trajectory of our students’ academic and social careers and lives,” she says.

Educators of color

Every teacher at PEAK has a master’s degree and at least 11 years of experience, Wynn says.

Crystal MacKinnon, a board member for PEAK Academy, is quick to highlight that difference for PEAK as opposed to other charter schools. In North Carolina, charter schools have more lenient rules than traditional public schools when it comes to teacher certifications, but PEAK goes above and beyond those requirements, MacKinnon says.

“We don’t follow the paradigm of a typical charter school in almost any way,” she says, noting that the school provides transportation, meals and uniforms to students free of charge.

Like a traditional public school, PEAK receives state funding based on its average daily membership, or attendance. Last year, the schools received about $7,300 per student, according to the NCDPI. Unlike traditional public schools, charter schools do not receive additional local funding to supplement their staff pay and cannot request an additional tax levy like Asheville City Schools.

That leaves it to fundraise more than $1.2 million from private donations and local grants this year alone to match the school’s $2.57 million budget, MacKinnon says.

Beyond experience, a major factor of PEAK’s teacher’s success is their background, says Minto, a teaching veteran of 21 years who is originally from Jamaica.

“I think what we do differently here as a school is that we have teachers who actually look like the kids we serve. OK, so these kids can see someone who is here to teach them, to inspire them, who looks just like them,” says Minto, who taught in Wake County, home to Raleigh, before joining PEAK in 2021.

At ACS, according to the Youth Justice Project data, representation is another shortcoming. In 2021-22, 7% of its teachers were Black, compared with 19% of its student body. At BCS, just 1% of its teachers were Black that year, compared with 7% of its student body. And at PEAK, 85% of its teachers and 92% of its staff are Black, compared with about 74% of its student body. Another 12% of its students identify as multiracial.

“I believe, when you’re a person of color, there are certain things that you’re able to understand [about] kids of color than if you are someone who is Caucasian. Sometimes you don’t, you really don’t get it, because your experience is not there. So, for us here at PEAK, we can identify with our scholars, where they’re coming from, their background and what they need,” Minto says.

That approach works best when teachers look like their students, but Minto says the most important thing is meeting students where they are.

“I’m an educator. So, when I look at kids, even here at PEAK, we have kids who don’t look like me, those kids are welcome just like every other kid.”

Michael Hayes, founder and executive director of Umoja Health, Wellness and Justice Collective, a nonprofit serving trauma-affected youths through the arts, has two students at PEAK.

His fifth grader just transferred into PEAK because “he needed to be around a more culturally specific group of people in order to thrive,” Hayes says.

Shared experiences between teachers and students can help in the reset rooms as well, Wynn argues, because when you see someone you love and respect within your teacher, you are more likely to show them respect back.

“They just have a level of understanding and no judgment. It’s a no-judgment zone. And so, our students feel safe, and they feel heard, and they feel confident that they can stand in whatever decision they make. And they can ask for help. And they can be OK with making a mistake. All while our standards are very, very high,” Wynn says.

High standards

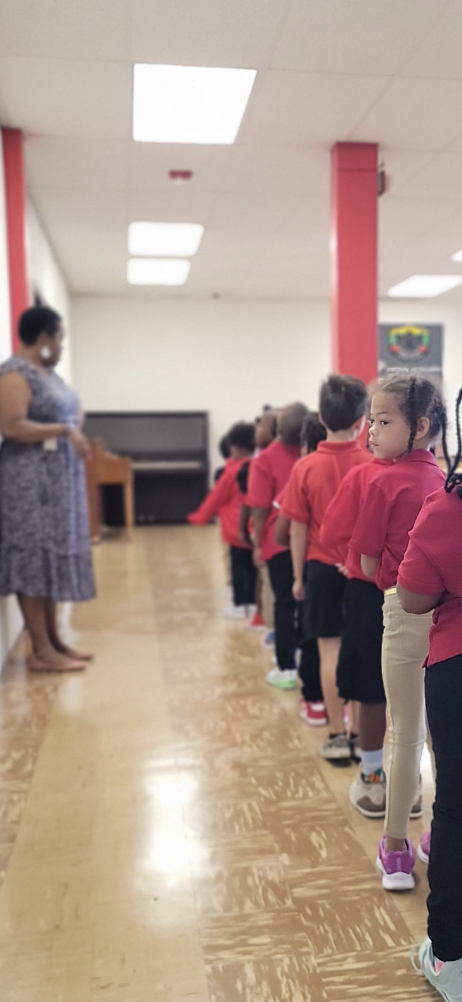

Those standards are clear from the moment you walk into PEAK, where students are called scholars — not students, or kids — by every adult in the building.

