By Kayla Guilliams

Every year, several waves of migrant workers with agricultural work visas come from Mexico to lend a hand on Tracy Taylor’s Christmas tree farm in Watauga County. The first group arrives around March, ready to help with initial fertilization and seeding.

However, those initial workers are experiencing a much different season than normal at Stone Mountain Farms. With the COVID-19 pandemic continuing to spread across North Carolina, Taylor and her crew are having to adjust to a new, more cautious way of operating.

“I am scared,” says Taylor. “But confident that we’re doing all we can to stop the spread.”

Feeling vulnerable

As of June 16, Western North Carolina has 15 cases of COVID-19 among farmworkers, all at Grouse Ridge Tree Farm in Ashe County, according to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services. A total 108 farmworker cases have been reported throughout the state — nearly double what had been reported just a week earlier.

Marianne Martinez, however, says these numbers don’t necessarily tell the whole story because they only reflect cases confirmed by testing. Martinez is the executive director of Vecinos, a Cullowhee-based nonprofit that provides free medical care to uninsured and underinsured farmworkers across eight WNC counties.

“Testing is still extremely limited, especially outside of Buncombe County,” says Martinez. “I’ve been working with the health departments for weeks to get tests, but the cost of running them is prohibitive.”

While free community testing for COVID-19 is available in Sylva, a regional hub for much of rural WNC, Martinez says it’s inaccessible for the vast majority of farmworkers who lack personal transportation. Another obstacle to receiving a test in Sylva is mandatory online preregistration.

“If you don’t have access to a computer or the internet, how are you going to do that?” asks Martinez. “There are a lot of barriers to testing, even where there are testing sites.”

This lack of testing concerns Martinez because of how vulnerable migrant farmworkers are to the coronavirus. As “congregate living settings,” migrant farmworker camps have been listed as high-risk locations for virus transmission — not just by local counties throughout WNC, but by the NCDHHS and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“If you look at a lot of migrant camps, they live, say, six men to a motel room in bunk beds. There’s no social distancing.” explains Martinez. “So if a farmworker gets infected, he’s going to spread it to six of his roommates, and they’re all going to get infected. There’s no way to stop it at that point.”

Safe travels?

North Carolina’s first wave of migrant farmworkers this year arrived at the N.C. Growers Association office in Vass, located in the state’s Sandhills region, in early March. The workers came to Vass from the travel hub of Monterrey, Mexico, on 40-person buses. Their temperatures were taken before leaving the city, as well as at the U.S. border, according to reporting by NC Policy Watch. Routine COVID-19 testing for incoming workers wasn’t conducted and isn’t yet available.

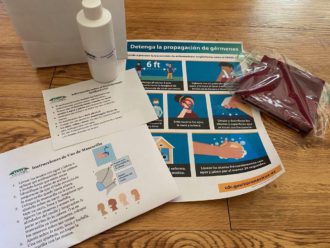

Upon arrival, the workers’ health was screened, and they were given Spanish-language information provided by the CDC regarding COVID-19. From there, they went to farms across the state. Taylor’s workers arrived at her farm around March 14.

It wasn’t until March 26 that NCDHHS released official recommendations for farms to prevent the spread of the disease among migrant farmworkers. These voluntary guidelines encourage growers to provide sanitation supplies weekly, make COVID-19 information available in Spanish and spread beds in housing at least 6 feet apart.

Local county agricultural extension offices have helped WNC farms follow these guidelines, says Jim Hamilton, extension director for Watauga County. He says his office has provided translation support, as well as cloth masks for workers and sanitation supplies such as hand sanitizer, bleach and sanitizing wipes.

Steve Duckett, extension director for Buncombe County, says his office has also been providing supplies and education to the farms and several hundred migrant workers in the county. “If I had to boil it all down, we’re kind of performing one of our age-old roles in a new way,” says Duckett. “We’re kind of being that resource clearinghouse for producers.”

Providing personal protective equipment such as masks has been a priority for these offices because the supplies are needed by employees who work with chemicals. When high demand at health care facilities created PPE shortages, Hamilton says, the N.C. Agromedicine Institute helped get masks to farms that were running low. Duckett adds that the federal government also reserved some masks specifically for use in agriculture.

The need for PPE to reduce chemical exposure will be even more prevalent later this growing season, Duckett continues, which could cause problems if the mask supply chain remains constrained. He notes that masks aren’t as much of a concern in and around Buncombe County as in other parts of the state because many local farms use organic practices.

Disseminating Spanish-language information about health care has been another focus for both county offices and Vecinos. Martinez says her organization has been prioritizing information outreach since the start of the outbreak.

“A lack of general health education coupled with misinformation, in particular for this community, has been a major challenge,” said Martinez. “Our community health workers from day one started going out to migrant camps and giving reliable sources for information in Spanish and spreading the information we knew at the time. And we have continued this outreach over the phone.”

