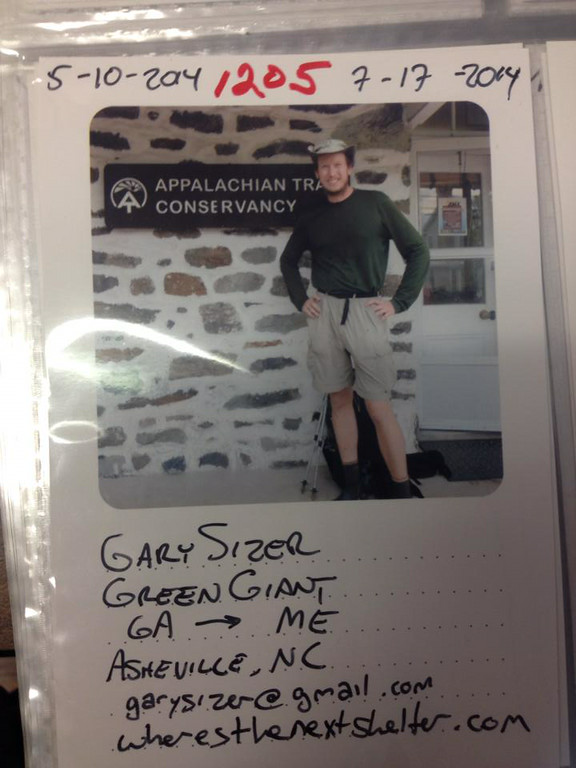

“Starting tomorrow, I live outside,” wrote Gary Sizer on May 9, 2014, his last night in the comfort of his Asheville home.

The next five months of Sizer’s life were spent on the Appalachian Trail, a roughly 2,000-mile trek from Georgia to Maine — a hike he describes as both beautiful and brutal. After walking two months and around 800 miles, in the middle of Virginia, Sizer developed nerve damage in his feet.

“Just agony in every step,” he says. “Even just standing was like somebody stabbing me in the foot. But my thought at the time wasn’t, ‘Oh, I should quit.’ It was, ‘Oh, I should rest a few days so I can keep doing this.’”

Since its initial construction in 1937, 15,524 people are said to have completed the thru-hike of the A.T. — “2,000-milers,” they’re called. Inspiration behind embarking on such a physically and mentally challenging journey varies from person to person, but deep down it satiates core human needs for renewal and a reconnection with nature.

Sizer has never been a quitter, and he certainly wasn’t green to spending long days and nights outdoors. The first time he heard about the trail was in the early 1990s while serving in the Marine Corps in Washington D.C.

“My immediate reaction was, ‘Wow has anybody ever done the whole thing? Because … I’m going to do it,’” he recalls. “It became one of those dreams.”

Some 20 years later, Sizer and his wife, Katie Farrar, were cramming the last of his gear into their car with Georgia on their minds.

“We did the first mile together,” Farrar says. “It was raining and pouring. It was kind of weird knowing that, ‘OK, that’s it.’”

The couple said their goodbyes in the rain, then she turned around to walk back to the car, driving home to Asheville alone. For the next two months, while Sizer made his way north, Farrar visited him nearly every other weekend. But once he reached mid-Virginia, it would be just phone calls and photos from then on.

Taking on the challenge

Over the course of 700 miles, Sizer — now under the trail name Green Giant — had been hiking with Lemmy, a 23-year-old former soldier in the Israeli army who dreamed of being a cartoonist. The two became close, and Lemmy became part of Sizer’s trail family.

But as pain from nerve damage worsened, Sizer told Lemmy, “‘Hey, I don’t think I can keep up with you; go on without me.’” As Lemmy went ahead, Sizer realized this was his first time alone on the trail — “no friends, out in the middle of nowhere, in pain, suffering. That was one of my lowest moments.”

The next day, he walked to a road and hitchhiked to the nearest town.

“I didn’t think I was going quit,” Sizer emphasizes. “I thought I was going to be unable to finish — big difference. When you quit, you’re like, ‘I’m done with this; this is stupid.’ But I was like, ‘Wow, you know, my body is not going to let me do this.’”

And after so many years carrying the trail as his dream, being unable to finish was a depressing thought.

