In 2021, Joe Minicozzi, principal and founder of local urban planning firm Urban3, noticed a disturbing trend. As he and his peers analyzed Buncombe County’s latest round of property revaluations, they discovered that homes in historically poorer neighborhoods had disproportionate increases in property values compared with properties in richer parts of the city.

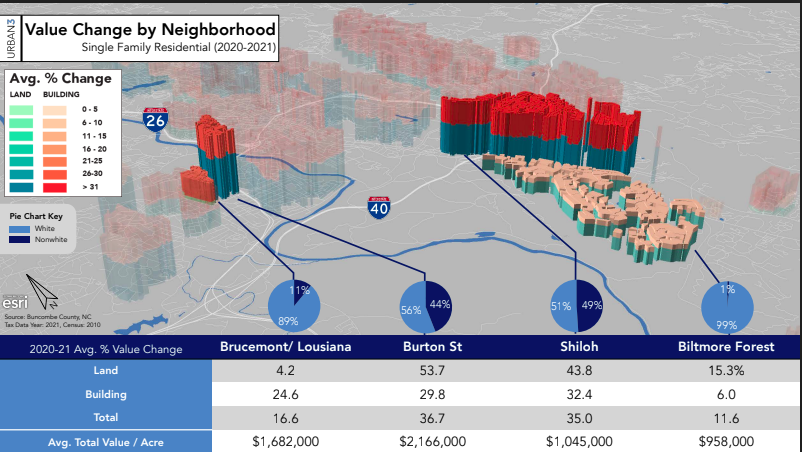

Areas such as Burton Street and Shiloh, both of which are well over 40% nonwhite, saw single-family properties valued at significantly higher prices in 2021 than in the prior year — 36.7% and 35% higher, respectively — significantly raising tax burdens on many of Asheville’s poorest homeowners. Many wealthier, whiter neighborhoods, however, saw much less of an increase. Single-family property values in Brucemont, which is adjacent to Burton Street and 89% white, increased by just 16.6%; values in Biltmore Forest, which has a 99% white population and is across Hendersonville Road from Shiloh, increased by only 11.6%.

Many high-priced homes, Minicozzi found, have seen their assessed values fall substantially short of their sale prices. The home of the late Biltmore Farms head, George Cecil, in Biltmore Forest, for example, sold in September 2021 for $9.5 million — a Western North Carolina residential record — but had been assessed at only $4.9 million.

“How could the assessor be 50% off?” Minicozzi asks. “If you scored a 50% on a test, would you be considered succeeding in that class? Of course not. That’s an absolute failure in estimating value.”

Urban3 prepared an extensive report analyzing the trend, evident in many other U.S. cities, and shared its findings with Buncombe Board of Commissioners Chair Brownie Newman. In response, Newman tasked county Tax Assessor Keith Miller with forming an ad hoc committee to provide guidance for future assessments and identify potential equity concerns.

The resulting committee consisted of three real estate professionals (two from one firm, Christie’s Real Estate), city of Asheville Director of Equity and Inclusion Brenda Mills, three at-large community members and Ori Baber, an Urban3 analyst. The group recently concluded its work, having met 14 times since November 2021, and as of press time was scheduled to present its recommendations to the Board of Commissioners Tuesday, July 19.

Moving numbers

According to Miller, the county’s assessment numbers for each property are generated via a formula that considers each structure’s type, market data and sales figures. The resulting values, he asserts, are simply reflections of market forces that exist outside of the control of the assessor’s office. He denies any suggestion that his office engages in any intentional over- or under-assessing of properties.

“Our appraisers have no idea who lives in these houses. We don’t know their skin color, their ethics; we know nothing. We know the property characteristics and what the sales numbers are,” he says.

Time is also a factor. Miller says that the county’s property assessments are really only accurate on the day they are generated. As time passes and property values increase or decrease, they can drift away from the number generated when the assessment was made.

“We just interpret what the buyers and sellers are doing,” Miller says. “In the areas that show larger growth, the numbers show what people are paying for properties. That’s just what the market is.”

“There is no proof of inequities,” Miller continues, when asked about what looks to be trends specific to certain areas of the city. “No one, Urban3 or [county consultant] Syneva, has said there is clear evidence of bias toward different types of neighborhoods. These properties that were overvalued and under-assessed, if you look at the map, they are scattered all over the county.”

But Baber claims Urban3 would have presented evidence of neighborhood-level inequities if given the opportunity. He says County Manager Avril Pinder constrained the length and content of the material Minicozzi was allowed to present to the committee.

“If you are white, you are eight times more likely to get an assessment discount of value than if you are Black — period,” adds Minicozzi, referring to tax values that fall underneath sale prices. “That is a textbook definition of bias.”

Conflicting perspectives

In keeping with Miller’s view, the ad hoc committee’s recommendations do not include any changes specifically addressing racial or economic inequities. Instead, suggestions include expanding access to the valuation appeals process, changing assessments for properties used as short-term rentals, boosting staff levels in Miller’s office and increasing levels of compliance around reporting property improvements.

