UPDATE (July 8, 2015): North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services announced on June 30 that the state will be the recipient of a $7.8 million federal grant.

The grant was awarded by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to facilitate and expand recovery options and treatment for substance abuse disorders, according to an official press release from DHHS.

Grant money will be applied specifically towards programs and treatment which aids homeless populations, individuals recently released from jail or prison, and pregnant and new mothers working to kick substance dependency.

The money will help state and local agencies provide services to recovering addicts ranging from basic medical and dental care to housing assistance, parenting classes and education opportunities, says Rose Hoban in an article for NC Health News.

For recovering addicts seeking help in piecing their life back together, there’s a framework in place to help facilitate a smooth recovery, says Terri Conyers, service director at Recovery Communities of North Carolina, in an interview with NC Health News. “We sit down and make a plan for their recovery, what are thee goals you’d like to attain, what are your largest barriers at this moment.”

Organizations like Recovery Communities will then follow and track a client’s progress on the path to recovery and provide support and resources as needed.

This news comes in the midst of an innovative effort by Smoky Mountain LME/MCO to install an integrated care system in western North Carolina that would streamline communication between public and private care providers across disciplines around the region.

The new system would make it easier for those dealing with substance abuse disorders or mental health issues to receive on-site, comprehensive care and treatment. Implementation of this program is currently underway; in May 2015, Smoky Mountain hired Peter Rives as director of the integrated care initiative. Rives has worked within the mental health field for over 15 years and has conducted substantial doctoral work in the field while at the University of Delaware.

Stay tuned for more info on integrated care initiatives in WNC and updates related to substance abuse treatment.

********

Amid escalating use and abuse of opioids nationwide, the number of local narcotics-related overdoses has increased rapidly in recent years. The drug naloxone can temporarily suspend those drugs’ effects, and the Asheville metropolitan area leads the state in confirmed cases of opioid overdose reversal, according to the N.C. Harm Reduction Coalition.

But that’s largely a function of how naloxone is distributed here rather than a sign that the area has more opioid abusers, notes Tessie Castillo, advocacy and communications coordinator for the Durham-based nonprofit.

Meanwhile, tougher restrictions on prescribing pharmaceuticals have led more and more local addicts to turn to an illegal opioid: heroin. The Asheville Police Department is “seeing a correlation between lower pill seizure rates and higher heroin seizures,” reports Public Information Officer Christina Hallingse. In the last four years, the APD has seen the total number of heroin seizures jump from 0 to 28 per year.

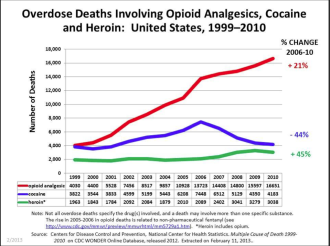

Local overdose rates peaked in the mid-2000s and have remained somewhat stable since then. Between 1999 and 2013, however, Buncombe County had 252 opiate-related deaths, the N.C. Injury & Violence Prevention Branch reports. It’s hard to pinpoint how many of those were due to opioids, notes Dr. Craig Martin, chief medical officer at the Smoky Mountain Local Management Entity/Managed Care Organization (LME/MCO). But statewide, opioids are now involved in more drug deaths than cocaine and heroin combined, according to statistics from the state Department of Health and Human Service’s Injury and Violence Prevention Branch.

And though the overall numbers may be small, the impact on human lives is considerable. Local health professionals say they’re seeing more children and early teens abuse drugs, and inadequate funding limits treatment options.

“The finances of trying to get suitable help are ridiculous,” says Terrence Streeter, program director for Next Step Recovery in Asheville. “It gets to where it’s almost like no one is paying attention to what’s really happening: People are dying.”

Diagnosing dependency

Prescribed by a physician, legal opioids such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine and codeine help patients deal with post-surgical discomfort or chronic conditions. The term also includes such illicit narcotics as heroin and opium. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, opioids “reduce the intensity of pain signals reaching the brain and affect those brain areas controlling emotion, which diminishes the effects of a painful stimulus.”

Not surprisingly, then, legal opioids are in widespread use. Between 1999 and 2010, sales of opioid pain relievers quadrupled nationwide, according to a 2013 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But these drugs’ powerful effects also make them prime candidates for recreational use, sparking a marked increase in overdoses.