“I’m in town, I’m soaking my feet, I’m crying into my beer,” Sizer recalls, when he gets a call from his wife, who was relatively nearby visiting family. “Every time I hit a low point it was without exception a phone call with her that brought me back.” After listening to his woes, Farrar told him it was OK if he wanted to quit. Sizer says he doesn’t “know if she was using reverse psychology on me or what, but once I heard those words, I got over that barrier. She knows the inside of my head better than I do sometimes.”

After Sizer visited a doctor and rested his feet for what hikers call a “zero” — a day of no forward progress — Farrar picked him up and drove him to meet up with his trail family, a two-hour drive from where he had stopped. But it wasn’t long, another 400 miles, before Sizer ran into his next obstacle: Lyme disease. At first, he didn’t realize what it was — fatigue, aches and pains, flulike symptoms and a severe lack of motivation.

“At the time, I was averaging 20-something miles a day,” he explains. “And as I got sick, it started dropping — 15, 10, 5, and then [sitting] and not [doing] anything all day.”

Once again, Sizer knew he was slowing down his trail family and told them to hike on without him. He’d get over his cold and catch back up, he thought. But as his sickness worsened, he realized he was falling farther and farther behind.

“One night, I’m sitting in a shelter in Pennsylvania all by myself — there was no one else there, which is kind of rare on the A.T.,” he continues. “It was starting to get dark out, and I saw a headlamp coming up the trail. This guy came up and introduced himself as a local. He wasn’t a thru-hiker, but he lived near the trail. And he told me, as a hobby, he hikes onto the trail whenever he can with a backpack of candy bars and sodas — they call it trail magic. He says, ‘I’m just out looking for hikers to give stuff to. What’s your favorite candy bar?’”

The two men sat down by the shelter, and while Sizer snacked on Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, they began to chat. “He gave me his phone number and said, ‘If you ever need anything while you’re in Pennsylvania, give me a call.”

After another few days struggling with symptoms of Lyme disease, Sizer seized that opportunity for help.

“He met me on the trail, took me to his house and … said, ‘You stay here as long as you need to to recover.’ At the time, I still didn’t know what was up; I just thought I was ill, but on the third day he took me to the doctor in town, and I got diagnosed. I was actually happy, because I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s something we can treat! I’ll be back on the trail.’”

That kind of hospitality, Sizer says, “really restored my faith in humanity. There’s just really good people out there, and it just seems like the A.T. — the whole length — is just a magnet for goodness.”

The trail is calling

But why does the A.T. call to so many — thousands every year — from every corner of the country, even around the world?

Windy Gordon, psychology professor at Western Carolina University, specializes in the cognitive benefits of nature. “When you read the tales of people who take on long-distance anything — kayaking, cycling, hiking — I think that the explanations are as various as the people that take them on: ‘I need a change,’ ‘I was ready for a challenge,’ ‘I need to restructure my entire value system,’” he explains. “I think the opportunity for those challenges reaches out to lots of people — and lots of different people.”

Sizer’s reasoning was simple: He loves the outdoors.

“People are always talking about, ‘Well, why did you do it?’” he says. “Like saying, ‘I need to find myself or whatever.’ I just love hiking. I love being outside. Whether it’s been four days or four weeks, I just want one more day. Just give me one more day out there.”

In spring of 2014, Sizer’s wheels began turning. The trail was on his mind. Within ten minutes, he emailed his boss announcing his departure from the company. It suddenly became apparent that the timing was perfect, and he was ready. His dream of “always one more day” was coming true.

And even after 153 days spent in the wild, May 10 to Oct. 9, it still wasn’t enough. “I think I have a problem,” Sizer says, laughing. “So I wasn’t trying to solve any problems in my life or find myself; I just wanted to be outside for as long as possible.”

Though Sizer’s “one more day” mentality isn’t always the case. Many find themselves drawn to the trail as a way to rearrange certain aspects of their being — hoping the A.T. will be a cure-all for finding a new perspective on life.

Henry Wasserman is one of those people. The 58-year-old self-described “conservative Republican Bible-thumping NRA member” living in Pompano Beach, Fla., has never been backpacking before in his life. He is planning to begin his northbound hike in mid-March or early April.

While hiking a portion of the trail in Georgia several years back, he ran into a woman in her late 60s and asked if she needed a ride into town.