Discussions during the final meetings of the committee, however, suggest disagreements around equity issues. Members considered two “ratio studies,” reports that evaluated discrepancies between a property’s assessed value and its eventual sale price.

The first, conducted by Urban3, found that the county’s most expensive homes had been assessed at about 78.3% of their sale price on average, while the least expensive homes were assessed at about 84.5% of their price — a difference of more than 6 percentage points. The second, commissioned by the county from consulting firm Syneva Economics, found virtually no difference in assessment between homes of different prices.

Baber of Urban3 argues that the Syneva study is off-target. He says that report used data that had been adjusted through “sales chasing,” in which assessments for houses that have recently sold are revised using data from those sales. Those sales only covered 2% of all Buncombe properties, he continued, meaning Syneva’s model wouldn’t be accurate for the remaining 98% of homes.

Conversely, it’s the Urban3 model that Miller feels is misleading. “It uses old sales data and old assessment data, which you cannot do,” he says. “If you compared a sale today back to when it was assessed, it’s going to look like the property was under-assessed. The values will sometimes look like inequities are there when they may not be. The market may just be responding differently to different areas of the county.”

Many Asheville homeowners of color are feeling the brunt of the property tax increases and are struggling to process these opposing views. Kristyn Harris is the fundraising coordinator for the Racial Justice Coalition, which she says has been following the ad hoc committee’s work.

“It was clear last year that Black homeowners were going to pay way more than their fair share and that this was going to make Buncombe County even less affordable for our dwindling Black population. We thought the property tax appraisal should have been scrapped and done again, this time with a racial equity lens,” Harris says.

“Buncombe County staff completely ignored the data that Urban3 had discovered and instead presented another analysis, one that was not conducted according to industry standards, which effectively whitewashed the property tax inequity problem and declared, in essence, that there was no problem,” she continues.

Eric Cregger, county tax systems analyst, wrote in a communication to the committee prior to their June 1 meeting that the assessor’s office’s procedures had been reviewed by state officials and industry professionals and were determined to be sound.

According to Newman, multiple perspectives may be considered when Commissioners get their turn to weigh in. “I’m aware that Syneva Group and Urban3 did not reach identical conclusions in their analysis,” Newman said. “I expect the board will want to hear about the different analytical approaches taken by the different groups to understand what can be learned from each of the different analysis that has been undertaken.”

Closer to equity?

For Harris, the committee’s recommendations are a step in the right direction, but much work remains to be done.

“The biggest concern that we have is that they don’t fully address the root cause and harm done to the Black community,” says Harris. “Because of the information provided to the committee, and the information withheld, it’s no surprise that their proposed solutions won’t really address the core issues. Moving forward, we wonder how the county can be intentional about providing real solutions to a problem they don’t fully understand.”

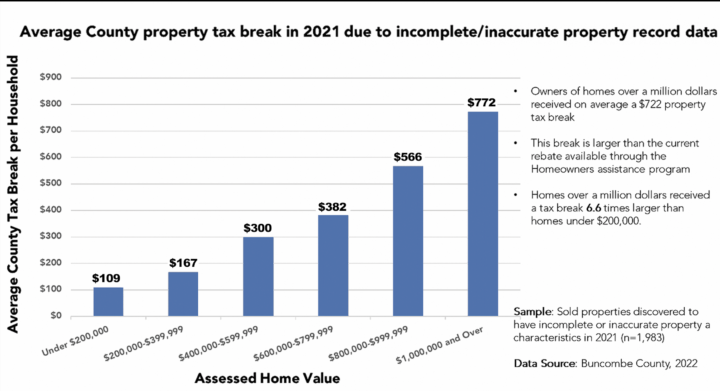

Miller acknowledges that Buncombe has failed to capture the full value of property in the county. In a sample of about 2,000 home sales from 2021, for example, assessed values fell roughly $96 million short of actual sale value. Asked why this was the case, he points to unreported improvements that had increased their value; he says the county’s valuation formula is sound and that the responsibility to record improvements falls on homeowners, not the assessor’s office.

But to Baber, that difference in value points to a need for bigger changes in the county’s approach. “This means that in 2020, and perhaps many years prior, these homeowners have been receiving a significant tax break,” he says. “If this trend holds up across the entire housing stock, there could be billions of untaxed value in the county. This untaxed value mostly exists in more expensive homes, so rich homeowners are benefitting from this flaw in the assessment system.”

Next, county commissioners will hear the report and have the opportunity to ask Miller about the ad hoc committee’s recommendations. While differences of opinion persist among Miller, Urban3 and others about how to best interpret the data and move forward, Miller suggests solutions to improving the process may best come from outside of his office.

“I understand the concern from property owners,” Miller said. “I don’t offer a solution. Every county in North Carolina lives by the same statutes. There hasn’t been a solution created for it yet. Will there be? I don’t know.”