Nationally, “Medical emergencies related to nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals increased 132 percent in the period from 2004 to 2011,” a 2013 report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration noted. This included “a 183 percent increase in the involvement of drugs classified as opiates/opioids.”

“Addiction is a disease,” says Brian Goodlett, program director for the Asheville-based Western Carolina Treatment Center. “Like any other chronic disease, it has its origins in both genetics and lifestyle. Family history plays a large role, as does medical history and mental health.”

Meanwhile, the age when individuals begin using drugs is dropping, says Streeter. “We accept people starting at 18, but these guys are starting when they’re 13 and 14 years old.”

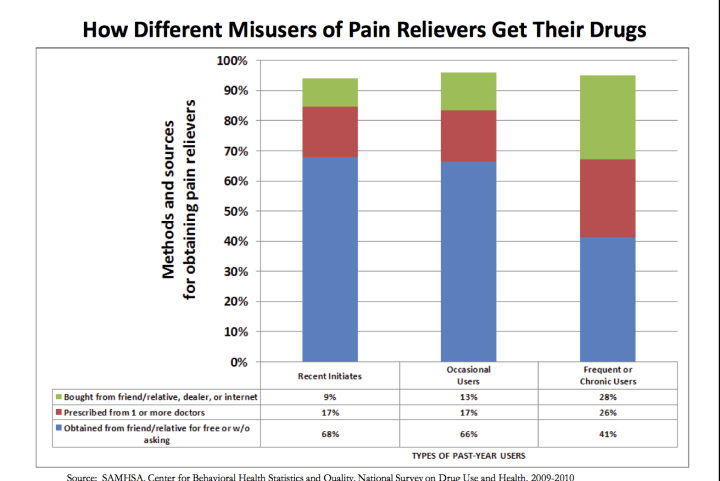

Many users turn to opioids to manage other problems, Castillo explains. “They may have trouble with depression or anxiety or other mental health disorders and use opiates to self-medicate.” The ready access to powerful prescription drugs in family medicine cabinets also contributes to opioid abuse.

Unintentional poisoning

In 2012 alone, 673 North Carolina deaths were reportedly linked to “unintentional poisoning by opioids,” not counting opium and heroin, according to a 2014 Policy Review by the North Carolina Medical Board. Dr. Chris Flanders, medical director of Mission Hospital’s emergency department, says he’s seen a steady rise in overdoses during his 13 years at Mission — and an “explosion” of narcotics-related cases since 2010.

The hospital, says Flanders, has “done quite a bit of work trying to prevent the inappropriate prescribing of narcotics from the ER.” But balancing that concern against the need to treat patients’ pain can be difficult, he continues, noting, “It’s not necessarily obvious that there is an abuse issue.”

Patients requesting pain medication have their prescription history checked through the North Carolina controlled substances database, he explains. “We try to limit the amount of pain pills we prescribe to any one individual. If we see that they had 100 Percocet prescribed the day before, then we’re not going to be able to give them any pain medicine.”

This has helped get these pills off the street, but in response, many addicts are turning to an older, cheaper alternative. “Over the last two years, we’ve seen cases of heroin addiction on the rise,” Goodlett reports.

A deluge of cheap heroin from Mexico is also helping drive the shift from pharmaceuticals to needles, notes Hallingse, the APD’s spokesperson.

Streeter, meanwhile, recalls one patient “who had never done [drugs] before but ended up in a car accident.” He was given a prescription for opioids, became addicted and wound up turning to illegal narcotics when he no longer had access to the pills.

“That story seems to be the norm now,” says Streeter. “It’s getting to where either they die or they commit to recovery.”

In addition to the direct risks of opioid use, sharing syringes to inject heroin has amplified the risks of contracting bloodborne diseases like hepatitis C and HIV, Goodlett points out.

Back from the brink

When a suspected opioid overdose case comes through the doors at Mission, says Flanders, “The primary danger … is that it suppresses the respiratory drive in your brainstem, so the first step is to aid the patient’s breathing.”

Step two is usually administering naloxone, which replaces opioids in the brain’s natural receptors and can temporarily snap the patient back into consciousness.

Passage of the state’s 911 Good Samaritan Law in 2013 paved the way for a considerable expansion of the Harm Reduction Coalition’s work. The law protects those prescribing, distributing or administering naloxone from prosecution, as well as people experiencing a drug overdose and those trying to help them.