“No, I’m going to Maine,” she replied politely.

“That was when I first went, ‘I need to look into this,’” he says.

Monitoring market trends for 34 years as a financial adviser, Wasserman wants out — and he’s experienced his fair share of hardships too. His father died when he was 2, his mother when he was 15. He says he was raised by “the Angels,” bikers, out in California. Wasserman has been married four times — divorced four times — and is 19 years clean of a 30-year drug addiction.

He says he hopes to start everything over when he reaches Maine. To him, the trail is an opportunity to reflect over his life experiences and make changes — even if he hasn’t pinpointed what those changes are quite yet.

“Anytime I’m in the woods, I’m at peace,” he explains. “There’s just something about being in the woods — being surrounded by trees and nature. I’m looking forward to that connection.”

Natural rejuvenation

And that feeling isn’t exclusive to Wasserman — or Sizer — or anyone else.

“Immersing yourself in natural environments can have immediate, very real, cognitive and affective benefits,” says Gordon. While most people think it has some sort of back-to-roots, human-nature origins, it’s more than that, he says.

“Think about how aware you are of just the natural variations in weather,” Gordon explains. For most of us, that awareness is minimal, but on the A.T., “you become intimately reaware of the actual fluctuations of light and temperature [throughout the day, weeks, months]. That awareness is an alternative to the overwhelming cacophony of media and phone calls and other distractions.

“And as you become more aware of the natural conditions around you,” he continues, “I think it relieves that distracting, fatiguing, stressful onslaught that we all experience every day. I think that would be therapeutic even if you weren’t in a bad place — to re-immerse yourself in feeling the natural movement of the day.”

Research on this topic has to do with attention, Gordon says. “If I ask you to engage in a task that demands lots of your attention — attention [turns to] fatigue. … Even a very brief exposure to a natural environment [allows] you to feel recovered and refreshed.”

Nature’s ability to rejuvenate and relieve stress holds roots in key components of effective cognition, Gordon explains. It must be “an alternative from your daily existence, a place you intend to be. It must fill your awareness, and it must be fascinating.” These elements are “almost invariably present in natural environment, … perhaps making you more able to attend to your own feelings, your own values, your own beliefs.”

Wasserman, for example, realizes he will face many challenges over the next several months, admitting he’s about 40 pounds overweight and “about as green as green can be to this.” But quitting his job, selling his home and hiking the A.T. is “kind of a life-transition choice,” he says. “[It] is going to be the happiest day of my life — scariest, but happiest.”

Transformation might not be as easy or as instant as he expects, Gordon cautions. “You don’t leave your crazy, corporate world and suddenly have a Disneylike life with music in the background. The first week or two on the trail, especially for people who aren’t experienced, is pretty brutal.”

And yet, “clearly he has some reason to believe there’s something out there on the trail that’s worth it — even if the worth is in what isn’t there,” Gordon says. “Sometimes the wilderness may be appealing because of what it isn’t. So when I immerse myself in this world where the things that are stressful aren’t present, only later do I begin to benefit from the things that are present.”

All about the people

Wasserman describes most of the people he’s connected with in preparation for the trail as “old hippies wanting to get back to nature. And I’m on the other side of that. It just seems more of a Grateful Dead thing than an Alan Jackson kind of thing.”

Sizer, however, remarks that during his five months in the woods, he saw all kinds of people — in other words, it’s not just “a Grateful Dead kind of thing.”

Thru-hikers are “the most fascinating group of intensely motivated weirdos you could ever hope to meet,” Sizer explains, laughing. “One of the groups I hiked with was a father-and-son team: dad was 65, son was in his 30s. I met women in their 60s, women in their 20s, children, teenagers, kids of every age. There was a mom out there who had three kids with her doing a 400-mile section-hike, and the youngest [with her] was 3.

“You’ve got drunks and drug users and bible bangers and kids just out of college,” he continues. “It’s like a festival. … So the mix of people you have to start with is just amazing, just so diverse. And everyone has something in common — they love the outdoors, and they’re all extremely motivated and focused.”

But hiking the A.T. wasn’t always such a social affair. Morgan Sommerville, director of the Georgia, North Carolina and Tennessee Regional Office of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, finished most of the trail back in 1977 with a few friends.

