Sometimes you’re asked to help plan a reunion. Rarely, if ever, does it result in a $50,000 grant. But this was the case for Trey Adcock, UNC Asheville assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies and director of the American Indian and Indigenous Studies program.

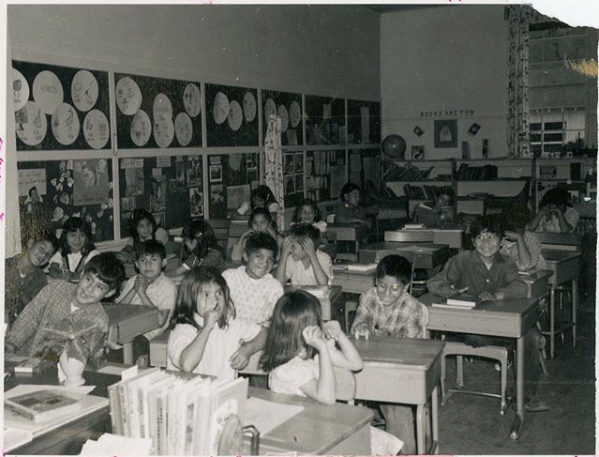

An enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation, Adcock was approached last year by Eastern Band members from the community of Snowbird. As former students of the now defunct Snowbird Day School, the group hoped Adcock might assist with organizing and reaching out to fellow former classmates. Since the school’s closing in 1965, no such reunion had ever taken place.

Adcock agreed to facilitate the gathering. But in the early stages, he quickly recognized the chance to host something far greater than a mere get-together. If done correctly, members of the reunion could fill in some of the gaps of Cherokee history.

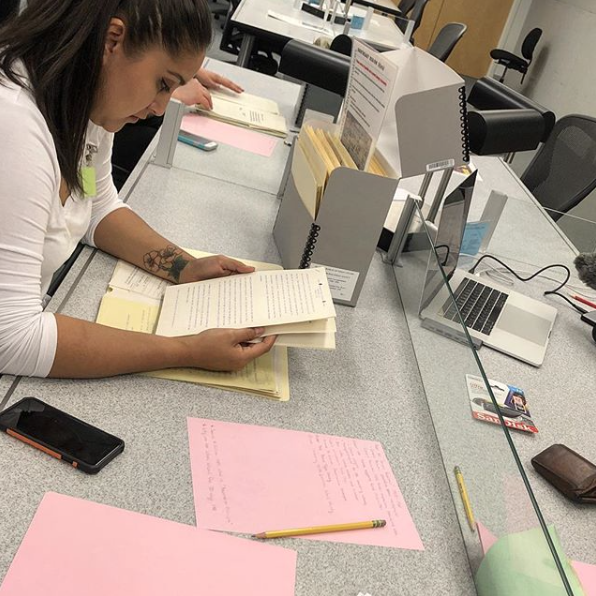

In late February, UNCA announced that Adcock was one of seven national recipients of the White Public Engagement Fellowship. With the $50,000 grant, he and a team of students and colleagues began work on a project that they believe will take a minimum of two years to complete. The undertaking involves collecting, preserving and digitizing the stories of the Snowbird Day School through oral histories and archival research.

“We are building an online archive,” Adcock explains. “The goal is to hand it all back over to the community once we’re done.”

The legacy of language

While no single narrative has dominated the 15 oral histories conducted thus far, a pair of names has come up again and again: Albert and Louise Lee. The couple arrived to Snowbird in 1949. Albert Lee was brought in as the day school’s principal. Meanwhile, Louise Lee was hired on to teach. The husband and wife team remained at the school until it closed in 1965.

According to Adcock, the Snowbird community is unique in that a large portion of its elderly residents still speak their native language. He partially attributes this situation to the Lees, who allowed the children to interact in both English and Cherokee.

