From tense school board meetings and teacher protests to uninvited state mandates, public school leaders had their hands full in 2023.

As the calendar turns to 2024, a decades-old debate about district consolidation has reemerged, and both school boards are scrambling to implement new policies to comply with a controversial state law regarding parental rights.

All this transpired as Buncombe’s two superintendents settle into their relatively new roles. In late 2022, Buncombe County Schools Superintendent Rob Jackson replaced the retiring Tony Baldwin, who had served since 2009. In June, Maggie Fehrman became Asheville City Schools’ fifth leader since 2010, not including four interim superintendents.

A top issue for both districts is a persistent opportunity gap between white and Black students. In reading alone, 87% of Black students in ACS and 79% of Black students in BCS scored below grade level in proficiency compared with 25% and 39% of their white peers respectively, during the 2021-22 school year, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

While both superintendents struggle to solve that problem, state laws entice parents to choose private schools over their public counterparts, draining public schools of students and funding.

Atop all that, state legislators passed a law in October that orders a feasibility study of merging the county’s two school districts

Xpress sat down with both district leaders in December to break down 2023’s challenges and their visions for the year ahead for local public schools.

Fehrman battles opportunity gap, declining enrollment at ACS

Fehrman spent much of her first semester leading Asheville’s urban school district doing what many superintendents say they do when starting in a new place — listening and learning.

Fehrman met with principals and central office administrators over the summer and regularly toured schools to experience “a day in the life” of teachers and students at the district’s nine schools.

Those listening sessions led Fehrman to establish three priorities for the district: creating a sense of belonging for all students; ensuring the curriculum is challenging and relevant; and helping teachers and staff make every second count toward student success.

After repeating those goals at various meetings, Fehrman says she’s starting to hear conversations framed in those terms at the school level, starting with establishing a sense of belonging for every student.

Not everyone feels as if they belong, it turns out.

“After listening to the staff, students [and] community members, there isn’t an equal sense of belonging for every stakeholder. Our community members and students and staff of color felt like they hadn’t been included as much or didn’t feel as much of a sense of belonging in our school system. Staff felt that they hadn’t been as involved in decision-making as much. So I really wanted to start this whole idea of creating a sense of belonging for every stakeholder,” Fehrman says.

If they don’t feel that they belong, there’s no chance of achieving success, she adds.

Opportunity gap

But solving the issue that has haunted many superintendents before her remains a work in progress.

Fehrman says despite partnerships with many after-school organizations, small class sizes and other efforts, the district still struggles with achievement for Black students.

“I’m not saying that our teachers are not experts, but they’re being asked to do so much that they’re not able to, I think, really focus on their expertise and their professionalism as teachers,” Fehrman says. “Something’s happening. … Have we not given them enough instructional time? Are they being asked to do all these other duties that aren’t allowing them to really focus on what they’re there for, which is the core teaching for our students?”

Mental health issues also have been a greater challenge for students than in the past, based on Fehrman’s observations, and she says managing that could be eating into teachers’ instructional time.

Regardless of the multitude of challenges, there are examples of schools getting it right, Fehrman acknowledges. On a tour of PEAK Academy, a Black-majority elementary level public charter school established to combat the city’s racial opportunity gap, Fehrman says she saw teachers teaching and students engaged.

“You saw a sense of belonging, you saw every student feel like they are a part of a classroom and a valued part of the school, you saw the teachers not giving up one second in their classrooms [that wasn’t focused] on instruction,” she explains.

Fehrman also was impressed with how PEAK staff handles discipline. She says there is both accountability and forgiveness with a minimum amount of lost instructional time for students.

“I think one of the key things we have to do is respond to students that are in challenging situations with empathy, not sympathy. And that means we empathize with someone, we recognize the challenge that they have, but we still are holding them to high expectations, and giving them the resources and strategies to overcome that,” she says.

Conversely, a sympathetic approach would be allowing a student to sleep on his desk because he didn’t get enough sleep at home, she explains. An empathetic approach acknowledges students’ struggles but insists they still strive to learn.

It all comes back to fostering a feeling of belonging in all students, and one way to do that is by recruiting Black teachers, she says.

Fehrman hopes to address that by promoting administrators of color from within, showing potential hires that ACS is a place where advancement is possible.

“I think diverse teachers are so important for our students,” she says. “[I want] every single student to see staff of color in a leadership role, and particularly teacher leaders.”

Teacher burnout

And it isn’t just teachers of color who need encouragement.