He began his hike on March 15, which was “shockingly early for 1977,” he explains. “Most people started around April 15, so I was at the head of the bunch. I don’t think I saw anybody else on the trail, other than the group I was hiking with, until I got to Shenandoah National Park.

“And that wouldn’t happen today,” Sommerville continues. “I don’t like to think of it as a party,” but the modern-day A.T. experience “is certainly social.”

A popularity problem

And increasing traffic could mean trouble for the trail.

In 1977, the A.T. was much steeper — and a bit shorter, as, for decades, volunteers with the ATC have worked to redirect the path, both reducing trail steepness and connecting the dots between well-known scenic sites. With occasional sweeping views of valleys below, the relocated sections help hikers avoid a monotonous five to six months in “the green tunnel,” the parts of trail where up, down, left, right — every direction is shades of green. And whereas hikers in the past struggled up sections with a steep and strenuous 40 percent grade, the A.T. of today averages around 9 percent.

Working with the ATC or their local A.T. clubs, more than 6,000 volunteers look after the trail on a day-to-day basis — taking care of small projects like protecting the path from erosion, tending to the wooden shelters and cutting back vegetation, as well as larger needs like trail construction, redirection and water management.

Nowadays, both hikers and the ATC are beginning to see a huge problem with overcrowding. “After A Walk in the Woods [by Bill Bryson] was published, people attempting the thru-hike went up by 60 percent,” Sommerville says. And with a new movie on the way based on the book, starring Kristen Schaal, Nick Offerman and Robert Redford, the ATC is worried that increased numbers will cause mass overcrowding at the 250 or so campsites and shelters built along the trail.

“We want to welcome new people to the A.T.,” he says, “We hope they’ll love it as much as we do, but we also want to keep the A.T. a wonderful, natural place. So there’s got to be some sort of sweet spot there that we haven’t figured out yet.”

With 2,189.2 miles of trail, it’s not that there isn’t room. The challenge is mainly that “the bubble,” or the mass of hikers starting around the same time and place, needs to space out. “If all [2,500 of them] start in Georgia in the springtime, that’ll cause a problem. If we can somehow persuade them to spread that start date or location out, then there’s no issue. There’s plenty of capacity on the trail to handle that,” says Sommerville.

And what would happen if 2,500 or more hikers started at Springer Mountain about the same time?

“There’s limited camping available,” he replies. “There’s places that are good for campsites and places that aren’t. If you look at the existing good places there are to camp, we know how many people they will accommodate. If more than 50 people start on any given day, the campsites are likely going to be over capacity, and that will result in crowding, damaged vegetation, possible unsanitary conditions.”

This problem is especially prominent in the South, because although an estimated 2,500 hikers attempted the northbound trail last year, only 1,267 showed up at the halfway mark in Harper’s Ferry, W.Va. Past that, just 644 checked in at Mount Katahdin, the final summit.

Coming home

“I had really mixed feelings crossing the [state] line into Maine,” Sizer says. “On one hand, there’s this sense of achievement. I took a selfie and posted it on Facebook — you know, like, ‘Walked to Maine! Mind blown!’” Sizer laughs.

“But at the same time, there’s this kind of gentle, nagging sadness,” he continues. “You know, the most fun thing I’ve ever done is almost over.”

And although the trip begins wrapping up, the southern part of Maine is “the most physically challenging part of the trail — the steepest mountains, the deepest mud, the slipperiest roots, the sharpest rocks,” Sizer says. In mid-September, temperatures start to cool, and hikers expect that.

But that year, there was “a particularly severe, unexpected cold snap … and a lot of us didn’t have our proper cold-weather camping gear yet. We were expecting to pick it up in the next town, or whatever. We’re getting physically beat down every day, mentally beat down because the terrain was reducing our mileage from the high 20s to single digits.

“So think about this,” he suggests. “You’ve just spent the entire summer waking up every day and either meeting or surpassing every goal you’ve set for yourself. You’re riding on a natural high, and you just feel unstoppable — every day, just nailing it. And then you get to southern Maine and … you start to feel like a failure. It starts messing with your head.”

Sizer remembers a fellow hiker saying, “Well, I told my friends I was going to walk from Georgia to Maine. Technically, I’m in Maine. I guess I can quit here, and that’s still a win, right guys? Back me up on this!” And some hikers, his friends, did quit, he remembers.

