Every election Corinne Duncan has worked since joining Buncombe County Election Services in 2015, she says, has felt more intense than the one before. Ever more people are voting, requesting information from the office she now directs and scrutinizing the electoral process.

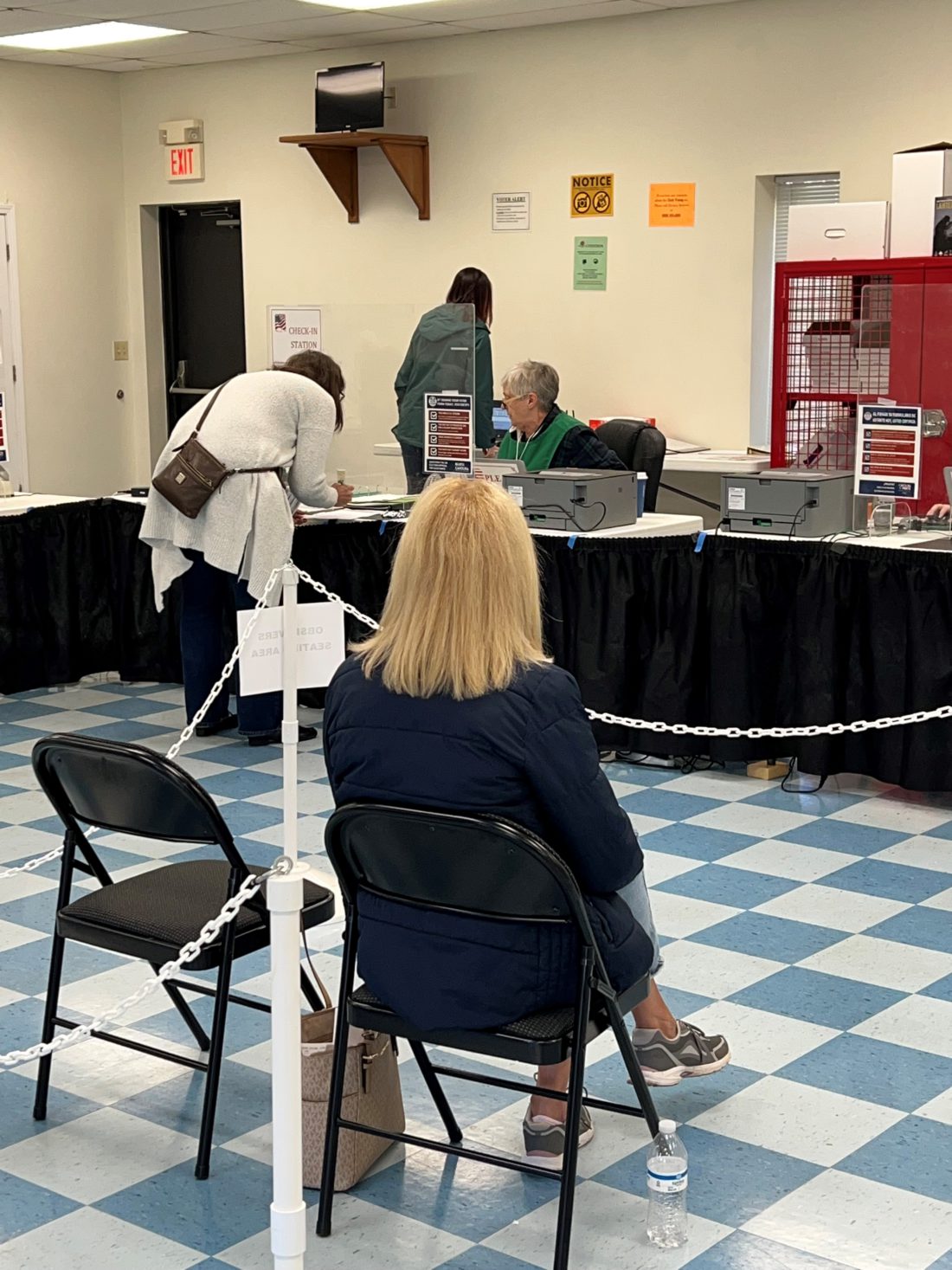

And an increasing number of citizens, Duncan continues, want to take an active part in that process by serving as poll observers. As their name implies, poll observers work inside polling locations and are responsible for watching voters and election workers as citizens cast their ballots. They take notes of any irregularities, such as a location running out of ballots or a voting machine malfunctioning; they may also ask procedural questions of election officials and report concerns to the chief judge.

The role has traditionally been a low-key check on election officials to make sure voting runs smoothly. But as allegations of voter fraud in the 2020 election — the vast majority of which have been disproven — continue to reverberate among some voters, several conservative activist groups are recruiting and training poll observers in the name of “election integrity,”

Local election officials are taking notice. Amid those recruitment efforts, reports of aggressive observers elsewhere in the state and rising interest among first-time workers, Duncan’s office held its first information session to lay out the rules and regulations regarding poll observing. The hourlong Oct. 13 event drew roughly a dozen online and in-person participants.

“We thought, ‘How are these people getting trained? Where are they getting their information from?’” Duncan explains. “And so that signaled to us that it was time to do an information session.”

By the book

Political party chairs are responsible for appointing observers, who must be registered voters in the county they wish to serve. In Buncombe County, those people include Democratic Party Chair Jeff Rose and Republican Party Chair Glenda Weinert. (Green and Libertarian party leaders may also appoint observers, but Duncan says they have not done so in recent elections.)

Names of appointed observers must be turned in to Buncombe County Election Services five days before an individual’s service, making Thursday, Nov. 3, the last day to qualify during the 2022 fall election. The county requires that each worker participate in a four-hour training session and assigns each observer to a specific polling location.