As Fehrman has heard repeatedly over the last seven months, a top complaint is that teachers’ pay has not kept up with Asheville’s high cost of living. The state sets teachers’ base rate of pay, and the county adds supplemental pay, giving district leadership no say in the matter. Instead, Fehrman focuses on workload.

“They’re exhausted. There’s a lot coming at teachers, a lot of expectations. … What do we do as a central office to take things off of our teachers’ plates? Because they’ve been piled on, piled on, piled on without this conscious effort and reflection to say, what’s working, what’s not working? If it’s not working, let’s stop doing it. Why are we wasting time and energy?” Fehrman says.

Fehrman believes she can reduce inefficiencies with a recently announced reorganization of the district’s central office, which exists solely to support schools and principals, she says.

“Our goal should be: What can we take off of our schools’ plates? How do we make sure they get the resources they need in a timely manner? How do we break down barriers so that they don’t have to work on those barriers themselves?”

Over time, she says, the central office has lost cohesiveness, leaving schools guessing which department can help address a specific problem.

“That’s confusing for the school,” she explains. “They will call four people. We’ve got to stop that.”

Once a logical framework is created, Fehrman envisions moving most district staff back to the school level.

“We’re a small enough district where we shouldn’t have much centralized [staff],” she notes.

The year ahead

With declining enrollment for the last seven years, ACS is serving its fewest number of students since at least 2011-12, according to district data. That means less money from the state, and more empty space in schools.

Fehrman had these trends top of mind when she asked the Asheville City Board of Education to approve an internal capacity and enrollment projection study in November.

Most of the district’s schools are well under capacity. Fehrman launched a study of its two middle schools — Asheville Middle and Montford North Star Academy — to consider consolidating them into one building. She hopes the enrollment projection study will help inform the district on why it’s losing students faster than neighboring BCS and where they’re going.

She sees these studies, as well as fostering a greater sense of belonging in students, teachers and other stakeholders as her biggest challenge in the year ahead. But she has grander dreams, as well.

Once a foundation is set and strong, Fehrman wants to go beyond the public education model to add more hands-on learning opportunities.

“Is there an opportunity within our current structure to think differently about education? Instead of let’s learn about this, you know, through notes or through a lecture, I really want to see an opportunity for our students to learn through experiences,” she says, like a bike and coffee shop where kids can learn about the physics of repairing bikes and the business of running a shop.

Schools could be open later, so students can spend the day at an apprenticeship. Schools should look more like community centers, she suggests.

But before any of those dreams can be realized, Fehrman knows there are pressing issues at hand for the shrinking district.

“We live in a city that has a lot of big-city issues for a small town. And that’s been surprising to me coming from Atlanta. Atlanta’s got lots of problems, [but] it stays out of the schools more than it does here. I think there’s an opportunity to partner more with the city and the county government on how we create schools as that place of refuge for our students,” she says.