Wynn says she implemented that language as a way to combat her own experience as a student graduate of ACS as well as an employee, where the minimum was expected of her.

“That’s all they expected out of me. And so, when I would offer more, they didn’t know if it would work,” she says. “I’m taking my lived experience and making it what I wish it would have been here at PEAK.”

Those higher expectations, along with teachers that look like the student body and a more restorative approach to discipline, is what Wynn says truly sets PEAK apart.

“We don’t expect you to walk out of class, misbehave and do what you want to do so we can call [your parents] and send you home. We don’t do that. So, the expectation is that when it’s time to learn that you’re learning, when it’s time to play that you play.”

Minto, who manages testing at PEAK, sees greater deficiencies in the students who are transferring in later from other schools than those who started at PEAK in 2021-22.

“So those kiddos are already coming in at a disadvantage, which is the reason why testing is so important for us to understand where they are and what we need to do. Because we’re expecting them to grow two to three grade levels within that one year [to catch up],” she says.

Students who graduate from PEAK will head back to public schools, most likely Asheville High School and ACS.

Minto plans to have them on grade level and ready for that transition, she says.

Hope for the future

Everyone from the PEAK universe who spoke to Xpress for this story expressed determination for its success. But there are challenges, most prominently space and financing, says Mullen, the founding board member.

“This is a crude way of thinking about it, but … the last time I saw the median income for a Black family it was under $40,000 a year. And we are a school that has a budget of over $2 million a year. So those two don’t match,” says Mullen.

That leaves administrators to fundraise, search for grants, and survive in their small building at Trinity United Methodist Church, where the school is bursting at the seams with three more grades yet to be added.

“It’s hard to keep the doors open and depend so much on private donations and sponsors and stuff because they get donor fatigue,” Wynn says.

Regardless of financing, Mullen acknowledges the future success of the school — and its current and future scholars — relies in part on its relationship with the school districts around it.

Looking at the bigger picture, Mullen is trying to build a community of educational institutions, not just one school that closes the gap.

“If we really, truly want what is best for every scholar, then we would do whatever we could do to make it happen. We would have a healthy school system. It’d be a no-judgment zone,” Wynn says.

“We wouldn’t have to be like crabs in a barrel. We’d have shared resources across the city of Asheville. To help every scholar reach their fullest potential, no matter what they look like, where they come from. They could be their best selves, and we’d make sure of it. And the expectation would be that we hold each other accountable to do so in every building across the city,” she says.

To do that, relationships across schools and districts are necessary, and Mullen and Wynn hold out hope that their vision is attainable. ACS Superintendent Fehrman and Asheville City Board of Education Chair George Sieburg, for example, have toured PEAK Academy to see what strategies could be duplicated.

Fehrman says she had an amazing experience on her PEAK tour.

“I saw highly engaged students in every classroom learning on grade level or above. I am eager to partner with PEAK and learn from their successes,” she says.

“I think it’s real. I think that [Fehrman’s] taking it very seriously. I’ve had personal conversations [with Fehrman and Sieburg], and they are very much on the same wavelength of being in harmony with us [working] as partners in closing the disparity gap,” Mullen says.

Great article. The mission, intentional method, and stated success measures at PEAK are impressive. Unfortunately, since the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – regardless of merit or intent – it is not legal to frame education on the basis of color – any color. Efforts are being made all over our community in education and governance to right racial wrongs with more racial wrongs. One understands the sympathy, but attempting to circumvent 1964’s hard-won effort to take color out of our national equation is neither prudent nor legal. The author has made a clear effort to share a positive take on the good mission of PEAK. Ignoring their leadership’s public declaration of a dedication to the use of racial quotas for student and faculty as an imagined license in their charter is a remarkable oversight by a publication that is well informed on this fatal institutional flaw. Reconsideration of the use of discrimination to address the echoes of discrimination should be on the minds of anyone wishing to support PEAK’s forward success. [ rey-siz-uhm ] noun – Discrimination or prejudice based on color…

But but but that’s not what they want now! Integration be damned. ‘More culturally specific’ … is that racist ?

Perhaps the parents of these students emphasize the importance of education, insist on finished homework, show up for parent nights, and engage with the teachers for the good of everyone. Perhaps most black students don’t have such parents, and therein lies the poor level of outcomes. Not everything is the fault of white people. Why on earth have we not figured that out by now?