Suppose you’re trying to cross a busy intersection: Most of us simply approach the crosswalk, push the button and wait till the signal says it’s safe.

Now imagine what it would be like to tackle that same task from a wheelchair. What if the button is just out of reach? Or if there’s not enough space on the sidewalk to maneuver while you wait for the light to change?

Transportation planner and consultant Don Kostelec says such issues are too often a reality for people living with one or more disabilities as they attempt to navigate public spaces that weren’t designed with them in mind.

Kostelec, who served on Asheville’s Multimodal Transportation Commission from 2014-18, says he frequently found himself notifying city officials about sidewalks, curb ramps and other examples of public infrastructure that didn’t comply with the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

And while he now calls Boise, Idaho, home, Kostelec says a recent visit to Asheville revealed new issues with ADA compliance, this time in the just completed River Arts District Transportation Improvement Project. The multiyear, $54.6 million RADTIP connects local businesses, parks and neighborhoods along a series of roads and greenways flanking the French Broad River.

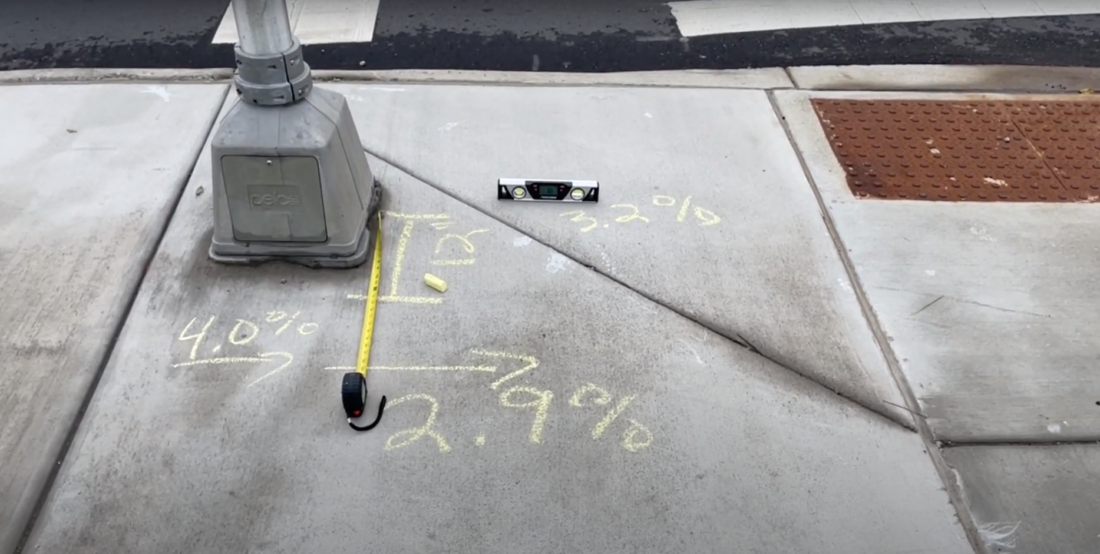

In a 14-minute video he shared with Xpress, the city of Asheville and other state and local leaders, Kostelec highlights issues such as sidewalk width, traffic signal timing and other failures to accommodate the needs of people who are vision-impaired, use wheelchairs or walkers, or are otherwise disabled.

“My grandmother is in a wheelchair and would not be able to experience the RADTIP sidewalk and pathway system without having her safety greatly compromised,” Kostelec wrote in a July 22 email to the city of Asheville. “I am saddened that people with disabilities in Asheville and those who visit the city will find their civil rights, freedom and safety compromised with this project.”

To Kostelec, these snafus in a brand-new major infrastructure makeover — and this despite his multiple attempts to draw attention to such problems in the past — underscore a broader pattern of city officials failing to address accessibility concerns for people with disabilities until or unless advocates point them out.

“These same issues that are here now on the city’s most marquee project are things their engineering leadership, the mayor, the city manager had been made aware of for many years, and no real action has been taken,” he maintains. “As much as Asheville talks about diversity and inclusion and it’s so much of their brand, why does this stuff get missed?”

Falling short

Capital projects director Jade Dundas says that even though the grand opening of the RADTIP was announced back in April with great fanfare, the city is aware of Kostelec’s concerns and is still working with design and inspection consultants to bring the project into compliance with the law. “There are several construction-related punch list items that still need to be addressed, including but not limited to what Mr. Kostelec observed,” Dundas told Xpress. “We have continuously partnered with the Federal Highway Administration throughout this project, and they are aware of the work that is being done to ensure that the project is ADA-compliant.”

But that catch-up approach doesn’t explain why such lapses keep happening, advocates say. At press time, the city had not responded to multiple requests for comment on those underlying concerns.

