WEST NC, a new, two-year project to end sex trafficking in five mountain counties, aims to educate the public and service providers as well as empower survivors, says Mamie Adams. She’s been hired by Asheville-based nonprofit Our VOICE to coordinate the project and says its goals center on answering this question: “What does human trafficking really look like, [and] how can we help survivors?”

A $100,000 grant from the Women for Women giving circle is funding WEST NC through Our VOICE, which has long aided victims and survivors of sexual assault in Western North Carolina. The project will cover Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, McDowell and Yancey counties, says Our VOICE executive director Angelica Wind.

The nonprofit also recently received additional support from a state program, NO REST — North Carolina Organizing and Responding to the Exploitation and Sexual Trafficking of Children, says Adams. NO REST aims to “build a better awareness of human trafficking affecting children and youth involved with the child welfare system in [the state], reduce the number of these youth who are trafficked [and] improve outcomes for those who are.”

With support from these two grants, Wind says the big “goal is to end human trafficking in this area.” WEST NC will focus on sex trafficking but no victims of other forms of human trafficking will be turned away, she emphasizes.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines “human trafficking [as] modern-day slavery [that] involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.” The department estimates that human trafficking is “second only to drug trafficking as the most profitable form of transnational crime.”

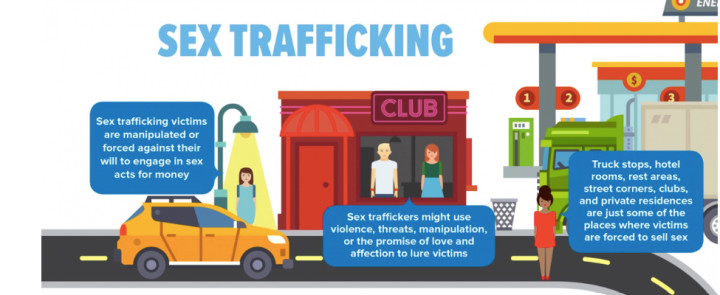

A common perception is that victims are kidnapped from mall bathrooms and forced into prostitution, Adams says. Although that is a possible scenario, more often a runaway teen is lured by a sex trafficker with the promise of love and affection, or young adults are forced by intimate partners to prostitute themselves, she says.

Another common misperception, Adams adds, is that trafficking mostly involves foreigners who are smuggled into the United States and moved from location to location as forced sex, farm or domestic workers. Such cases occur, but the majority of victims in the U.S. are Americans, she says, ranging from runaway teens to LGBT youth who don’t feel welcome or safe at home, as well as women or men already abused and exploited by their intimate partners, she says. “The most vulnerable [to trafficking] are those people who are invisible [or] on the fringes.”

Human trafficking “happens here, in North Carolina and in Western North Carolina,” says Adams.

Exact numbers are elusive, however. North Carolina officials don’t track human trafficking, Adams explains. Even if they did, it’s “not like counting benches in a park,” she says. Victims and survivors “are people who are so underground, so invisible, that it’s hard to fathom the numbers.” And similar to domestic-violence and sexual-assault cases, victims are often reluctant to report human trafficking or testify in court, Adams notes.

Still, Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Polaris Project estimates that there are nearly 21 million victims of human trafficking around the world. Almost 26,000 cases were called into America’s national hotline since 2007, Polaris reports. One hundred and ten of those cases, with 925 potential victims, were in North Carolina last year alone.

In 2009, the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crimes estimated that nearly 80 percent of human trafficking cases involved sexual exploitation, and nearly 20 percent were forced labor.

Nationwide, more than 1,000 human trafficking cases were investigated and 257 federal prosecutions were initiated last year, the Department of Justice reports.

What’s happening in North Carolina? In line with the U.N.’s global estimates, more than two-thirds of N.C.’s 110 hotline cases involved sex trafficking, says Adams.

Fighting human trafficking — particularly sexual exploitation — dovetails with Our VOICE’s mission, says Wind. “But people are really surprised that human trafficking happens in Asheville,” she says. The city is seen as “very progressive [and] socially active. So people ask, ‘If this is happening, why aren’t we talking about it?’”

The reality is that trafficking often occurs in wealthy or relatively wealthy areas where there’s demand, along with access to major highways and an airport, Adams explains. Asheville fits the bill, and it has an active sex industry, she continues. “Where there are sex workers, there’s also human trafficking.”

Wind says she started to wonder, “Why not Asheville?” Nearby major metro areas — Atlanta and Charlotte — have seen significant increases in human trafficking in recent years, according to the Polaris Project.

In Charlotte, community leaders, law enforcement, the legal system and a variety of organizations have stepped up, says Wind. She mentions one example, a survivor-led, entrepreneurship initiative called Market Your Mind that offers such services as transitional housing, GED training, skills development and crisis care. Human-trafficking survivor Antonia “Neets” Childs founded the organization to “encourage, equip and exemplify positive transformations in young women in this highly sexualized society.” On her own journey to financial self-sufficiency, she also founded Neets Sweets, a bakery that helps other survivors become financially independent.

Financial self-sufficiency, say both Wind and Adams, is one of the key goals in comprehensive approaches to helping survivors of human trafficking.