Business as unusual

Taylor says for her workers at Stone Mountain Farms, she is taking all precautions, following all guidelines and supplying all materials necessary to keep them safe. Those steps include liberal supplies of hand sanitizer, wipes and disinfecting spray, and twice-daily temperature checks as they clock in and out from the farm.

Many sanitation measures, Taylor points out, were in place before COVID-19. “Why wouldn’t you do this even prior to the pandemic?” she asks. “Who would want their worker to get sick or be unsanitary? Not me — they’re family to me.”

What is new for Taylor is making sure that when her workers leave the farm, they are social distancing and taking precautions. “They have masks, and we tell them all the time that when they go to Walmart or the grocery store, we want them to change clothes,” she says. “We’ve given them extra jugs of laundry detergent, and I think it’s smarter for me to give them, you know, $50 in laundry detergent than it is for me to take the chance of one of my guys getting sick.”

Roberto, a migrant farmworker with an H2-A agricultural visa working in WNC, agrees that this season has been different from any other. He provided a statement to Vecinos in Spanish; the nonprofit translated his words and agreed to use only his first name for privacy.

“I’ve personally seen a radical change in how we see things and think about them since the government has deemed us essential workers. That puts us in a position of risk, not only on the local level, but on the international level as well,” Roberto says. “We are vulnerable workers, but we are still deciding to contribute to the United States with our essential and basic work for the well-being of others.”

But Roberto notes that his actual duties on the farm haven’t changed much since COVID-19 began. “We’ve continued to work as normal, albeit with a lot of restrictions like using face masks and hand sanitizer as preventive measures,” he says.

Tough case

Martinez emphasizes that COVID-19 prevention is just half of the issue. Farmworkers who aren’t working through the H-2A program often lack access to health insurance, while those with visas have access to highly subsidized rates but often still choose not to participate due to cost.

“As a farmworker, paying for it takes away from what you can send back home,” Martinez explains. “I could pay for health insurance each month, or I could use that to send my children to school back home.”

And even workers with insurance may not seek primary care if they get sick. Martinez says most farmworkers don’t ask for time off to get help because they don’t want to lose pay, and for those who lack personal transportation, getting to clinics can often be a challenge.

Cultural incompatibilities also pose an obstacle to care. According to a 2017 study published in the Journal of Agromedicine, many migrant farmworkers are distrustful of Western medicine because of their unfamiliarity with local health care systems and differences in how diseases are treated. Martinez says this is true in WNC as well.

“A lot of our farmworkers come from very small indigenous communities where their health care ways are vastly different than what you encounter in Western medicine,” says Martinez. “As far as primary care goes, that’s a major barrier to care.”

Despite these barriers, Taylor says that if any of her workers were to start showing symptoms of COVID-19, they would get paid time off, be quarantined and receive immediate access to the care they needed.

“We have workers’ compensation, so they would get two weeks paid, and as far as health care, they don’t have any out-of pocket-expenses,” she explains. “And if for any reason there was an issue, it would be out of my pocket, because they would never go without health care. That would be ridiculous.”

Taylor’s farm has yet to see any cases of COVID-19. However, she did have a scare when two workers started coughing and sneezing toward the end of March.

“We told those workers that they had to stay home until we figured out what was going on, and within three days they were fine — it was just a cold,” says Taylor. “But I’m not going to lie: We went hard and we were superserious about it. I think that it was our test, because we immediately acted upon it and had a plan on if something were to happen.

“I think a lot of our response was because I was educated from all the paperwork that’s been sent to me by various different departments in the state and county,” Taylor continues. “Because we had been reading up on it so much, we’d like to think we did everything right.”

Into the unknown

More waves of workers are set to come into WNC for the fall harvest season, especially to areas like Henderson County that have a lot of apple farms, says Duckett with Buncombe County. This influx will make farms and housing even more crowded, and having enough supplies and information available will be even more of a challenge. The fall will also raise concerns about new workers bringing COVID-19 to these farms — especially if testing is still not routine for incoming workers.

“The future is very scary to me, No. 1 because as a society, we’re still learning about what COVID-19 is,” says Martinez. “We still don’t really know what we’re dealing with, and that terrifies me.

“In the future we will be doing testing, we will continue to do health education, we will continue to do telehealth,” she continues. “We’re just taking it day by day and trying to be as proactive as possible.”

Taylor also expresses concerns about the future. She implores her fellow growers, in WNC and beyond, to prioritize the well-being of their workers.

“I know we all have to continue working, but what’s more important: the almighty dollar or your employee?” Taylor asks. “For me, it’s my employee. I have to go with them every time. The trees will still be there. I might not make all that money this year, but I’ll sell it next year. The employees have to come first.”

Kayla Guilliams is an experienced environment and science writer based in Chapel Hill, NC. She is currently studying to receive her BA in Environmental Studies with minors in statistics and journalism at UNC Chapel Hill, and will start coursework for her MA in Environment and Science Journalism this fall. You can view her portfolio here.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.