Each place deals with its dead differently. Historically, big cities often gathered their deceased into large cemeteries, which in the 21st century offer digital maps and databases where grave-seekers can find eternal resting places in seconds. Such technological amenities are impractical in places like the Great Smoky Mountains, however, where gravesites proliferated in nooks and crannies across a large area.

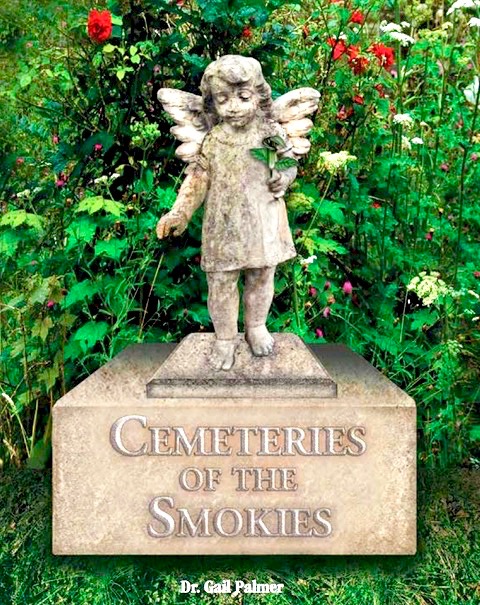

A new 700-page book, Cemeteries of the Smokies, published by the Great Smoky Mountains Association, serves as an exhaustive guide to graves in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Through photographs, oral histories and scholarship, the tome also sheds light on the unique world of Appalachian burial lore and traditions.

Author Gail Palmer meticulously documents gravesites, offering road and trail maps to 4,737 graves. She collects the histories of the cemeteries, the communities they served and the colorful individuals who were laid to rest. In doing so, she brings to life a culture whose physical markers are fading with time but whose stories resonate throughout the hills and hollers to this day.

Devil in the details

Definitive records of permanent European settlers in the region that’s now Great Smoky Mountains National Park date back to the late 1700s. Most settlements remained small, with subsistence farming as a primary mode of survival, until the logging industry came to the area in the decades after the Civil War. Using their tombstones, Palmer’s book strives to provide an accounting of the lives of these settlers, including dates of birth and death, epitaphs and familial ties for every grave listed, when available.

The book also tells of the unique burial customs of the region. It was common to scrape the ground in cemeteries completely bare, so they resembled a swept dirt floor. Many burial grounds had no vegetation, just rows of mounded graves. The graves usually faced the rising sun in the east, reflecting the belief that resurrected souls will be looking in the right direction when Jesus returns.

Grave markers were often simple field stones, with a larger one at the head and a smaller one at the foot of the burial plot. It wasn’t until later in the region’s history, during the 19th century, that engraved markers became commonplace.

The 152 known cemeteries within the park boundaries are subdivided by region in 17 “stories” that structure the book. Each story is named for a place, such as Cataloochee or Greenbrier Cove, and tells the history of that place.

Some stories of graveyards explain who donated the land and how the deeds were passed from family to family. Most established cemeteries came into existence in this way, with individuals giving an acre or two for the use until official town facilities were established for the community.

Living before dying

Cemeteries of the Smokies continues the Appalachian tradition of telling tales of larger-than-life characters, highlighting vibrant community members. There’s Granny Pop, who spotted a panther in a tree on her way home from “visitin’ on Little Catalooch” one evening. To stave it off, she followed conventional wisdom and dropped her clothes on the trail, piece by piece, so the cougar would attack the articles of clothing rather than follow her. The teller of this story, Steve Woody, claimed that Granny Pop “came in like Lady Godiva, without a stitch.”

Or there’s Edd Connor of Oconaluftee, who, after a stroke in 1919, made a coffin of his own design from a tree he planted decades earlier as a young man. This in itself was not unusual; Palmer writes, “It was common at that time to make arrangements in advance for your funeral.” Connor took things a bit further, though, designing a white linen burial suit for himself. He recovered from the stroke but had become so fascinated by the idea of his own funeral that he held the event anyway, “so he could enjoy it and could see who would come and what they’d say.” Connor didn’t actually die until 1937.

Not all the stories are full of humor and whimsy, however. Many tell of the unrelenting danger that stalked the settlers: dramatically high rates of infant mortality, logging accidents, typhoid epidemics and the Civil War.

Some recount a different kind of tragedy, such as the story of the Hazel Creek community and its cemeteries. Burial records show that prior to 1860, there were only four family names in the whole area — not unusual for a place as sparsely populated as the Smokies. Things changed by the end of the century, as the logging and mining industries exploded across the Southern Appalachians. Workers flooded the area, bringing families and contributing to population growth.

Then the Tennessee Valley Authority announced plans for the Fontana Dam. The dam would create a new lake, which would fill an area of more than 10,000 acres. Families were forced to move, whole gravesites were disinterred and resentment sprang up toward authorities, which lingers to this day. (For more about the Hazel Creek community and the legacy of the Fontana Dam, see “Washed Up: Hazel Creek Author Daniel Pierce Details Community’s Convoluted Past,” June 14, Xpress.)

Despite the lingering sadness of some of these histories, Cemeteries of the Smokies elicits the good humor ingrained in Appalachian culture and spins an entertaining yarn about dying (and living) on the frontier of the Great Smoky Mountains.

“As all things eternal and primordial reappear, so all things mortal return to earth. Honor, old age, probity, constance, virtue, and gentleness are all gathered into the cold tomb.”

(Francis Quarles, 1638)