Wind envisions similar, locally led efforts in the Asheville area, sparked by the community education, outreach and conversations that Adams has started leading. But the Our VOICE project “is only part of the solution,” says Wind.

WEST NC will help develop a rapid-response team for Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, McDowell and Yancey counties, Adams says. Team members will help better identify those at risk of human trafficking, those who have been victimized, and those who seek help. And they’ll help survivors get the services they need. Our VOICE and its team partners are “just a conduit to empower [survivors] to take the steps to where they want to be,” says Adams.

Human trafficking survivors need short- and long-term housing, job training, counseling, financial-literacy, medical aid, legal assistance and more, say both women. “I believe the WNC community wants to help survivors in a complete way,” Adams adds. Part of her job will be to identify the people and organizations that can pitch in and work together.

It helps that Our VOICE recently moved its offices into Buncombe County’s new Family Justice Center, a centralized location for agencies, services and resources that assist victims of child abuse, domestic violence and sexual violence. “We need a large network,” says Wind. Relocating trafficking survivors for safety purposes, for example, can be a challenge that requires help from partner organizations, she explains.

That’s where another Asheville-based organization, Helpmate, has already stepped in. The Asheville-based nonprofit “is a supportive partner” in efforts to address human trafficking, including the new Our VOICE project, says director April Burgess-Johnson. “Helpmate’s role is to provide emergency shelter for trafficking victims who are fleeing. We also work to coordinate shelter stays for victims who need to [leave the] area.”

Burgess-Johnson mentions the “unique needs of trafficked victims, including heightened confidentiality and the recognition that [cases] often [involve] multiple abusers. … Being able to have one safe place to access services will increase the ease by which survivors can get all the types of help they may need.”

The Our VOICE project, she adds, will hopefully “improve community awareness of the issue.” Most important, it may “help victims feel safe in accessing the services and support designed to help them escape trafficking.”

Deeper challenges include figuring out why more human trafficking victims don’t come forward or haven’t been helped, says Wind. She cites several keys to the grant project’s success, such as educating law enforcement, health providers and others on the right questions to ask and what to look for in identifying human trafficking victims and at-risk populations.

Adams argues that until we address the root causes of sex trafficking, the problem isn’t going away. “We cannot address sex trafficking without addressing rape and rape culture.” She identifies these as contributing, related problems and asks, “If we look at how we treat rape survivors, how do we think we can possibly help survivors of sex trafficking? How can we be surprised that sex trafficking is common when rape is so common and prosecution is so lenient?”

Adams adds that human trafficking is “hidden more than ever before because transactions [happen via] the internet and mobile phones.” Victims can be moved before anyone’s aware something is going on. “You’re more likely to be in contact with an at-risk person than someone who’s already been trafficked. Once they’re trafficked, they’re invisible,” she says.

A big part of the project’s education efforts will include outreach to local hotels, airport workers, truckers, law enforcement and others who might be most likely to see the signs of trafficking, says Adams.

“People need to be talking about this,” says Wind. “No community is immune.”

Want to help?

Our VOICE needs donations and care packages for human trafficking victims. To help, call 255-0562.

For more information or to request a community-education event on human trafficking, contact Mamie Adams at 255-0562.

Need help?

To report human trafficking, call the national hotline at 1-888-373-7888.

To seek local help, call Our VOICE’s crisis hotline: 255-7576.

Want to learn more?

See “Insidious and Elusive,” a June 6 article by Lea Hart with the Asheville-based news nonprofit Carolina Public Press. CPP will host a Friday, Aug. 12, “newsmaker” forum focused on human trafficking from 8:30-10:30 a.m. at Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Center for Graduate Studies of Asheville. For more information, call 774-5290 or email tgeorge@carolinapublicpress.org.

wow, to learn more about the history of the democrat party of slavery and it’s untaught formation (untaught in government screwls),

you should not miss the blockbuster documentary ‘Hillary’s America’ by Dnesh Dsouza in which he explores the answers to the question: Why is democrat party history never taught in government screwls ? Did you ever wonder that too ? Have you ever heard anyone ask that question ? He includes lots of democrat history in this Hillary documentary for optimum understanding!

this is what human trafficking is defined as: The U.S. Department of Homeland Security defines “human trafficking [as] modern-day slavery [that] involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.”

and this is what media & ‘socalled rescue (i.e. $$$ seekers) tell everyone it is: “human trafficking [as] commercial sex .”

No, ‘most’ teens aren’t lured in with romance and flowers. Most teens who are runaways need shelter & food, and if this socalled trafficking group needs two years to figure out that the best way to ‘combat’ teen sex work is to make sure they have that, then i weep for your backwards country now and forever. .

There’s an easy solution here. Legalize prostitution and this goes away. But of course you have 2 groups ironically on the opposite spectrum who oppose this. Feminist and women because they know that they lose the power and religious fools who call it immoral.

Yea, for a city that screams in fright when a female breast is bared in public, legalized prostitution is going to go over really well here.

Also, how dare those weaker sex type female feminists advocate for not being abused by the sex trade industry by most likely your GOP type preacher, boss, accountant or neighbor. Why can’t we live in the world of that show Mad Men when it was socially acceptable to pat a woman on the ass as she walks away?

I miss those days.