This was far from standard practice for most day school operations, notes Adcock. In the 1860s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began establishing these institutions; one of the bureau’s primary goals was assimilation. Gen. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlise, Pa., perhaps best exemplifies the mindset of those in charge. His motto was, “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

Gil Jackson, UNCA lecturer in modern languages and literature, is a former student of Louise Lee’s. He also manages the oral history component of the Snowbird Day School project, which he conducts in the Cherokee language. Like Adcock, he praises the role the Lees played at the day school. Their approach, he states, “was very unusual. I’m sure they were aware of the assimilation policy that the government had, but somehow or another they ignored it. I think they appreciated the language and the culture.”

UNCA senior Dakota Brown, one of the students participating in the project, echoes Jackson’s sentiment. “The Lees came in with the idea that they were going to educate, but not necessarily assimilate,” she says. The result, Brown points out, is evident in the community to this day. There is a reason, she says, that Jackson is able to conduct his interviews in Cherokee. This very fact, she continues, is a direct result of the school’s legacy.

Humor, pain and everything in between

As a history major with a minor in American Indian and Indigenous Studies, Brown’s role as a researcher is a natural fit. But in addition to her academic credentials and interests, she is also from Snowbird. In fact, her father, uncle and grandparents all attended its former day school.

For Brown, one of the main appeals of the project is its specificity. So often, she says, Native American history gets reduced to two acts: first contact and the subsequent removal out west. “People don’t usually talk about these little small community day schools and the experiences had,” she says. But it is in these types of stories, she adds, that a more nuanced history is revealed.

Talk, however, can prove tricky. Brown recently interviewed her grandmother, Frieda Brown-Rattler, for the project. In 1954, Brown-Rattler was one of the first students from the Snowbird community to integrate into the nearby Robbinsville public school system. During their conversation, Brown notes, her grandmother was reticent to discuss the transition in great detail. “She didn’t want to say anything too negative,” Brown explains. “She said some students were very receptive and nice to her, and others were not.”

In Brown’s view, this reticence is par for the course. “You have to listen and be receptive to what information they’re willing to give you and realize this isn’t your story,” she says. “This is their story, and you have to allow them to share what they’re willing to share and not push too much.”

Along with reticent subjects, there is also the issue of memory itself. To combat its elusive nature, Jackson regularly brings old photographs to individual and group sessions. Since launching the project, the UNCA research team has gathered over 300 images from the former day school. Most of these, notes Adcock, were taken by the Lees.

Jackson says the stories run the gamut from humorous anecdotes to painful encounters. One participant recalled recesses spent playing in the nearby creek. Another remembered working in the lunchroom. A few have noted unpleasant run-ins with substitute teachers who objected when students spoke Cherokee.

For Adcock, it’s essential that the project capture the full range of experiences. “There is not one story that has come to the forefront,” he says. “I think it’s a collection that showcases a complicated history around assimilation and maintaining culture.”

‘The story of Appalachia’

Come August, former Snowbird Day School students will finally hold the official reunion that inspired the project currently underway. The gathering will give the team of UNCA researchers a chance to present some of their findings to the group. This will be a significant moment for Adcock. “To me, the work doesn’t really have value unless it has value to the community,” he says.

In the meantime, the crew continues its dive into state and regional archives, as well as its ongoing efforts to capture personal histories. But the project’s end result, says Adcock, is not set in stone. Nobody, including Adcock himself, knows where the information might lead them.

Yet Adcock’s intention is clear. The project is meant to give voice to those previously silenced through assimilation and forgotten histories. In sharing the personal accounts of these alumni, Adcock hopes to break many of the stereotypes still held by non-natives. And by breaking the stereotypes, he aspires to forge a deeper connection between communities. “It’s not just a Cherokee story,” he explains. “It’s a story about segregation and desegregation. And that is part of the American story. And I think that’s an important story that needs to continue to be told.”

After some additional thought, Adcock adds, “It’s also a Western North Carolina story. I mean Snowbird — you don’t get more remote than Snowbird. This is a rural population, a poor population. It’s the story of Appalachia.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.