Since 2013, when the nonprofit began distributing naloxone statewide, it has confirmed 586 overdose reversals. The Asheville metropolitan area tops the list, with 156 cases to date.

“In Asheville, we distribute very differently than in other areas of the state,” Castillo explains, because treatment centers here have been more willing to take part in the program. That makes it easier to track the local success rate when patients return for repeat visits.

Goodlett has high praise for Castillo’s organization. “I really can’t say enough good things about the Harm Reduction Coalition and the work they do,” he says. “They’ve had a big impact in our state’s efforts to treat substance dependency.”

Naloxone kits are “becoming more prevalent around the community,” says Streeter, who carries one with him at all times. “It’s registered with the state,” he notes, “so if I use it, I have to call and give them the number of the packet I used.” To date, he hasn’t had to administer the drug, but many colleagues have used it successfully.

Naloxone is also catching on elsewhere in North Carolina. In Fayetteville, more than 200 police officers have been equipped with the life-saving drug, and in April, the Durham County Detention Facility became the first jail in the South to give it to recently released inmates. In the first two weeks after release, they’re over 100 times more likely to die of a drug overdose than the general population, according to the Harm Reduction Coalition.

As recently as a few years ago, notes Castillo, treatment centers and law enforcement alike opposed widespread distribution of naloxone. “We were often accused of facilitating more drug use,” she reports, “which is very incorrect.”

Flanders concurs. “Frequently people are not very happy when they wake up: Not only have you taken away the buzz, but now they’re in complete narcotic withdrawal.”

And while naloxone saves lives, it can still leave addicts at risk. “The half life of naloxone isn’t as long as the half life of the narcotics in their system,” he explains, “so once the naloxone wears off, they can be back in an overdose state.”

Road to recovery

There are four publicly funded local treatment programs (see box, “Finding Help”).

Many patients seeking to kick their addiction, however, turn to private facilities, which typically offer intensive programs including both inpatient and outpatient therapy.

Streeter, a former addict, credits the program he now works for with helping him assess his life honestly. “I took the time I needed to focus on myself,” he reveals. “It had reached a point where I was so eager to please everyone else. I took this time to figure out what made Terry click.”

The residential program at the Julian F. Keith Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Center in Black Mountain, where Streeter stayed for a period of time, gave him a stable place to be that was free from old temptations — a huge help. The program also provides food and transportation to support groups like Narcotics Anonymous, which he still attends weekly.

“There’s not a magic pill or potion,” adds Streeter. “It takes commitment, and it takes reaching out and asking for help, letting others love you.”

Goodlett agrees, adding that the stigma attached to drug abuse compounds the problem. “There’s still a lot of work to be done in terms of educating the public on what these people are going through and how challenging that process is.”

Groups like the Harm Reduction Coalition, notes Castillo, must also overcome addicts’ fear of exposure. “It’s very difficult to work with active drug users,” she says, because opioid abusers operate in a clandestine subculture, and it typically takes a long time to build trust.

In addition, says Streeter, “It feels like nobody cares sometimes, and people lose hope and go right back to doing what they did before. It only takes a minute to change your mind: There’s only a small window available before it’s too late.”

Financial hurdles

Inadequate funding and limited space in treatment facilities further complicate the situation for patients and care providers alike. In the past few years, Flanders reports, the state Legislature has slashed funding for mental health resources by almost 90 percent, sharply reducing public care providers’ ability to treat substance abuse.

And as state funding continues to decline, Martin of the Smoky Mountain LME/MCO says he’d like to see a shift toward the comprehensive care treatment model, in which Medicare dollars supplement shortfalls in state support.

Castillo says her organization “receives no state or federal funding,” instead relying mostly on private donations. There is no federal money for harm reduction programs, she explains, and there’s actually a ban on funding needle exchanges. In Northern states, state and local governments often fund harm reduction programs, but in the South, it’s typically up to foundations and private donors to support such efforts.

Health insurance provides only limited help. Treatment centers, notes Streeter, often don’t accept it, and insurance plans may not cover this kind of treatment. In addition, many addicts lack health insurance.