Duncan explains that poll observers must follow a strict set of rules, including not speaking to voters or other election workers except for the chief judge, who is responsible for overseeing each precinct if issues arise. Observers work four-hour shifts and are supposed to be located where they can see and hear interactions between poll workers and voters. However, they aren’t allowed to enter a voting booth, look at ballots or take pictures. No more than three observers from a single political party can work at one polling place at the same time.

While Duncan says Buncombe County Election Services doesn’t have complete data regarding poll observers over the years, she says interest has grown. The most recent numbers show that 274 people served as poll observers on Election Day in Buncombe County during the 2020 election and 93 observers served on Election Day during this May’s primary.

Call to action

Training and recruitment of poll observers have usually fallen to local party chairs and election boards. But following the 2020 election, a number of state and national organizations emerged with a focus on poll observers.

One state group active in Buncombe County is the North Carolina Election Integrity Team, headed by Jim Womack. Womack, a former Lee County commissioner, chairs the Lee County Republican Party and is a member of the state GOP executive committee. According to NCEIT’s website, the group aims to “create and maintain an active, ongoing, trained citizen election integrity task force in key counties in 2022” and make the electoral process “easy to vote, but very hard to cheat.”

The Asheville Tea Party, a conservative local nonprofit, held several poll observer training sessions together with the NCEIT in October. Reporters were not welcome to attend the sessions, with one online newsletter stating, “‘the media’ have relentlessly ridiculed the Election Integrity Network and our work to build an election integrity infrastructure throughout the nation, comprised of patriotic Americans who want to save our elections.”

Representatives from the Asheville Tea Party did not respond to several requests for comment. Womack responded to an interview request by directing Xpress to the NCEIT website.

NCEIT is in turn overseen by the national Election Integrity Network, a multistate coalition of conservative organizers led by Cleta Mitchell, a lawyer who helped represent former President Donald Trump as he tried to overturn the 2020 election. Mark Meadows, Trump’s former chief of staff and former U.S. House District 11 representative, is also a senior EIN partner.

