Maryanne Vollers: “You can’t read this guy’s mind,” she says of Rudolph — but her investigation turned up signs of what drove the serial bomber.

|

Western North Carolina’s most notorious terrorist may be submerged in solitary confinement in a “supermax” penitentiary, but that didn’t stop Eric Rudolph from making the national news again recently.

In a Dec. 10 article, the Colorado Springs Gazette reported on a year’s worth of sporadic correspondence between the newspaper and Rudolph, the former WNC resident who now spends 23 hours a day in a 7-by-12-foot cell in Florence, Colo. The story proved that Rudolph remains a man with a mission — and that his message remains the same one his bombs sent.

|

In his letters, Rudolph showed no remorse for his bombing spree, which killed two people while injuring and disfiguring scores of others. He shared a sneering, 16-page work of “satire,” as he called it, that mocked not only the federal government’s prosecution of him but also — in strikingly snide terms — some of his victims.

Rudolph further maintained that the conditions in the federal prison where he lives along with a handful of other men judged the most dangerous in the United States — including “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski — are purposefully calculated to drive the inmates mad. “Supermax is designed to inflict as much misery and pain as is constitutionally permissible,” Rudolph wrote.

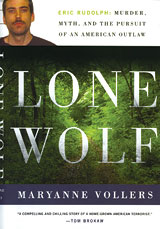

If there’s one person in the world (besides the man himself) who’s best suited for deconstructing Eric Rudolph’s communications and rationalizations, it may well be journalist/historian Maryanne Vollers, who’s spent years trying to get inside the criminal’s mind and to flesh out the stories of the people who chased him during his five years as a federal fugitive. Her new book, Lone Wolf: Eric Rudolph — Murder, Myth, and the Pursuit of an American Outlaw (HarperCollins, 2006), offers an illuminating account of the bomber’s exploits while he was on the lam.

The federal government burned through $20 million and countless other resources while trying to track Rudolph down within a relatively small area. His behavior during that time raises many lingering questions. Where was he? How did he survive and elude detection? And, perhaps most importantly, how did he reconcile a life in hiding with the life of violent action he was still drawn to?

Vollers, an investigative reporter and editor who wrote the acclaimed book Ghosts of Mississippi: The Murder of Medgar Evers, the Trials of Byron De La Beckwith, and the Haunting of the New South (Little, Brown & Co., 1995), launched her quest to answer those and many other questions mere weeks after Rudolph was arrested in 2003. Surprisingly — Vollers still doesn’t know why — the former fugitive agreed to address many of her queries via mail, even as he largely brushed off inquiries from other journalists.

With this rare correspondence, as well as dozens of interviews with other key players in the Rudolph case and extensive documentary research, Vollers adds new information at every turn. Asheville readers will note that their city was on Rudolph’s radar during his time in hiding. He built a bomb to destroy a local abortion clinic and would have delivered it on Halloween weekend in 2000, if the truck he stole to get it here hadn’t failed a short distance from Murphy. (Asheville was also the source of Rudolph’s most potent explosives, Vollers notes: He stole some 340 pounds of dynamite from the Austin Powder Company here in December 1996.)

Vollers unearths a great deal about Rudolph’s strategy and tactics, breaking new ground in her attempts to penetrate his mindset. In the process, she paints Rudolph as a more complex character than many observers might assume he is.

Depending on whom you ask and which evidence you focus on, Rudolph was driven by some amalgam of racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia and archfundamentalist “Christian Identity” beliefs. Lately, he’s said that abortion clinics were his most important targets, because they represent the “decline of Western civilization” that he says he’s fighting against.

“Abortion is murder,” Rudolph wrote in a manifesto released when he pleaded guilty to the bombings in April 2005. “Because this government is committed to maintaining the policy of abortion, the agents of this government are the agents of mass murder, whether knowingly or unknowingly.” That, Rudolph noted, is why he set off his bombs — to kill federal agents who protect a practice he deems murderous.

That explanation didn’t exactly square with Vollers, though, and she seems resigned to the fact that we still know only some of what makes Rudolph tick. “You can’t read this guy’s mind,” she observes.

At the same time, however, “I was able to get at least a glimpse into this peculiar and frightening mind,” Vollers asserts. “He’s a very bright man, and coldly sane. A lot of people think these bombers have to be madmen, but he’s not insane at all — he’s deeply disturbed but frighteningly logical.”

Xpress interviewed Vollers by phone from her home in a small Montana town; here are excerpts of that conversation.

