Larry and Dot Rice thought they’d found their “haven” when they bought a wooded property on Mills Gap Road in 1974. “This was supposed to be something we could leave to our family,” says Dot. “We’d be able to do whatever we wanted to with it.”

But their hopes were shattered in 1999 as evidence came to light that their well water was contaminated with high concentrations of trichloroethylene, an industrial solvent. Worse still, the Rices learned that state and federal environmental agencies had been alerted a decade before about contamination leaching from the former CTS of Asheville electroplating plant next door (see “Fail-Safe?” July 11, 2007 Xpress).

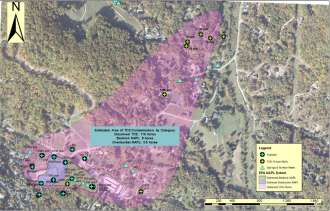

As early as 1990, Environmental Protection Agency officials received reports of possible contamination at the site. The following year, an EPA contractor found “high levels of 1,2-dichloroethene, trichloroethylene, vinyl chloride, and several unidentified organic compounds,” yet no action was taken for almost a decade, and attempts at remediation didn’t start till 2006 (see “CTS Timeline”).

Since then, both the former CTS property and the EPA have become lightning rods for community concern and activism, and meanwhile, progress in cleaning up the pollution has been painfully slow. The soil vapor extraction system installed in 2006 was rendered inoperable by copper thieves in 2010 and was never repaired. Although it had removed some 3 tons of pollutants, the system wasn’t able to address the deeper pockets of TCE in groundwater. And while some affected residents have been connected to city water lines, no further attempt to address the on-site source of the contaminants has been made since then.

With the EPA set to implement a new remediation strategy this year, some residents and public officials are cautiously hopeful that the long-standing issues might finally be addressed. Others continue to lobby federal authorities to hold the EPA accountable for past missteps and speed up the remediation process. This is critical, community activists say, pointing out that even the new strategy is billed as only an interim measure.

In harm’s way

Zip-tied to the front gate in the fence that separates the roughly 10-acre CTS site from the outside world is a small “no trespassing” sign; about 30 yards away, a larger sign identifies the property as a Superfund site. No details are given, and there’s no indication of who to call with questions.

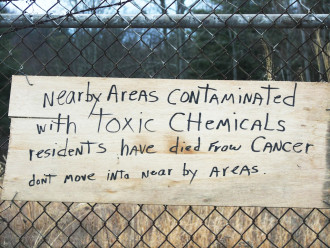

But many warning signs hang on the fence surrounding the Rices’ contaminated spring, which is capped by a mass of plastic sheeting, pipes and a vapor control system.

“A year or two ago,” says Larry Rice Jr., the fumes “were so bad that my children couldn’t get off the school bus.” The former kickboxing champion was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2011. “I’ve lived clean — no bad habits, no smoking — yet I have the lungs of someone who’s smoked for 40 years.”

And while Rice says his doctors won’t go on the record speculating about what may have caused his illness, he blames the water he drank for most of his life. “I have drunk this water by the gallons,” he reveals. “I thought this was good mountain spring water.”

Over the past 15 years, the extended Rice family has experienced a host of health problems. “My husband has a brain tumor and COPD, my son Terry’s had glaucoma since his 30s, my granddaughter has a brain tumor, I’ve had two thyroid tumors, multiple skin cancers on my face, arms and chest,” says Dot. “All of us have muscle aches, stomach aches, headaches, runny noses — even Larry junior’s kids.”

Fortunately, Larry senior and Dot can fall back on his military benefits for their health care. But at a time when Larry junior ’s thoughts had been turning toward retirement, the 56-year-old finds his health issues hampering both his martial arts career and the odd jobs he now does on the side. “I have to go back to work like a 25-year-old man,” he reports. “Not only do I have to change careers, but do it when I can barely work four hours a day anymore.”

Meanwhile, he’s even more concerned about his wife and two sons. “My children are 9 and 10 years old, and they’re asking me, ‘Daddy, are we gonna die of poison? Daddy, why aren’t there any frogs or turtles in the creek?’ That’s heartbreaking for a father.”

Pointing to the empty barrels clearly visible under a pile of debris on the CTS side of the fence, less than 50 yards from his house, he says: “It’s hard to be calm about the situation. They knew all this decades ago, and they willfully left people in harm’s way to live here.”

Seeds of distrust

“If you look at the history of the site, things were known early on by the agencies whom the public puts their faith and trust in that were not disclosed and did not come to light until activists got involved and sort of exposed it,” says Barry Durand, a local chemist who first brought the situation to Xpress’ attention in 2007.