Nonetheless, Eva Reynolds of local nonprofit DisAbility Partners says that while she wasn’t aware of Kostelec’s specific concerns, she’s not surprised. In Asheville’s public spaces, Reynolds asserts, inaccessibility is “more common than not.”

Although the ADA prohibits discrimination — meaning cities can be federally fined or sued in class-action lawsuits if they fail to meet legal accessibility standards — it’s often left to people with disabilities or their advocates to point out where municipalities and private businesses fall short. What Asheville needs, she believes, is for local government to play a more proactive role in ensuring that public spaces are accessible to everyone.

“The letter of the law says you have to have an entranceway that’s 32 inches,” Reynolds points out. “The spirit of the law is to eliminate barriers that prevent inclusion, and this is where Asheville, I hate to say it, doesn’t do a very good job at all.” Topography, continues Reynolds, who is herself disabled, is part of the problem. “Let’s face it: We are where we are. But there are a lot of things we could do differently that would help facilitate inclusion of people in the community.”

Brad Stein, the city’s ADA coordinator, says that a planning process known as Close the GAP has begun soliciting input from residents about accessibility concerns as a first step toward updating the existing infrastructure in Asheville’s public spaces. Various departments, he says, are involved in the effort to develop an ADA transition plan for the city’s greenways and pedestrian areas.

“We’re engaging many community stakeholders to seek perspective,” Stein explains. “As a municipality, the city takes pride in delivering core services and ensuring that individuals across the city can access and benefit from city programs, services and facilities.”

Invisible in plain sight

For local artist Priya Ray, who is paralyzed from the waist down due to a 1999 spinal cord injury, ensuring accessibility goes beyond the nuts and bolts of infrastructure compliance: Ultimately,

she believes, it’s a question of culture, and the facts appear to back her up. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 1 in 4 American adults live with at least one disability, making them the nation’s largest marginalized group. Yet they’re often excluded from conversations concerning diversity, equity and inclusion, and they frequently face prejudice, inequality and lack of access despite the 31-year-old federal law.

“The ADA is so young compared to the struggles for equal rights for people of color or the LGBTQ community or women,” Ray points out. “These three movements have been around for a really long time and have progressed a lot further, in my opinion, than disability rights have.”

That said, she’s well aware that until an individual or a friend or family member has a disability, it can be hard for them to recognize the extent of the problems. “It wasn’t until I became disabled that I was like, ‘Oh, my God, there’s this whole community of people that are really being left out, and it’s wrong!’”

The way Ray sees it, a key component of disabled people’s push for equity and inclusion must be building a sense of community and mutual support. To that end, she created DIYabled — a Facebook group aimed at helping disabled folks and their advocates connect and at changing the way the broader population views them. Eventually, she hopes to develop the group into a nonprofit that would educate business owners and other community members about the importance of accessibility, while facilitating a sense of empathy and understanding.

“When you tell someone you’re disabled, they’re immediately like, ‘Oh no, I’m sorry.’ There’s this negative connotation to it,” Ray observes. But thanks to advances in technology, “Today, even more so than ever before, disabled people can be — and need to be — a part of our community.”

Reynolds, who heads up DisAbility Partners’ Asheville office, points out that being disabled can overlap with other marginalized identities. “Not only can you be a wheelchair user, but you could be a Black woman in a wheelchair.” In that case, she notes, “You have three layers of intersectionality.” The nonprofit, which also has an office in Sylva, is a federally recognized Center for Independent Living under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

Disability cuts across every demographic group: People of all genders, races, economic levels, sexualities, ages and more are affected when those rights aren’t protected. At the end of the day, she says, disability rights are civil rights.

In the U.S., continues Reynolds, “People with disabilities have a very powerful and long history of civil rights. Being able to participate in society without having to face barriers, whether they’re physical or other kinds, is a fundamental right.”

It’s great this is one of the more popular MX articles. It will be interesting to learn what all kinds of Asheville and Buncombe citizens think of justice, equity, diversity, inclusion, and wellness (JEDI-W) factors in reality for Persons with Disabilities (PwDs). It’s not looking especially good for PwDs in the big picture.

There are all kinds of ‘Happy Face performance news’ items about PwDs. Meaning mainstream news likes to cover heartwarming stories about non-disabled folks reaching out to brave, smiling PwDs who are overcoming adversity.

Brooke’s story is a first step in covering reality faced by most PwDs.

Here’s a couple of commentaries of mine:

WNC’s missing civic connection to disabled citizens

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/opinion/2018/12/02/wncs-missing-civic-connection-disabled-citizens-opinion/2155612002/

How does North Carolina include Americans with disabilities?

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/opinion/contributors/2016/10/14/guest-columnist-north-carolina-include-americans-disabilities/92046918/

Exactly

And if you speak out to self advocate, you’re marginalized.

What Civil Rights?

Being patronized is all we got.