Mountain Xpress: Eric Rudolph was back in the news this week, having corresponded with the Colorado Springs Gazette.

Maryanne Vollers: Right — so I can no longer claim to be the only journalist he’s written to.

MX: I was struck by this “satire” he sent them. I wondered if it seemed out of character to you — the amount of vitriol there — or was it classic Rudolph? I ask the questions because your correspondence with him seemed a little more fact-based and earnest.

MV: To me, it’s classic Rudolph. He has a very sarcastic, cruel side to him. … He can be pretty funny, but it’s always in a cutting way. What he wrote is vicious — there’s no other way of putting it. Some of it is mildly amusing, but what he’s doing is lashing out from prison at his victims, and that’s just unconscionable.

There are two things going on, as far as I can see. One is that his complaints about what’s happening in the prison are valid. There’s a real problem there. My feeling is that we send people to prison as punishment — we don’t send them there for punishment. That’s what the barbaric countries do.

But obviously he’s been also getting this other track out about his victims and his sentencing. And the thing is, he’s a good writer. … He can construct a very good story.

MX: At the same time, Rudolph has been extremely selective about who he communicates with from the media. Why do you think he’s been relatively responsive with you?

MV: I never did find out why. I have my theories, which I write [about] in the book. … I think he’s very aware of his position in history and wants to be understood for who he thinks he is.

MX: Do you feel like, in the end, you’ve determined what really drove him?

MV: Nope. I don’t pretend to have the answers. The human heart is an endless mystery, and I don’t think he knows why he’s done what he’s done.

I asked him himself, and he didn’t have a really good answer. To him, there was a “tipping point” — a buildup of frustration against what he perceived to be an immoral and illegal government that condoned abortion.

I believe that, more likely, it’s a psychological factor: He’s a true believer in a cause because he’s unable to connect with other people.

MX: Especially since his sentencing, Rudolph has said he did it all in opposition to abortion. But has he had to answer questions about why he bombed both a gay club and an Olympic site in Atlanta if abortion was his motivator?

MV: Here’s the way Rudolph thinks, as far as I can tell from his answers to me. It makes perfect sense to him — each of [those targets] represents a different phase in “the decline of Western civilization” [as Rudolph puts it], which is what he’s defending as a soldier in the army of his own making. The Olympics represented egalitarianism, tolerance and commercialism — he’d put all these things together. … Plus, it was a way to draw in federal agents to their death. [Rudolph had planned to set off a total of seven bombs in Atlanta, he later claimed, most of them targeting federal law enforcement.] Abortion clinics and gay establishments are going to have a federal response when they get bombed, and the secondary devices [additional bombs Rudolph left] were there to kill them.

MX: What did you learn about Rudolph that most surprised you?

MV: You don’t usually find a serial killer with a sense of humor. You see a vicious aspect of it in this “satire” he wrote. … I was surprised that he made friends with his African-American jailer; I was surprised that he befriended his Jewish lawyer. … Even Rudolph had some humanity in him that people could locate.

MX: As an author who’s trying to probe the mind of a subject who’s done such detestable things — but someone you’re really trying to understand — did sympathies arise that surprised you?

MV: You can’t help but wonder what he might have become if his father hadn’t died [when Rudolph was] 12, and if he hadn’t come under the wing of a white-separatist, Christian Identity believer. With all [Rudolph’s] talents and capacity, maybe something in there could have been saved. Sympathy isn’t the word, but you can empathize with any human being — at least I can. You know, even the worst of us, there is always something there. But I could never get past what he did.

MX: What key questions do you still have about Rudolph that you weren’t able to find answers to?

MV: I want to find out more about the bombings themselves; he never wanted to discuss them. What kind of surveillance he did, that kind of question of fact. …

There are some missing years here. I just got a review that said, ‘We wish she’d written more about what he did in the woods.’ Well, I wish he’d told me more [about that], because I would have written every last thing he told me. I’m not satisfied that we know exactly what he did.

MX: Stepping back a bit from his case, how much has Rudolph served as a sort of folk hero or guiding light for the radical right?

MV: I guess it remains to be seen. … He seems to be reaching out now to get a following. ‘Thank God he’s an introvert!’ is what a lot of people said when he was in the woods. If he had been sending out missives when he was in hiding, he’d be a huge folk hero, don’t you think? But he didn’t, because of his psychological problems. He can’t figure out how to connect to people, and we should all be grateful for that.

What a complicated man. He had every opportunity to turn himself into the Jesse James of the anti-abortion movement, and he just didn’t do it, thank God.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.