Durand and others say that contradictory or missing public documents and test data, conflicting locations given for the site, a revolving door of EPA on-scene coordinators, and the ponderous pace of official response have continuously plagued the cleanup progress. “If you don’t have accountability at the agency, these things end up happening,” Durand contends. “The mistakes made have not been confronted directly with an eye toward trying to correct them.”

And that, in turn, can lead to deep and persistent distrust, says Lenny Siegel, executive director of the Mountain View, California-based Center for Public Environmental Oversight. “People need to hear about these issues from the regulators rather than finding out about it themselves, knocking on the regulators’ door, and seeing that they’re barely aware of the situation,” he points out. “That creates the high level of mistrust that many of the people around the CTS site have.”

U.S. Rep. Mark Meadows, whose 11th Congressional District includes the site, says the overriding response he’s heard from the community is that “They just want honesty and transparency from the EPA. Past failures have tainted the trustworthiness and reputation of those that are charged with cleaning up the site. So whether there are areas to be concerned about or not, it makes everyone have to question, What is the truth? What’s not the truth? What’s being said and what’s not being said?”

Property shock

Health issues aside, property values are also a major concern for many of the CTS site’s neighbors. In her 2014 book Toxic Communities, professor Dorceta Taylor of the University of Michigan notes that “Property values decline in neighborhoods around hazardous waste sites,” even when the sites are officially deemed safe.

Bob Selz, president of the Southside Estates Property Owners Association, says that pattern has played out in his neighborhood, which sits on a ridge overlooking the CTS site. “We’ve had several parcels of land that were purchased for, oh, $65,000 to $75,000,” he reveals. “They’ve since been sold for roughly $15,000.”

That scenario weighs heavily on residents’ minds, says Tate MacQueen, a local activist and social studies teacher whose home was switched to city water in 2014 after his well was found to be contaminated. “One buys a house with the intention of building equity in it, so you can sell it to finance your next home or retirement. Then suddenly that’s taken from you.”

Siegel, however, says, “If properties are properly investigated and typical environmental responses are implemented, the impact contamination might have on property value is largely reversed. But the regulatory agencies, because property values aren’t part of their job, don’t always do a good job of communicating that.”

Between May 2014 and April 2016, the average selling price for homes in SouthSide Village, another neighboring subdivision, was $358,500, up from $353,500 for sales between July 2012 and June 2014. “Property values have been maintained during the various economic periods of the last 10 years,” SouthSide Village board member Therese Figura reports.

The Rices, however, despair of ever being able to sell their property or escape from the contamination. “If I had the money to move, my family would be out of here rapidly,” says Larry junior, “but it’s kind of hard to just pick up and move” without selling their property. “This is all paid for: We’ve worked hard as a family to pay for this place. And now it’s worthless.”

A matter of disclosure

Like the Rices, Richard Sullivan thought he was fulfilling his dream when he bought property on Pinners Cove Road, about 2 miles from the CTS site, in 2013.

“The day we closed on the property, we drove down to the corner of Pinners Cove and Mills Gap and saw the news crew,” he remembers. “I pulled over and asked the guys what was going on, and they said it was the CTS Superfund site.”

Sullivan alleges that Town and Mountain Realty in Asheville, the seller’s agent in the transaction, never disclosed the potential contamination issues. “I’d like to know any Realtor in the area, specifically that sells in Arden, that doesn’t know that existed,” says Sullivan. “But because I can’t prove they’re lying, there’s nothing I can do.”

Kenny Potts, the Town and Mountain agent who handled the sale, says, “Everyone was under the impression that EPA was handling the cleanup and was replacing well water with city water for the homeowners in that vicinity. We based this on information provided on the EPA’s website.”

Town and Mountain owner Mike Miller adds that under state law, such disclosures aren’t required for land transactions. “My understanding is that Mr. Sullivan bought this lot without seeing it in person, and they had a buyer’s agent from another local firm representing them,” notes Miller. “Mr. Sullivan has brought his issues before the Asheville Board of Realtors’ grievance committee and the N.C Real Estate Commission, which is chartered to protect the real estate consumer, and his complaint was dismissed.”

State law does require property owners and real estate agents to disclose potential environmental concerns in connection with the sale of houses or other structures. But the onus is on the buyer to prove that the sellers knew about the problems prior to the sale. And in any case, says Siegel, the disclosures required by such laws typically “don’t describe what the risk is — they just say there’s a contamination site nearby.”