Edited at 1:09 p.m. Aug. 2 to correct quote attribution for Kristyn Harris of the Racial Justice Coalition

This is not a race issue. This is an arithmetic issue by somebody who does not understand the concept of percentage increases . The simplest way to explain this is with an example. The average tax rate in Buncombe Count is 0.67%. If I take a property in a poor neighborhood that was valued at $150,000 the property taxes are $1,005. If the property value increases by 50% to $225,000, the property taxes increase to $1,507.50 . This is a net increase of $502.50. Now let’s take a house valued at $1 million. The property taxes are $6700. If the property value increases by only 25% to $1,250,000, the property tax increases to $8,375. This is a net increase of $1,675 or $1,172.50 more than the 50% value increase of of the lesser expensive property. Stated another way, the rich person owning the $1 million house that increased only 25% in value paid much more in taxes on that increase than the person with the $150,000 house whose value increased by 50%. In fact, the rich person paid 2.33 times more on the 25% increase in value than the person owning the house originally valued at $150,000 paid on their 50% increase in value. It is also important to note that percentage increases are always larger with smaller numbers. For example, an increase of $10 to $20 is a 100% increase. But another $10 increase from $20 to $30 is only a 33% increase and so on. It simply is natural in a rising market for the percentage increases in lower valued properties to be larger than more expensive properties while the nominal dollar increases in the value of more expensive properties will be much greater. In the example above, the $150,000 propery only increased $75,000 with a 50% increase, but the $1 million property increased $250,000 with only a 25% increase. I think the real issue of the people complaining about this is that we don’t have graduated property tax rates similar to graduated income tax rates where people who make more money pay a higher percentage of their income. If we had graduated property tax rates then people with higher property tax values would pay a higher (i.e. more than .067%) property tax rates. But this is an issue for the politicians. It is not a problem with the appraisal system.

Percentage increases can be incredibly misleading when used in comparisons.

FOR EXAMPLE:

House in Shiloh goes from 200 to 300K; a 100K increase. Why? Because lower priced houses wherever they may be are being bid up considerably. Percentage increase? 50%.

House in Biltmore Forest increases from 2M to 2.5M; a 500K increase. Percentage increase? 25%.

It really is that simple. Lower priced home increased on a % basis more than higher priced homes, hence a larger tax increase %. Homes go up in value so you pay more. That’s how property taxes work.

Look at the discounts in this video. They aren’t consistent. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqbPjM3AMeo&t=4s

It’s not that simple. Open up the County’s GIS and poke around Biltmore Forest over by the Parkway. You will find houses LOSING VALUE over the last 10 years. That’s right. Losing value. You don’t find that in Shiloh. Additionally, there is a bias in the methodology in the computer software, but also in how the standards are practiced. Take a look at this 3 minute video and look at the numbers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqbPjM3AMeo&t=4s

You should lead by example. Since your home was assessed for $433,500, but your Zestimate is $818,600, I hope you are paying the County and City double your tax bill.

Your work isn’t wrong… assessed values are MUCH lower than current market rates, as your home indicates. But much of your alleged causation is suspect.

zestimate isn’t the most credible source. Have you read about how they got their hand slapped for price inflating and speculating? Plus, Zillow thinks I live in a single house, not a duplex. It’s a different comp.

Click on the link above. Do the same thing. And since you found my house, compare me against houses on Kimberly or by the country club.

It’s not consistent, and that’s the problem. We should all get the same benefit or discount.

And yes. I’d gladly accept paying by 100% valuation. Everyone should. It’s the law. And if the software is undervaluing me, then change (or correct) the software.

What the video link shows in my comment is that the software isn’t consistent. My value I may be valued below market, but I am not losing value like those that I show in the video.

Realtor.com: $724k

Redfin: $731k

I’m sure your CAMA model says something close.

I encourage you to publish a tool that allows people to quickly calculate their “correct” tax bill based on your analysis. Those folks, including yourself, are welcome to make a cash donation to the government. Great opportunity for you to lead by example.

“…the responsibility to record improvements falls on homeowners, not the assessor’s office.” Which always happens, because people love paying more taxes. Ahem. Miller is right – it’s a flawed system, period. Sounds like NC statutes need changed requiring more in-person appraisals vs. just munging the data with new variables.

I believe we’re having the wrong conversation. There’s so much money flowing through our area from tourism, which is then wasted on the bizarre unnecessary 75% advertising rate for more tourism. All property owners should be receiving massive rebates on property taxes, financed by surplus BCTDA funds (to which all resident property owners contribute directly and/or indirectly by our very existence here as citizens in this place we call Home).

And properties being used as Airbnbs should be taxed at a higher rate than homes used as primary residences or long-term rentals.

Here is another inconvienience….get the assesors to actually SEE the property, at least once every appraisal cycle !! There is a location on SFB that is appraised at 242K, the building value is 155K , and the land value is 87K. It all seems straight forward and the math checks out…the BIG however is the house has been condemned !! The roof is failing and has visible plant growth through it, there have been several vagrants that utilize the lower area for shelter, broken windows. SO HOW CAN THE BUILDING VALUE BE 155K ? ?