“You’re in the most beautiful place you’ve ever been, but you’re miserable … and you just start falling apart. Crossing that state line? Not quite as happy as crossing into North Carolina.”

And then, just as suddenly as it began, the adventure is over.

No more ice cream parties with Bill Ackerly, a man living 25 yards from the trail who churns ice cream and lets hikers camp in his yard. No more white blazes; no more blue blazes. No more green tunnel. No more trail family — Lemmy, Voldemort, Ninja Mike, Two-Pack.

The weird thing is, Sizer says, the trail “starts to mess with your concept of time. You stop caring what day it is, because it doesn’t matter. … Distance starts to replace time. If you ask any thru-hiker when something happened, invariably they will tell you where it happened and not when. ‘Whens the last time you saw Lemmy?’ ‘Pennsylvania.’ ‘When did you see that bear caught in a bear trap?’ ‘New Jersey.’ ‘How long has it been since you’ve showered?’ ‘Uh, Rangeley.’”

Part of that, he says, is because “you’re always moving in one direction. And when you think of yourself as being stationary and the trail moving under you, it moves in the same way time does. The unknown stretches out before you, it arrives, and now it’s behind you.”

Aftereffects

Coming back into society, things aren’t quite the same.

“A lot of people who read about the trail don’t take into consideration that it’s very jarring going from your normal, everyday life to living in the wilderness — but you get used to it,” Sizer explains. “So used to it, in fact, that when you come back to your life of cars and electricity — it’s a little bit weird. It’s a little off-putting.”

Getting back home, even a visit to the grocery store “assaulted [his senses] — bright lights, colors that aren’t green, so many people making noise. It’s a little stressful.”

While on the trail, Sizer explains, brief visits to civilization are strange but good. “You get to wash, grab a beer, eat a burger, but then you get back into the woods and you’re like, ‘Oh good; I’m home again.’ You start to feel like that’s where you belong.

Coming home is the strangest feeling, he says. “Somebody asks me the last time I got my haircut, and I say, ‘Uh, Asheville.’ Oh wait, I’m still in Asheville. You start to wonder, ‘How long ago was that?’”

Post-trail depression can set in as hikers leave the freedom of the wilderness to return to their structured roles in society.

“The wilderness? It doesn’t cost much,” Gordon explains. “When you re-enter the world, one of the first things you have to do is worry about putting gas in your car or paying your cellphone bill — whatever.” Such things “are just immediate stressors.”

And even the number of choices we have in modern society can cause stress for returning thru-hikers, he continues. “Food [on the trail] is basic; it’s simple — it’s just about the calories. Once you get back here it’s like, ‘Well, are we going to eat Ethiopian or Italian or American?’ And we add all these other levels of decision-making — it just must add some psychological challenge … upon trying to reintegrate.”

The best treatment, both Sizer and Gordon recommend, is to get back outside — even if just for a moment. Feel the breeze. Take a hike. Lie in the grass. Watch the sun set.

“All I’ve done for the last three months is think about the trail,” Sizer continues. “It’s in me. It’s in my head. I can’t get away from it. It’s something that I carried around as a goal for so many years. And having done it and being able to look at the scale of what I did on a map really gives me a sense of empowerment. I really feel like anything from this point on that I decide to do, I can do. I now have an example I can look back on and say, ‘Goddamn, you can really do some amazing things, can’t you?’”

Web extra: On the trail, Sizer took a photo of himself every day to show his changing appearance over 153 days. Watch below:

Great article!

-Slick (2013)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUXDqJTjkyM&index=1&list=FLbxK2mpum8D5m3tEvdssSwA

Thanks! And cool video. Can’t watch the whole thing at work, but it looks like you had fun!

This was a terrific interview with a recent thru-hiker and I appreciate how well-researched it was, including relevant details about the trail and forecasts for future use. I also enjoyed the academic comments from WCU’s Windy Gordon about just why it’s so important to the human psyche to find and experience wild places. The writer did a great job weaving several aspects of the AT into an interesting and informative piece. Well done Xpress!

Good observations! Lots better than many articles written about the AT.

Hike on!

Scribbles

GAME ’11