EIN representatives did not respond to multiple requests for comment. However, in her introduction to a training document for the organization, Mitchell writes, “The powers-that-be in America don’t want citizens to discuss the 2020 election or to question the process that millions of Americans believe was less than fair. … Ideological advocacy groups and Democratic party operatives and lawyers descended upon courthouses across the nation demanding — and getting — changes in the duly enacted state election laws.”

Rose, with Buncombe’s Democratic Party, calls the recruitment groups “a concern,” noting that he was not aware of any liberal-aligned organizations leading similar efforts. He suggests that some citizens may be misled by the way these groups cast the role of poll observers. That could lead some observers to become confrontational or disrupt elections, he argues.

“You’re not an auditor of the election; you’re not there to correct anybody. I think the term ‘observation’ is very literal, in the sense that you are there to look at what is going on. So, I think there’s some misconception when I see groups advertise about what an election observer is,” he says.

But Duncan says that so far, she is not concerned about outside groups like NCEIT. She says all observers must follow rules laid out by the N.C. State Board of Elections, regardless of any outside training they receive.

“We heard this same [concern] in the primary, and we really didn’t see any problems in the primary,” Duncan says. “And at the end of the day, everybody has to have to follow the same rules, and our poll workers have been informed of that.”

“I think people just want to feel like they’re contributing,” adds Republican Chair Weinert. “There’s been a real concerted effort to make sure that, regardless of what side of the political extreme they’re on, that they’re still required to learn how to be an observer and to do it correctly.”

Watching the watchers

Despite thorough training from local elections services, however, some issues regarding poll observers have popped up across the state. Results from a survey of county elections directors by the N.C. State Board of Elections revealed dozens of instances of observers becoming confrontational with voters and election workers and disrupting the electoral process during the May primaries, including reports from Haywood and Henderson counties.

No such problems have yet occurred in Buncombe County, says Duncan. “We’ve had a few issues but not malicious issues. The one that sticks out, in my mind, was an observer who misinterpreted her role. It was just question after question after question after question of the chief judge, which was interrupting their purpose,” she says.

In August, the NCBOE attempted to rein in poll observer behavior when it unanimously approved new temporary regulations. Among other changes, the new rules would have prevented observers from standing too close to voting machines — where they could potentially view marked ballots or confidential voter information — and give elections officials authority to remove observers who tried to enter restricted areas, interact with voters or disrupt election proceedings.

Those rules were rejected by North Carolina’s Rules Review Commission, a state executive agency that reviews and approves rules state agencies have adopted, less than two weeks after their introduction. The RRC is chosen by the Republican-controlled General Assembly and consists primarily of Republican appointees.

Rose sees the veto of the rules as potentially enabling poor conduct among poll observers. “Ambiguity can be really helpful if you’re looking to cause trouble, because there’s nothing that legally says that you cannot do X, Y and Z,” he says. “I do think there was kind of a wink and a nod to some of those more fringe groups that are doing their recruiting programs.”

Despite the potential problems, Rose believes that the hands-on experience poll observers get might also quell some of their concerns about how elections are run.

“The level of work that goes into making sure that elections are fair in North Carolina, at least the tabulation of the votes, as far as I’m concerned, is extraordinary,” Rose says. “Once you understand what the team does and what policies are in place, it’s harder to believe the story that you see on TV about somebody grabbing a thumb drive from a trash can and just uploading results or something like that.”

Weinert agrees. “People are just looking for assurance. And regardless of what your opinion is or your perspective, I think we all want the same thing, and that’s to have a fair and honest election,” she says. “Whatever motivation brings people to the table or gets them out, I want people to not just sit on the sidelines.”

Naive expectations that proud boy poll observers might only mean well and share the American way to safely count every legitimate vote is contradicted by the transparent tRUmp putin Bannon rules that “heads they win, tails we lose.” Disruption, chaos, and claiming victory, and fraud is the only way you can lose you lose may be the way toddlers play games but it’s deadly for democracy.