Miller maintains that he’s often gone beyond the legal requirements in making clients aware of hazardous waste sites near properties for sale. “The mantra at my office is ‘disclose, disclose, disclose,’” he reports. “I know that sounds like a cliche, but for us, it’s about doing the right thing. We preach it all the time, we teach it all the time, and as far as I know, we practice it.”

Town and Mountain, adds Potts, has since created a new disclosure protocol based on information provided by the EPA. “Currently, we and numerous other agencies use the buyer’s acknowledgement disclosure. This form was created by two firms and two local attorneys to address various disclosure issues such as the CTS site.”

To date, no contamination has been found more than about a mile from CTS, and the EPA’s latest plume map does not include Sullivan’s property. But it does show a plume extending in his direction, and there’s no guarantee that properties farther out won’t be affected in the future.

Test anxiety

Last June, four homes on Silk Tree Lane in SouthSide Village came under scrutiny when outdoor ambient air samples yielded higher TCE readings “than the concentrations historically detected in these areas,” according to a report by Amec Foster Wheeler, a contractor hired by CTS to conduct tests and report to the EPA. The subdivision sits just below the site along its western border.

But the Silk Tree Lane residents denied the EPA’s requests to take indoor air samples, and the SouthSide Village Homeowners Association refused to allow additional outdoor tests. Meanwhile, testing last August on the adjacent Powell property showed an even higher reading (13 micrograms per cubic meter), though Craig Zeller, the EPA’s on-scene coordinator, says more recent testing has shown lower concentrations.

“October 2015 and January 2016 ambient air data from the undeveloped Powell property are at or below the screening level,” says Zeller, “and thus would not indicate a need to collect crawl space and/or indoor air samples from the Silk Tree Lane properties.”

Asked about the situation, Figura said the residents in question “had no reason to be concerned, because air testing had been done over six years, with documentation proving there was not a health threat. These residents have lived in SouthSide Village for years and have not experienced any health issues.” The CTS contamination, she continued, “was a shock to many of us, but there were many locals who knew about the issue for years and decided to buy homes in the community. SSV residents have not reported health issues related to the site contamination. Various test results, over 10 years, consistently concluded that the soil and water were not contaminated, and it has been noted that higher concentrations of contamination were east of the site.”

A January 2015 letter from Franklin Hill, director of the Superfund Division for the EPA’s Region IV, stated that “Air sampling to date has not indicated unacceptable risk to human health within the residential area of SSV,” (see “EPA Clarifies SouthSide Village Status,” March 27, 2015, Xpress).

Zeller says Hill’s statement remains valid based on subsequent EPA data, but Siegel cautions that quarterly air samples may not be a good indicator of overall risk. “Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence,” he points out. TCE concentrations in indoor air vary daily, Siegel explains, and outdoors, something as simple as a change in the wind’s direction could affect test results.

“One would need to do sampling every day or nearly continuously to say conclusively that it’s safe,” he maintains. “While there are devices that allow for continuous sampling, the current technology available on the market is expensive and time-consuming.”

Disrupted lives

For the CTS site’s neighbors, the contamination has disrupted daily activities that most folks take for granted. Where the Rices once held barbecues for friends and Larry junior’s martial arts students, he says he’s now afraid to have people over to his house. “Every time someone calls, I have to tell them about the risks of just being here.”

Meanwhile, Dot Rice is simultaneously taking care of her ailing husband and raising her granddaughter’s 17-year-old, whom the mother is unable to care for due to complications from a brain tumor.

And besides the effects of the toxic chemicals themselves, notes MacQueen, “There’s the health impact that comes from anxiety and fear and being angry.”

“It really weighs on you,” says Dot. “You wake up at night — if you go to sleep at all. If they could have seen my husband when we first moved here, what kind of man he was and what he is now. He was wounded twice in Vietnam fighting for his country, but when it came to helping us, it seems like it’s hard to get anything.”

For his part, Sullivan says the presence of a Superfund site near his land brings back a host of bad memories. “I grew up at the Little Elk Creek Superfund site in Maryland,” he reveals. “I lost most of my family to cancers because of that site, which was contaminated with the same chemical. How am I supposed to drive to that stop sign every day of my life and look at that place across the street? Think about what that does to someone’s psyche.”

A brighter future?

On Feb. 11, the EPA officially approved a plan calling for a combination of electrical resistance heating and in situ chemical oxidation, with implementation to begin by this fall (see Feb. 11 Xpress blog post, “EPA Finalizes $9 Million Interim Cleanup Plan”).