At the Western Carolina Treatment Center, patients pay 100 percent of the costs, says Goodlett. But while these programs may seem expensive, it’s no more than what drug users spend to support a habit, he points out. And though he declined to specify how many patients his agency sees in a given year, Goodlett says, “There is no shortage of business.”

Meanwhile, for patients whose first attempt to get clean fails, there are even fewer options. “I deal with guys that will relapse after the program, and it’s like pulling teeth to try and get them help,” says Streeter. “We don’t really want to dismiss them from the program, but what do we do?”

The Smoky Mountain LME/MCO, notes Martin, tries to consider “whether people are being helped toward recovery or are being provided the same thing without getting better. It’s not so much that we say this patient doesn’t need treatment, but perhaps they need a higher level of care than that particular program can provide.”

Hopeful signs

Despite the many challenges, however, there are positive signs.

A new state-funded comprehensive care center offering mental health and addiction treatment will open at 356 Biltmore Ave. later this year. The 16-bed, 24-hour, urgent care and crisis facility will offer a wide range of services, with financial support from both Buncombe County and Mission Hospital.

Meanwhile, growing acceptance of basic treatment options like naloxone is making a difference, says Castillo. “We see a lot of positive steps in the right direction. Just a couple of years ago, no methadone clinic would let us in; now, they are practically begging us to come.”

For his part, Streeter believes addiction should be “viewed as a credible disease” rather than a crime. “I would love to see it easier for a person to receive treatment services than go to jail for doing things that happen naturally in addiction.”

In the meantime, though, he says he’ll continue giving others the same kind of help and attention he received. “That’s one of the reasons I’m here now: to let people know there’s a way out of this, and you don’t have to keep going back to the same thing.”

Finding help

At RHA Health Services and Family Preservation Services in Asheville, patients on Medicaid and those without insurance can receive same-day care and outpatient treatment for opioid addiction. Black Mountain’s Julian F. Keith Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Center provides inpatient care. And the Mountain Area Recovery Center accepts Medicaid payments and provides outpatient treatment at its Asheville and Clyde facilities. The Smoky Mountain LME/MCO’s toll-free, bilingual, 24/7 hotline (800-849-6127) assists WNC residents without insurance in finding help.

A good article. Having worked in SA treatment for three years, I must add the following to the criticism that “there’s actually a ban on funding needle exchanges”. This is not just because it implies that the State believes that IV drug users are going to use anyway and may as well do so sanitarily (although this is part of their resistance).

The provision of clean needles DOES NOT prevent HIV and Hepatitis, because most drug abusers are NOT shy loners shooting up alone in dark, isolated corners. Drug abuse is a shared, social activity. IV drug abusers typically pair up to use together, diluting their narcotics with blood from one user’s vein before re-infusing half of the mixture back into the first user’s vein, and the other half INTO THE SECOND USER’s vein. No matter how clean the needle is, the second user is receiving the blood of the first user. Would YOU trust your drug-abusing partner not to have Hepatitis or HIV?

Thanks for pointing this out, Al. That’s a very good point, and you’re correct: most users are not using alone, and sharing needles between injections is a very common practice. In addition to the issue of diluting with blood, many needle users also use the same “filter” (often the end of a cotton swab or something similar) for multiple injections, opening that second user not only to blood-borne viruses, but bacterial infections such as cotton fever, which is an extremely unpleasant experience.

Perhaps more emphasis should be put on “clean works” practices when addressing active users, though I can’t speak to how much of that education actually goes on. Thanks for addressing this issue, and for your work with substance abuse!

A quick follow-up on the topic of needle exchange programs. A couple recent studies have been brought to my attention concerning the effectiveness of such programs, that I believe are worth sharing, since Big Al brought the topic up. This study by the World Health Organization highlights exchange programs as one strategy for the prevention of spreading HIV among intravenous drug users, among others:

http://www.unodc.org/documents/balticstates/Library/NSP/EffectivenessNSP.pdf

Another document, issued by the US Surgeon General in 2011, recommends exchange programs as “effective in reducing drug abuse and the risk of infection,” and cites several studies as the basis for this recommendation. That can be found here:

https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2011/02/23/2011-3990/determination-that-a-demonstration-needle-exchange-program-would-be-effective-in-reducing-drug-abuse

Overall, I think needle exchange is an important tool in preventing the spread of blood-borne viruses and diseases, but is certainly not the only step towards prevention that can and should be taken.

