By Liz Carey

When you think about the Great Smoky Mountains, you might conjure grand vistas, verdant forests or majestic elk. Your thoughts might not immediately jump to death and destruction.

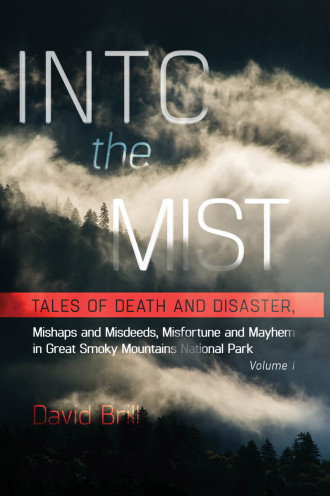

But that is exactly what adventure travel writer David Brill of Morgan County, Tenn., dives into with his new book, Into the Mist: Tales of Death and Disaster, Mishaps and Misdeeds, Misfortune and Mayhem in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

The book, published by the Great Smoky Mountains Association, explores all the fatalities that have occurred in the 83-year history of the park. Far from being simply a morbid litany, however, the book also magnifies the bravery and heroism of park rangers and visitors in times of stress and trauma.

The book, published by the Great Smoky Mountains Association, explores all the fatalities that have occurred in the 83-year history of the park. Far from being simply a morbid litany, however, the book also magnifies the bravery and heroism of park rangers and visitors in times of stress and trauma.

Great Smoky Mountains is the most popular national park in the United States, attracting more than 11 million visitors to its more than 800 square miles each year. Since its establishment on June 15, 1934, the park has become a vacation destination for Americans and tourists from across the globe.

The park gets its name from the mists and fogs that shroud the mountains. Those fogs, while beautiful, are among the inherent dangers that can turn the park from a peaceful recreation area to a potentially life-threatening environment.

Dangers abound

Into the Mist looks at factors that can turn the land from relaxing to relentless — factors such as trees falling, horses bucking and lightning striking.

“The last thing I wanted to do is make people fear this amazing natural resource, but I do want them to respect what can happen in the park if you’re not prepared or don’t take it seriously,” Brill says. “People are so afraid of bears and snakes in the park, but the real danger is auto accidents.”

In fact, Brill says the top two causes of death in the park are automobile accidents and airplane crashes. Other top causes include heart attacks, falls, drowning, lightning strikes, hypothermia and suicide. There has only been one fatal bear attack in the park’s history and no recordings of fatal snakebites, but there have been 14 reported murders.

Chapters look at the varied causes of death in the park by focusing on specific stories that illuminate the dangers of different elements of the park — whether created by nature or by man. For instance, the book details an epic snowstorm in March 1993 that left rangers struggling to rescue some 150 people, including 80 prep school students and faculty. It tells of a suspected murderer ready to kill any park rangers who got in his way. And it recounts a suicide pact gone wrong.

Brill says it took him two years to research and write the book, starting first with GSMNP ranger incident reports about the 468 deaths that occurred in the park between 1931 and 2013.

“Before I started picking and choosing what to write about, I wanted to get an overview of everything,” he says. “I was able to get information from the National Archives, from park headquarters. … It was a long process, but once I had read all of the incidents, I was able to file requests for specific incident reports.”

Prepare for the great outdoors

The idea for the book came from Steve Kemp, head of publications with the Great Smoky Mountains Association.

“People who grow up without much experience in the out-of-doors sometimes have unusual ideas about good ways to recreate in the Smokies. Like the people you see on the snow-covered Appalachian Trail in flip-flops or those dragging their oversized coolers into a backcountry campsite,” Kemp states in a release. “This book offers folks a dramatic preview of some of the adversity they may experience in the mountains if they fail to plan and prepare.”

Reading through the reports, Brill says, he immediately saw that many stories were compelling and told of more than just death and destruction; they told of immense bravery, hardwired courage and the human struggle to survive.

Brill says the stories also illuminate the inherent dangers of wild, open spaces.

One tale tells of John Mink, a 25-year-old graduate student from Indiana, whose three-day, two-night, 12-mile hike in 1984 ended up being the last excursion of his young life when he was surprised by an unexpected snowstorm. Mink made many right choices, but the few mistakes he did make would ultimately contribute to his death.

Park rangers were able to piece together Mink’s final hours using clues the young man inadvertently left behind as he struggled to overcome the mounting snow before succumbing to hypothermia.

“What I think comes through is that these rangers are so much more than park guides,” Brill says. “They are resource managers, protecting the visitors from themselves and sometimes from the park. These are people who are there to protect the park, but who also have tremendous bravery and compassion while they are rescuing people from dangerous situations or pulling bodies out of the park.”

Brill says the book is just the beginning of what may be multiple volumes on the park and its relationship with death and destruction. Volume two, he says, would most definitely look into the 2016 Gatlinburg wildfire that took 14 lives and destroyed homes of those working to protect the park and its visitors from danger.

“I think it could easily go to five volumes,” Kemp states. “There are almost unlimited stories of dramatic encounters between people and nature.”

Currently, Into the Mist is available on the GSMA’s website, avl.mx/445, and on Amazon.

This sounds like a great read, and I love the title. I suspect many will make better choices after reading real-life examples. I am a member of Haywood Co.’s Search and Rescue Team, and undoubtedly the people we help learn from their own experiences. To that effect, I even wrote a piece on my own personal blog, outlining what every hiker should do before going on a hike and what they should take. Education is the key to prevent fewer of these tragic stories. My own post was inspired by an incredibly time sensitive rescue we participated in this past January in Shining Rock Wilderness, and one of the hikers involved was kind enough to let me interview him and share what he learned from the experience: http://www.hopeandfeathertravels.com/2017/10/how-to-save-your-life-in-the-woods.html.

I was actually at Sugarland Visitation Center during the Blizzard of 93. I would be the one in the Hum-Vee running radio traffic for the Aircraft and Track Units. Talking about an adventure.