The new strategy, says Zeller, is expected to “mitigate, if not eliminate, TCE transport to the eastern and western springs areas.” Nonetheless, it’s still only a stopgap measure. According to the February report, “Final sitewide cleanup is not expected for several years” and will require yet another round of decision-making.

In the meantime, it’s important for local representatives to keep up the pressure on both the EPA and CTS, says state Rep. Brian Turner, whose 116th State House District covers much of Buncombe County.

Asheville City Council member Julie Mayfield says, “I’m hoping that the fact that EPA has initiated and now approved this interim action, and essentially forced CTS to broaden the scope of that action, that they’re finally going to start cleaning up.” Real progress on a cleanup would go a long way toward rebuilding trust between the community and the federal agency, says Mayfield, who is co-director of the environmental advocacy group MountainTrue and also serves on the POWER community advisory group for the CTS site.

U.S. Rep. Patrick McHenry, whose 10th District borders the CTS property, says positive strides have been made in recent years. “Early on, I was alarmed that the communications dynamic between EPA and the community was not focused on the issue of utmost concern — cleaning up the contamination,” he says. Since then, McHenry says he’s worked to improve communication between the two groups and keep remediation efforts moving forward. “My duty is to stand with the impacted constituents and maintain pressure on the EPA, to ensure their full focus is on the cleanup effort. Projected deadlines must be met, and predicted outcomes must be realized.”

MacQueen, however, says, “I ran for Congress in 2014 precisely because our primary representative, Mr. McHenry, has yet to lift a finger on this issue. My objective was to put this issue out for public consumption. I still hold out hope that perhaps he will take a position that’s in keeping with how he’d want to be represented.”

Rep. Meadows, meanwhile, says, “Until the site is cleaned up, and we can verify and double-check that it’s not harming anyone’s health, the jury will still be out. Once trust is broken, how long does it take to gain it back? For some, that’s a longer journey than others.”

Dot Rice concedes that things have gotten “a little better” in recent years, but she’s skeptical that real progress is finally on the horizon. “They’ve talked for years about doing something, but it’s always just talk and more testing.”

Turner, however, says the best way for the EPA to regain citizens’ trust is simple: “Immediately begin work on removal of all contaminants, including the source. If they want extra credit, they should sit down with the Rice family and others affected and find out what they can do to help them.”

Word to the wise

Government officials have gotten mixed reviews, at best, from Mills Gap residents, and for her part, Dot Rice says she’s most thankful for those dedicated neighbors who’ve helped her community bring this issue to light. “They put their lives on hold almost,” she notes. “If we had some EPA employees that were as dedicated as Barry and Tate, they might really be a protection agency.”

And as Asheville continues to attract retirees and other transplants, Rice worries that this could spur additional development around some of the county’s many inactive hazardous waste sites (see “Hidden Hazards,” Jan. 11, 2011, Xpress).

“A lot of folks think it’s not going to affect them, but you never know what’ll happen,” she observes. “It’s happening in our community, and if we don’t do anything about it, it can happen to yours, too.”

CTS issues need to be resolved this year.

CTS Townhall meetings on video:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLN1NFyDWZWzeIdsOL0OiTS2AS-SIPpZVM

Looking at the timeline box would explain why pollution problems persist in North Carolina. It took NCDENR 12 years to finally decide to collect water samples (notified in May 1987…sampled water wells in July 1999). Ore Knob mine still belches mine waste into the waters of the New River in Ashe County. Seaboard Chemical still leaks dioxane chemicals into Greensboro’s new Randleman Dam drinking water. Duracell Battery mercury that leaked from the Lexington NC plant still contaminates High Rock Lake. Do not eat the fish if ye are pregnant say the posted signs there. At least Walmart finally cleaned up the Bleachery Blvd site in Asheville. Maybe they will buy this CTS site for another store location and put their millions to use on doing what NCDENR has been able to force CTS to do. CTS=chemical toxic stuff

Seaboard is a toxic dump. When you pump & dump chemicals into unlined holding pond(s) and then pump & clean because you know the inspectors are coming onsite…. you know you are doing wrong. These guys were in the know and knew when inspectors were scheduled. Corrupt? Yes. Would the previous owners drink the water? No! But they’ll live in big houses and leave a legacy for their kids /family built on the backs, colons, breast, livers, lungs of people that worked there and live in the community. Cancer statistics in surrounding areas – watched my neighborhood develop so much cancer that I stopped drinking the water. How do you have cancer in every single home unless the common denominator is water, especially when they’re all well water?? Holding the toxins down – Randleman Dam – maybe the only answer, but there has to be a better way.