It seems pointless to generalize about the habits of all drug users–perhaps there are some who share needles as you say–there are many others, to be sure, who would benefit immensely from clean needles. This seems like a no-brainer to me. Needle exchange programs cost very little, but they save lives for the users who avoid HIV and Hep C. Not to mention, all of our health care costs come down when there are less emergency room visits–particularly by the uninsured. Clean needles will keep some citizens out of urgent care.

The whole point of syringe exchange is to get people enough new syringes and new equipment for each injection. If people do not share equipment or syringes there is no disease transmission. If people are forced to share syringes and equipment, due to a lack of access (like for the most part everywhere in NC), they will. If they don’t have to, they won’t. That is why syringe exchange is supported by every major scientific body as the most effective form of HIV and hepatitis prevention.

Law enforcement officers are particularly at risk for HIV and viral hepatitis transmission. In one study, 1 in 3 officers reported being stuck by a syringe during their career, and 28% reported receiving more than one stick, most commonly during pat-downs and searches. Considering the frequent contact between Injectors and law enforcement, officers should be aware of potential dangers and know how to protect themselves, their fellow officers and the public from the further spread of these illnesses Empirical data has shown that one of the most effective ways to reduce the incidence of needlestick injuries to law enforcement, as well as to reduce the spread of HIV and viral hepatitis, is to amend state laws that restrict public access to syringes. While it may seem counter-intuitive, allowing people access to syringes, whether for diabetic insulin or drug injection, is proven not only to reduce needlestick injuries to law enforcement and to curb the spread of blood borne disease, but is also shown to reduce crime and drug use in areas where such laws have been enacted.

Great, you just made life even more difficult for anyone with diabetes by making needles more difficult for them.

“People are dying” — nobody cares about dying addicts. Addicts cause crime, steal, are homeless, are a burden on law enforcement and are a tax burden. Nobody cares. A dead addict means the neighborhood is that much cleaner and safer.

I think Mr. Childs said the opposite actually, Diabetic. Needle exchange makes it easier for diabetics to access needles for their needs too, because intravenous drug users don’t have to constantly claim they’re diabetic at pharmacies to access clean needles.

Thank you for trolling, however.

Thank you Mr. Childs. I agree, after reviewing the scientific literature it clearly supports the efficacy of needle exchange programs.

NCHRC just found out about 2 more naloxone overdose reversals in Asheville, making it 160 reversals in Asheville.

Diabetic, I am sorry you feel that way. My husband is a diabetic and I am not worried about him getting needles, but the minute you say no one cares about addicts and a dead addict means the neighborhood is safer and cleaner is where I have to stop you. My son died in Asheville. Yes he was an addict and yes my son did try to kick the habit but relasped. My son was put on a very strong pain medication when he was a senior in high school due to a major surgery. He was 18 and the doctor did not need my permission to give him refills (which I did not know at that time) and he kept refilling the prescriptions because my son thought he was really hurting, but in fact he had become addicted. My son died on November 22nd, 2013 and I miss him everyday. He was sold a poisoned drug which killed him immediately. When you have a child die from this disease then come back and comment about how your neighborhood is much cleaner now.

I liked Harm Reduction Coalition because HIV is a bad way to go, worse even than old age. But opiate overdose is such a good way to go that I keep wondering why they don’t use siezed heroine for the death penalty; perhaps it wouldn’t be deterrent enough. Anyway, this huge difference in suffering between HIV and overdose makes needle exchange far superior to naloxone.

I have a bone spur in my hip and degenerating disc in my lower back and congratulations I cant sleep at nite because of the pain and getting up out of a chair is nearly impossible but I have a business I have to work 6 days a week constantly in pain and most of the time without sleep since the system is tightening up the doctors have turned into little girls afraid to give me anything for the pain so what am I to do turn to heroine ? it looks like it may be my only option I see other people getting this medication some that don’t even need it and that really isn’t right if a person that genuinely needs the medication but cant get it why is the medication allowed why isn’t it outlawed completely someone enlighten me and explain please if my blood pressure is high I am encouraged to start on blood pressure medication and after you start taking that you usually have to keep taking it or if you stop your blood pressure skyrockets and you die that’s a form of addiction also because you have to take it I am a business owner that is constantly in pain and needs this medication just as there is others out there in the same boat that suffer every day