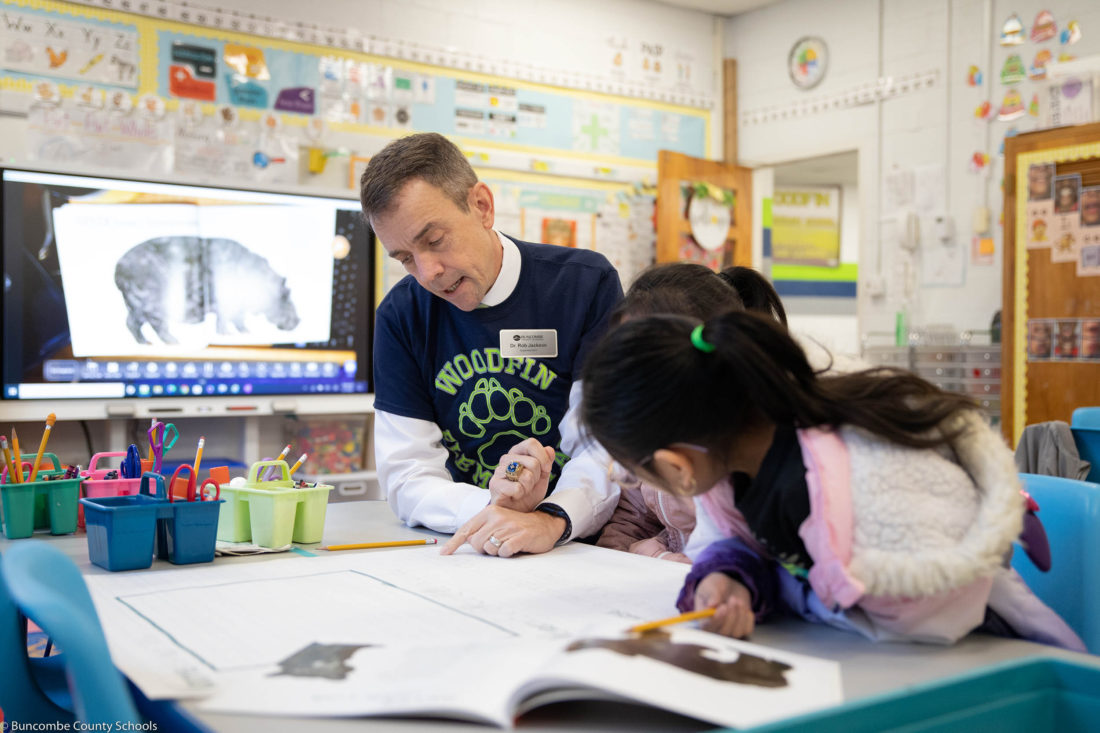

Jackson sets sights on increased growth at BCS

At the conclusion of his first year at the helm of BCS in November, Jackson was ready to celebrate some early signs that the district was headed in the right direction.

Of the district’s 45 schools, 20 exceeded learning expectations in the 2022-23 school year, eight more than last year. The graduation rate is the highest in the district’s history, according to Jackson, and tracks 5 percentage points higher than the state average. ACT scores are also at their highest in seven years across the district, according to district data.

Even overall enrollment was up slightly last semester for the district after several down years surrounding the pandemic, Jackson says.

“That’s not the case in many public school systems. And so we’re really excited that we’re growing as a school system, particularly in an area where parents have many choices [such as] charter schools, private schools, home schools, etc. [It’s] a huge compliment that they’re entrusting us with that which is most precious to them.”

One of Jackson’s main goals for 2024 is to make sure that trend continues even while a state opportunity scholarship program incentivizes parents to consider nonpublic options for their children. Jackson says he is not bothered by the growing opportunities in charter and private schools.

“Competition certainly makes us all better. And so if we become better at serving our students and families and communities because we recognize that other opportunities exist, well, that’s better for students anyway, and so I’m fine with that. But I do believe that our public schools are the best choice for students and families,” he maintains.

In the classroom, challenges for teachers in the state’s 13th-largest district include mental health support for students, which he says he continues to prioritize at the district level.

The opportunity gap, while not as dire as at ACS, still shows a discrepancy between learning outcomes for Black and white students in BCS, which Jackson argues closes with a different approach.

He says the focus needs to be on individual students rather than all students collectively.

“When we talk about very specifically, each and every student, we are recognizing that every single student individually is important and worthy of our very best efforts. And ultimately, the way that we narrow and close and get rid of achievement gaps is simply by making sure that we’re serving each and every student.”

He says the district is able to share resources across teachers and schools to better reach each student’s unique situation, strength and opportunity.

For Jackson, the biggest challenge facing BCS in the coming year is the quickly growing number of students whose first language is not English.

To address this, Jackson plans to reopen a newcomer center in Buncombe County in 2024-25 modeled after those he toured in Guilford County — home of Greensboro — last year.

Parents could opt in to a newcomer program, where their children would be given a year in an atmosphere curated to those who are just arriving in the United States to acclimate to the culture and processes that may be different than their home countries. After a year, those students would transfer back to the school they are zoned for, Jackson says.

The year ahead

With a full year under his belt, Jackson is in the process of completing the district’s first strategic plan since the pandemic.

He plans to take a draft plan to various school advisory councils — made up of students, parents and teachers — and community town halls in the spring to get feedback on what the district’s priorities should be.

“It’s a continual cycle of listening, learning, leading … and that’ll continue. I mean, that’s who we are as educators and who we are as a school system, [we have a] true commitment to continuous learning, continuous improvement,” he says.

He hopes to improve the district’s relationship with parents, some of whom were vocal at school board meetings throughout the year, criticizing the district for everything from student safety to not including parents enough in its policymaking.

“Our parents feel like not only do they have the right to be involved, but they’re enthusiastically invited to be involved. We know that when a child has the involvement of their parents and guardians with the school system, they’re more likely to be successful,” Jackson says.

Jackson remains overwhelmingly optimistic about the district’s future.

“I have said since the year started that I believe this will be our finest year ever. And as we finish our first semester, I believe that we are well on our way to making that happen. As I walk in our buildings, our buildings feel positive. I see students who are engaged in incredible instructional activities, I see teachers who are working so hard, and who seem to be enjoying the work.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.